In Civilized Shamans: Buddhism in Tibetan Societies, Geoffrey Samuel offers a sweeping anthropology of Tibetan religion that refuses to take Tibetan Buddhism at face value. He finds a living tradition shaped by older and more unruly forces beneath the polished scholastic surface of the monasteries. What emerges is a civilization of monks and magicians, of disciplined philosophers and ecstatic ritualists. His argument is simple but radical: Tibetan Buddhism is the result of Indian Buddhist ethics and philosophy meeting the shamanic substratum of the high plateau.¹

Two orientations: clerical and shamanic

Samuel organizes Tibetan religion around two poles. The first, the clerical or monastic orientation, descends from Indian Buddhism with its monasteries, ethical codes, and scholastic systems of thought. It values restraint, karmic causality, and the gradual cultivation of enlightenment. The second, the shamanic orientation, grows from indigenous Tibetan practices centered on ritual efficacy, spirit interaction, and the manipulation of unseen forces. This orientation values power (dbang) more than purity and treats ritual specialists not as moral exemplars but as technicians of spiritual power.²

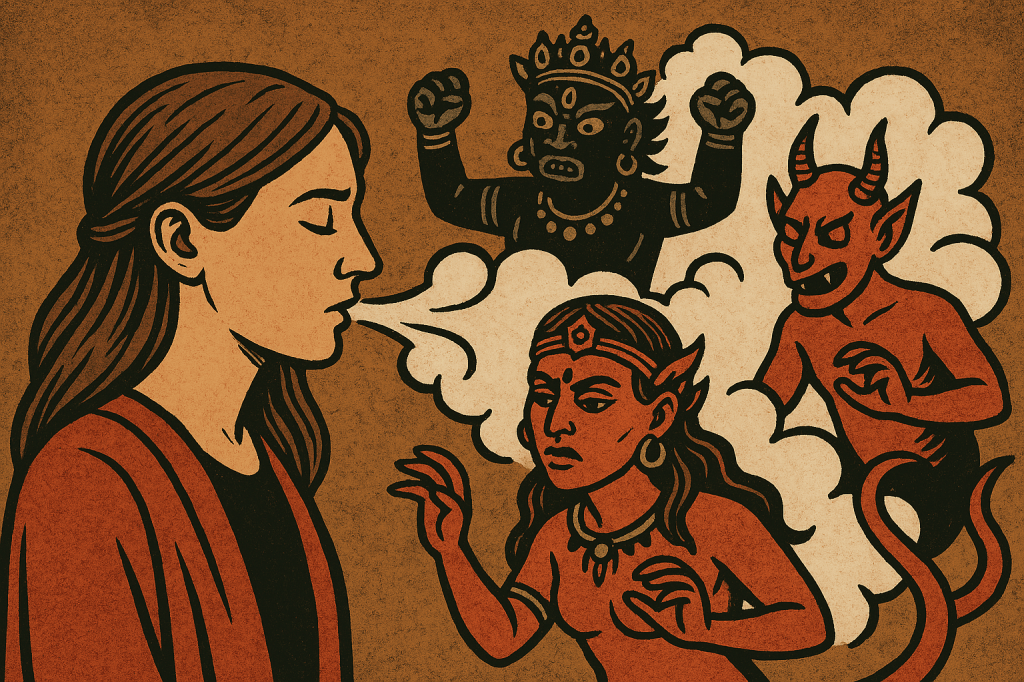

These two strands were never simply reconciled. Tibetan civilization attempted to domesticate the shaman. The ecstatic healer and spirit-fighter was refashioned into a lama, wrapped in robes and scriptures yet still capable of commanding spirits, averting misfortune, or destroying an enemy through ritual means. The civilized shaman is not a metaphor. It is a social type, the institutionalized magician of a literate Buddhist society.³

Dark rituals and the question of subjugation

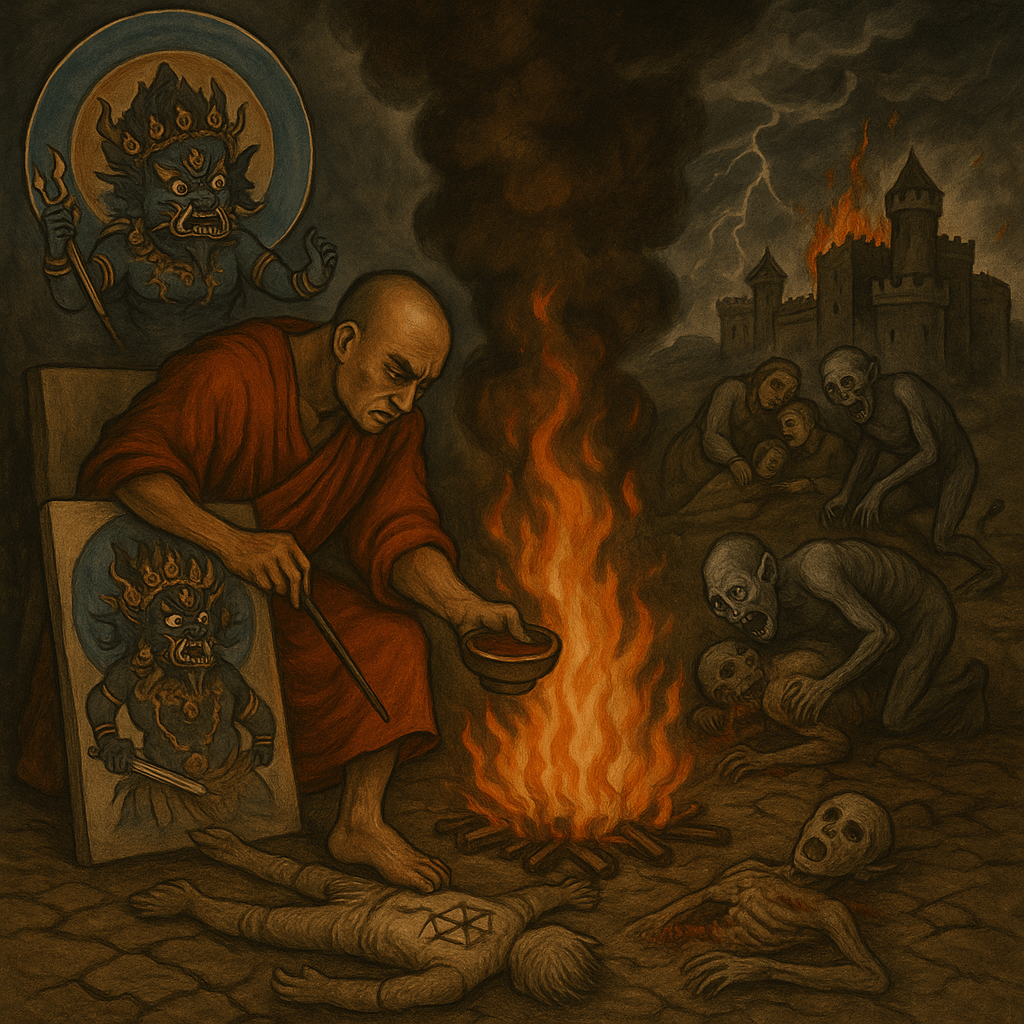

The most uncomfortable continuity between these worlds lies in the domain of ritual violence, what Tibetan sources call drag-po or wrathful rites. These practices are directed not toward enlightenment but toward control: the binding, subduing, or annihilation of obstructing forces, whether demonic, psychic, or human.⁴

Samuel interprets these rites not as moral aberrations but as necessary expressions of the shamanic orientation within a Buddhist frame. Indian Buddhism had long flirted with magical power but kept it at the margins of monastic life. In Tibet, ritual mastery became central. The same lama who taught compassion might also perform a subjugation rite, using effigies, mantras, and visualizations of wrathful deities to annihilate obstacles, whether spiritual or human. Such practices, found in the Nyingma and Kagyu tantric cycles and institutionalized in monastic ritual manuals, embody a logic foreign to classical Indian soteriology yet native to shamanic cosmology, the idea that power must be met with power.⁵

What makes these rites “civilized” is not their ethical domestication but their integration into a bureaucratic religion. The Tibetan monastery became a regulated arena for managing violence and transforming it into ritual performance. The monastic code that forbade killing also licensed symbolic destruction: paper effigies burned, dough figures pierced, and demons tamed through mantras.⁶ This was how a society of monks could still believe in, and even engage in, acts of ritual aggression.

Power and legitimacy

Samuel’s analysis is more about social structure than theology. The clerical orientation secured legitimacy through moral authority and learning, while the shamanic orientation maintained relevance through immediate and pragmatic results. The former built monasteries; the latter kept communities going amid famine, disease, and invasion. Tibetan Buddhism’s durability, he argues, comes from this uneasy synthesis. The scholar-monk and the ritual adept needed each other: the first to lend doctrine and order, the second to command the spirits that haunted every valley and household.⁷

In this light, the dark rituals of subjugation are not aberrations but instruments of governance. They discipline the chaotic powers of the landscape just as the monastery disciplines the passions of the mind. To them, the wrathful deity is not a contradiction of compassion but its shadow: compassion armed.

Rethinking the “Buddhist” in Tibetan Buddhism

Samuel’s greatest contribution may be to unsettle what we think “Buddhist” means. By treating Tibetan religion as a field of interacting orientations rather than a single orthodoxy, he exposes the limits of modern, idealized Buddhism. The vision of Tibet as a purely pacific, philosophical culture depends on forgetting the tantric rites that promise to destroy human enemies or subjugate spirits.⁸ Samuel does not moralize about this tension; he historicizes it. The so-called civilized shaman is a figure born of necessity, mediating between an imported moral system and an indigenous world of volatile gods.⁹

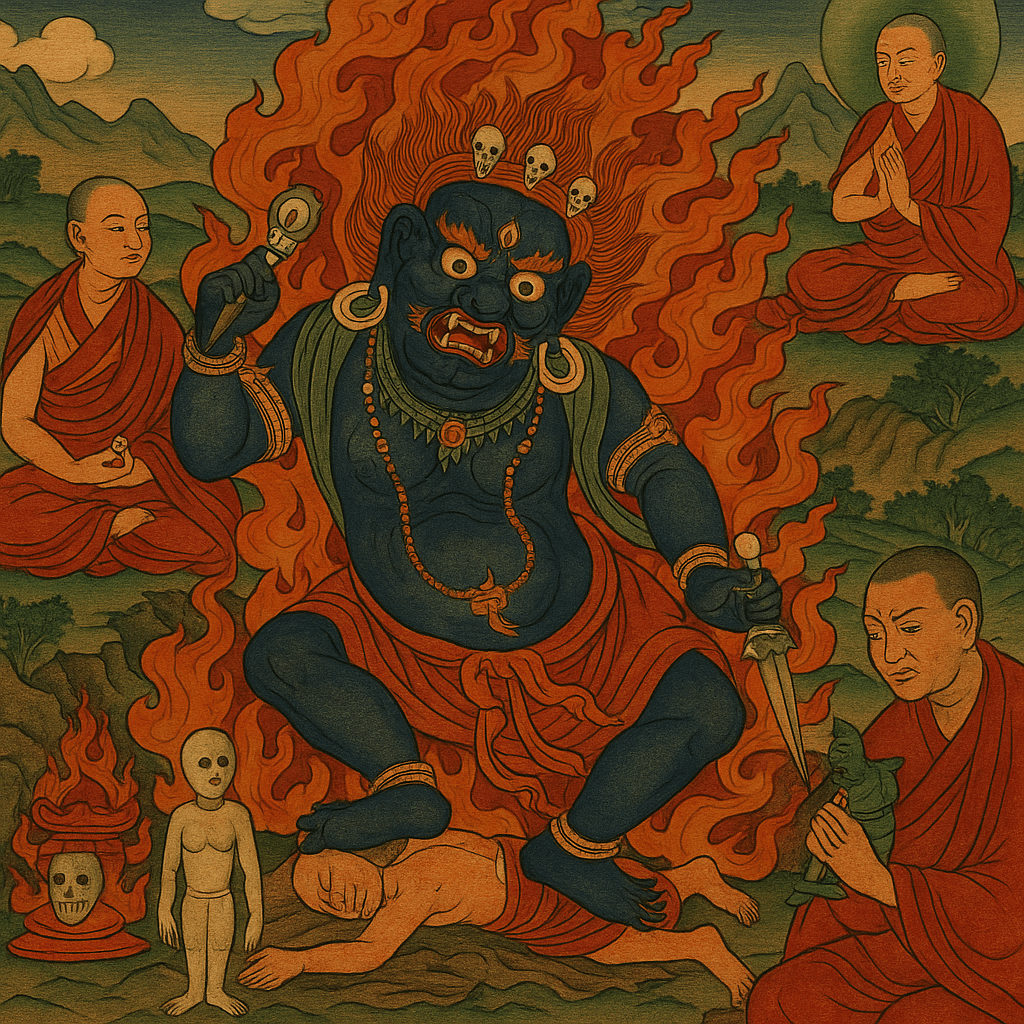

A note on tantra as the mediating field

Samuel does not treat Hindu tantra as a third, independent strand within Tibetan Buddhism. Rather, he presents tantric practice as the meeting ground of the clerical and shamanic orientations. By the time tantra reached Tibet, Indian Buddhism had already absorbed many Śaiva and Śākta elements. What Tibet inherited, therefore, was a fully developed tantric Buddhism rather than a simple blend of Buddhist and Hindu ideas. In Samuel’s account, tantra provided the channel through which shamanic power could operate within a clerical framework. It was the mechanism that allowed ecstatic and ritual techniques to coexist with the disciplines of monastic scholarship.

He also describes tantric Buddhism in Tibet as a two-way exchange. The imported Indian systems of Hevajra, Guhyasamāja, Cakrasaṃvara, and others were reinterpreted through local cosmologies of mountain gods, territorial spirits, and ancestral deities. The result was what he calls “tantricized shamanism” or “shamanized Buddhism.” While Hindu tantra was one historical source, the Tibetan tantric complex became a hybrid formation that expressed shamanic cosmology through Buddhist doctrine.¹⁰

The afterlife of the civilized shaman

Civilized Shamans was published in 1993, before the wave of globalized Tibetan Buddhism tried to reframe lamas as psychologists or humanitarians. Yet its insight remains vital. Beneath every system of enlightenment lies a system of control. The Tibetan synthesis worked precisely because it did not abolish the shamanic element. It incorporated it, turning ecstatic violence into liturgy and spirit warfare into cosmology.¹¹

For those interested in understanding tantric practice, especially the darker currents of subjugation and protection, Samuel’s anthropology is a cautionary mirror. It reminds us that ritual power is never purely symbolic. Even when intellectualized, it retains the logic of coercion: to bind, to summon, to annihilate. Tibet’s civilization was built on mastering such forces. The tension Samuel describes is not an accident of history but a model of how Tibetan religion evolved. Civilized shamans appear wherever doctrine meets magic, wherever ethics must coexist with power. Tibet made that paradox explicit.¹²

Notes

- Geoffrey Samuel, Civilized Shamans: Buddhism in Tibetan Societies (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993), 11–13.

- Samuel, Civilized Shamans, 11–12, 134–136.

- Ibid., 478–480.

- Ibid., 238–240.

- Ibid., 259–262.

- Ibid., 468–471.

- Ibid., 465–469.

- Ibid., 244–246, 478.

- Ibid., 479–482.

- Ibid., 66–74, 242–243, 476–478, 480–481.

- Ibid., 476–479.

- Ibid., 481–482.