In Vajrayana Buddhism and related tantric systems, practitioners are taught that enlightened activity manifests in four fundamental modes, often called the Four Activities. These are commonly translated as Pacifying, Enriching, Magnetizing, and Subjugating. In Sanskrit they correspond to śāntika, pauṣṭika, vaśīkaraṇa, and abhicāra. In Tibetan sources they are known as zhi, rgyas, dbang, and drag po.

Doctrinally, the Four Activities are described as spontaneous expressions of awakened compassion. An enlightened being pacifies obstacles, enriches virtue and resources, magnetizes beings toward the Dharma, and subjugates harmful forces. This presentation emphasizes intent and realization, assuring the student that such actions, when performed from enlightenment, are free of karmic stain.

Yet this sanitized description obscures a more uncomfortable reality. Historically and textually, the Four Activities function as classificatory frameworks for large compendiums of ritual technologies. These include magical spells, rites, visualizations, mantras, and talismanic operations designed to bring about very specific effects in the world. Such effects include healing and calming, increasing wealth or longevity, attracting and binding others, and coercing, harming, or destroying enemies.

This dual framing creates a tension that is rarely examined openly within modern Buddhist discourse.

The Four Activities as Magical Technologies

Tantric manuals from India and Tibet make explicit that the Four Activities are not metaphors. They are actionable ritual categories. Tantras such as the Guhyasamāja Tantra and the Hevajra Tantra, along with later ritual compendiums such as the Sādhanamālā and abhicāravidyā genre texts, provide detailed instructions for rites aimed at controlling weather, influencing rulers, compelling lovers, paralyzing rivals, or causing illness and death.[1]

These materials make clear that tantric ritual was never confined to inner transformation alone. The Four Activities structured a full spectrum of practical interventions into social, political, and psychological life.

The Sādhanamālā

The Sādhanamālā is a large Sanskrit compendium of tantric ritual manuals compiled in India roughly between the 8th and 12th centuries CE.

It is Buddhist, specifically Vajrayana or Mantrayāna, and not Śaiva, even though it shares techniques and ritual logic with non-Buddhist tantric traditions. The text consists of several hundred sādhana instructions for meditation and ritual practice focused on Buddhas, bodhisattvas, and tantric deities such as Tārā, Avalokiteśvara, Mañjuśrī, Vajrayoginī, and Hevajra.

Many of these sādhanas are explicitly or implicitly classified according to the Four Activities. They include ritual prescriptions for pacifying illness, enriching wealth or lifespan, magnetizing kings, patrons, or disciples, and subjugating enemies. The intended effects are practical and worldly as well as soteriological.

The Sādhanamālā was translated into Tibetan in parts and circulated widely in Tibet. Tibetan ritual literature draws heavily on this material, even when the Indian source material is not foregrounded explicitly.

Standard scholarly references include: Benoytosh Bhattacharyya, Sādhanamālā, Baroda, 1925–1928, and

David Snellgrove, Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, Shambhala, 1987.

Abhicāravidyā Texts

Abhicāravidyā is not a single book but a category of ritual literature.

The Sanskrit term abhicāra refers to rites of coercion, harm, or destructive magic. Vidyā means a spell or magical formula. Abhicāravidyā texts are therefore manuals of destructive or coercive rites.

In Buddhist tantra, such texts describe subjugation practices including immobilization, madness, illness, death, expulsion of consciousness, and rites intended to cause death, sometimes described as ritual killing by proxy. These rites are usually justified as actions taken against enemies of the Dharma, oath breakers, or beings deemed karmically irredeemable.

These texts circulated in India among tantric specialists and were selectively translated into Tibetan, often under euphemistic titles or embedded within larger ritual cycles. In Tibet, their contents were reorganized under the heading of drag po, or wrathful activity.

Important examples of Buddhist abhicāra material appear in:

The Guhyasamāja Tantra and its explanatory tantras

The Hevajra Tantra

The Sarvatathāgatatattvasaṃgraha

Later ritual manuals attributed to figures such as Nāgārjuna and Padmasambhava

Because of their ethical volatility, abhicāra rites were rarely taught openly. Access was restricted, which is one reason modern practitioners often underestimate how central such practices were historically.

Key scholarly discussions include: Ronald Davidson, Indian Esoteric Buddhism, Columbia University Press, 2002, and Alexis Sanderson, “The Śaiva Age,” in Genesis and Development of Tantrism, Tokyo, 2009.

Relationship to Tibetan Buddhism

Tibetan Buddhism inherited these Indian materials largely intact. The Four Activities framework in Tibet is not an innovation but a systematization of Indian tantric categories.

What changed in Tibet was less the ritual content than the doctrinal rhetoric surrounding it. Destructive and coercive rites were reframed as compassionate acts performed by realized beings. This rhetorical move allowed the practices to survive while softening their public presentation.

When Tibetan teachers speak of the Four Activities today, they are standing on a ritual foundation built by Indian Buddhist tantra, including the Sādhanamālā and abhicāravidyā traditions, whether this inheritance is acknowledged or not.

In Tibetan contexts, this ritual material was further systematized. The Four Activities became a classificatory framework under which thousands of rites were organized. Fire pujas, effigy magic, thread-cross rituals, and sexual yogas all find their place within this scheme.[2]

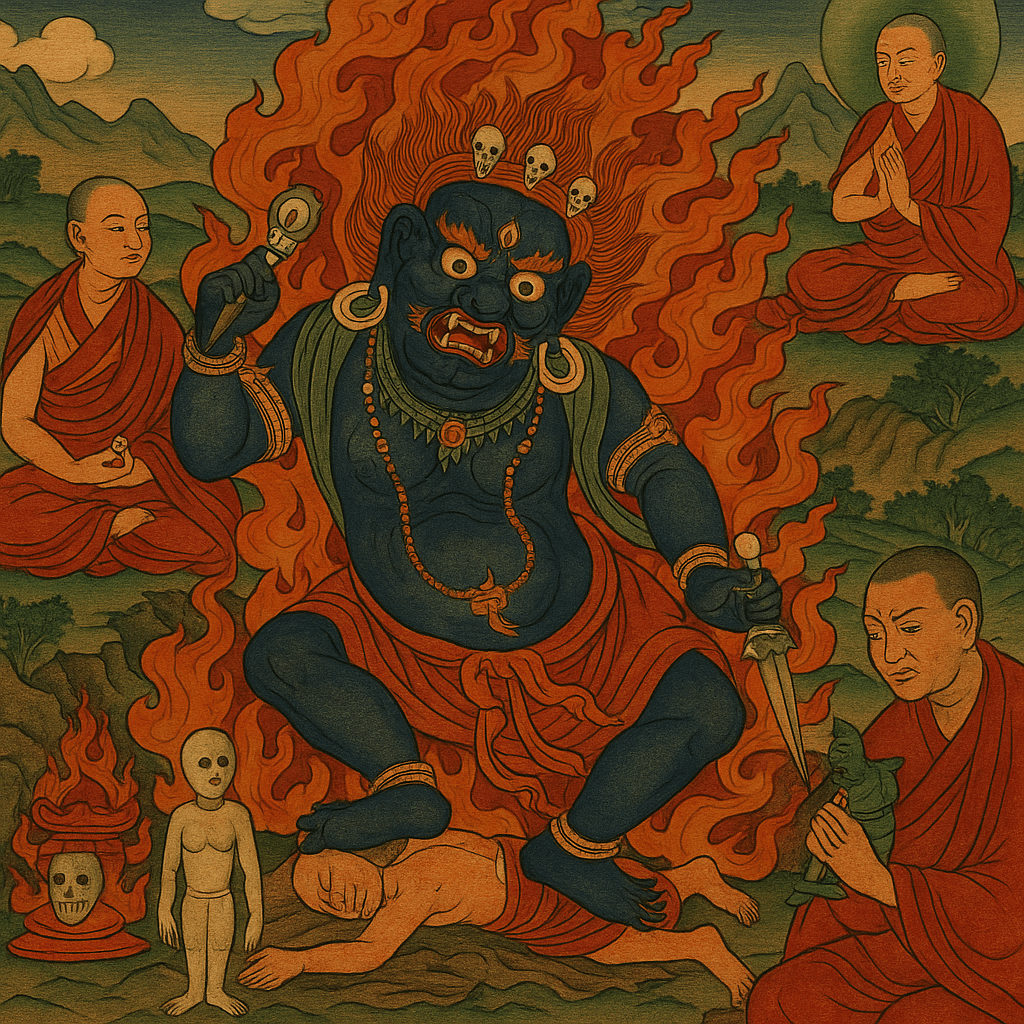

The ethical difficulty is obvious. While pacifying and enriching activities can be interpreted charitably, subjugation practices explicitly involve violence, coercion, and psychological domination. Tibetan ritual manuals state that subjugation rites can cause madness, death, or rebirth in hell realms for the target, often justified by vague claims that the victim is an enemy of the Dharma.[3]

Subjugation and Buddhist Ethical Dissonance

From the standpoint of Buddhist ethics, subjugation is the most troubling of the Four Activities. Buddhism is grounded in non-harming and the cultivation of compassion. Yet subjugation rituals rely on wrathful intent and instrumental harm. Traditional defenses argue that enlightened beings act beyond dualistic morality because they have transcended good and evil.

For modern Western practitioners, these explanations often remain abstract. Teachers rarely teach subjugation practices explicitly, and students are encouraged to interpret wrathful deities symbolically. This produces a form of cognitive dissonance. The practices exist, are preserved, and are sometimes performed within group pujas, but disciples can maintain psychological distance by not understanding the wrathful practices or details. Ignorance becomes a form of insulation.

Magnetizing Activity and the Binding of Disciples

Magnetizing activity is often portrayed as benign. It is described as the compassionate attraction of beings to the path. Yet tantric texts are explicit that magnetizing rites are used to influence minds, bind loyalty, and generate devotion.[4]

In ritual manuals, magnetizing practices are used to attract lovers, patrons, followers, and students. They involve visualizations of cords, hooks, nooses, and substances entering the bodies of targets to incline their thoughts and emotions. These are not metaphors for persuasion. They are magical technologies of attachment.

Within guru-disciple relationships, magnetizing activity takes on a particularly disturbing dimension. Once a student takes tantric initiation, they are bound by samaya vows. These vows often include lifelong loyalty to the guru and lineage until enlightenment is achieved.[5]

The power imbalance is severe. The teacher is positioned as the embodiment of awakening. The student is warned that doubt, criticism, or separation leads to spiritual ruin.

What If Enlightenment Is Not Reached?

Traditional literature assumes enlightenment will be reached. But what if it is not. What if the practitioner becomes disillusioned, traumatized, or psychologically destabilized.

In such cases, the Four Activities do not disappear. The same ritual logic that binds can also be used to punish. Tibetan sources describe the use of subjugation rites against oath breakers, samaya violators, and enemies of the lineage.[6]

Modern scholars and psychologists studying tantric communities have documented patterns of dependency, identity collapse, and long-term trauma following abusive guru relationships.[7] Magnetizing activity, in this light, resembles a spider’s web. Attraction is not neutral. It is structured, adhesive, and difficult to escape.

Conclusion

The Four Activities are not merely poetic descriptions of enlightened compassion. They are historical and functional systems of magical action. To ignore this is to misunderstand tantra at its core.

Subjugation challenges Buddhist ethics directly. Magnetizing challenges them more subtly. It operates through devotion, love, and surrender, making it easier to accept and harder to question. For Western practitioners kept deliberately ignorant of these dynamics, the result is not safety but vulnerability and the possibility of ruin.

An honest engagement with tantra requires confronting these practices without romanticism, without denial, and without pretending that malevolent harm disappears simply because it is cloaked in sacred language.

Footnotes and Sources

- Alexis Sanderson, “The Śaiva Age,” in Genesis and Development of Tantrism, Tokyo, 2009.

- Samten Karmay, The Arrow and the Spindle, Mandala Book Point, 1998.

- Ronald Davidson, Indian Esoteric Buddhism, Columbia University Press, 2002.

- David Gordon White, Kiss of the Yogini, University of Chicago Press, 2003.

- Jamgön Kongtrul, The Torch of Certainty, Shambhala, 1977.

- Stephen Beyer, The Cult of Tārā, University of California Press, 1978.

- Mariana Caplan, Halfway Up the Mountain, Hohm Press, 2011.