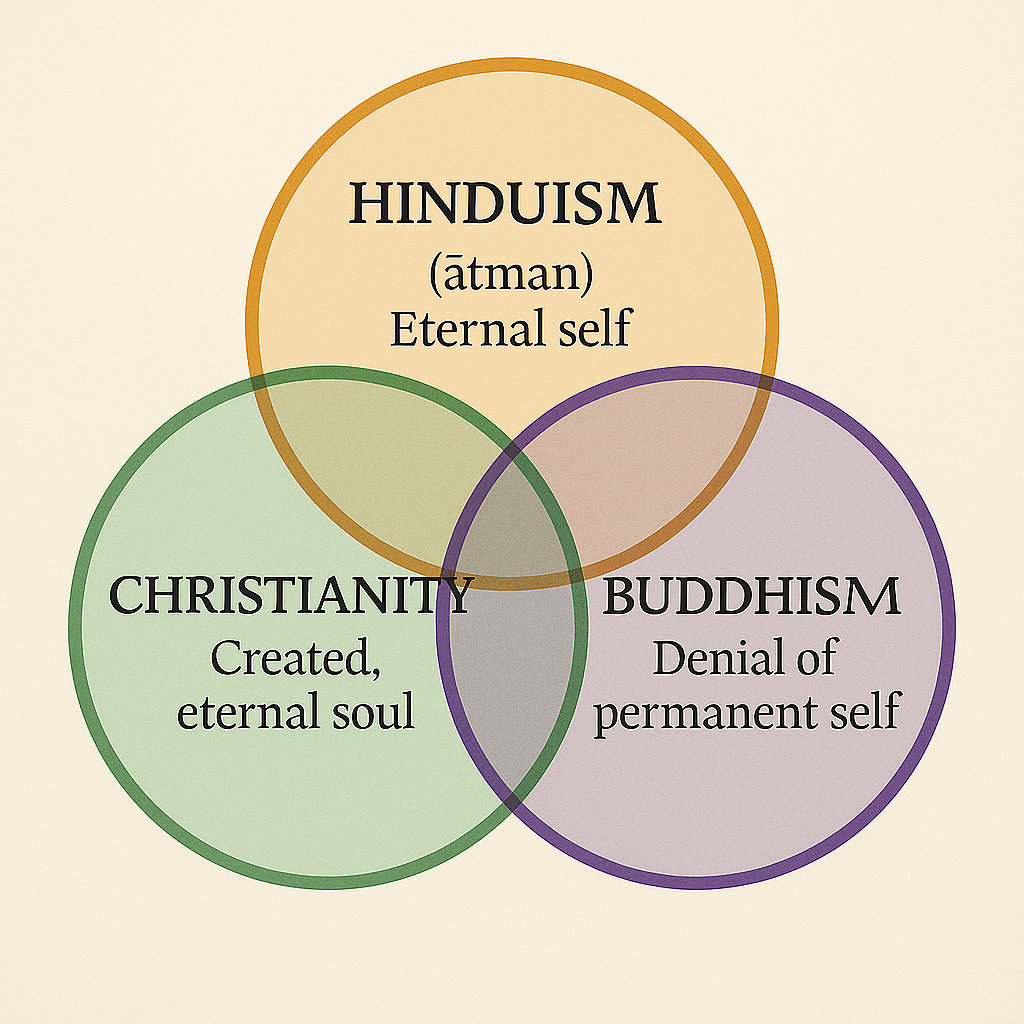

The question of what the soul is, whether it exists, and what happens to it after death lies at the center of the world’s major religious traditions. Christianity, especially in its Catholic tradition, affirms the soul as eternal and God-given. Hinduism has multiple schools, often affirming an eternal self or ātman. Buddhism, including Tibetan Buddhism, rejects the idea of a permanent self or soul and instead speaks of mind and consciousness as a conditioned stream of awareness without enduring essence.

The Christian and Catholic Understanding of the Soul

Christianity teaches that every human being has a unique, immortal soul created by God. According to Catholic doctrine, the soul is the spiritual principle of the human person. It is eternal in destiny, surviving bodily death, and directed either toward communion with God or separation from Him.

Scriptural sources include Genesis 2:7, where God breathes life into Adam and he becomes a living soul [1]; Matthew 10:28, where Jesus warns of the danger of losing the soul [2]; and the Catechism of the Catholic Church, which affirms that the soul is created by God and immortal [3]. In this view, the soul is not an impersonal principle but a personal identity, judged and redeemed by God.

Hindu Views on the Self (Ātman)

Hinduism is diverse, but most of its classical schools affirm the existence of ātman, the true self. The Chandogya Upanishad teaches “tat tvam asi” (you are that), affirming the identity of the self with Brahman [4]. The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad declares, “This self (ātman) is indeed Brahman” [5]. The Bhagavad Gita teaches that the self is eternal and indestructible [6].

Distinguishing Hindu and Christian Concepts

Both Hindu and Christian traditions speak of something enduring at the core of human existence, but they do so in different ways.

Christianity teaches that the soul is created by God, personal, and accountable before Him. It does not preexist from eternity but comes into being by His will and remains dependent on Him for existence, judgment, and salvation.

In Hindu thought, Advaita Vedānta emphasizes the identity of the self (ātman) with Brahman, dissolving individuality into the absolute. Dvaita and many Bhakti traditions instead teach that the self remains distinct yet eternal, existing in relationship with the divine. In all of these cases, the ātman is uncreated and co-eternal with ultimate reality, not brought into being by God.

Thus, while both traditions sometimes use personal and sometimes abstract language, the Christian soul and the Hindu ātman play very different roles. The soul in Christian theology is a created person before God; the ātman in Hindu philosophy is an eternal essence, whether one with Brahman or distinct in devotion.

The Creator God in Christianity and Hinduism

Christianity affirms one personal Creator God who brings the universe into being from nothing and sustains it in existence.

Hinduism presents a wide range of views. In Bhakti traditions, deities such as Vishnu, Shiva, or Devi are worshiped as supreme creators. Vedānta schools affirm Brahman as the ultimate source, though in Advaita this is not a personal act of creation but the manifestation of māyā. Other schools such as Sāṃkhya and Mīmāṃsā reject a creator altogether, viewing the universe as self-arising.

Thus, while Christianity grounds the soul in a personal God who creates and judges, Hindu thought ranges from devotion to a personal creator to cosmologies where no creator is necessary.

Buddhist Rejection of the Soul

Buddhism arose in part as a rejection of the Hindu doctrine of ātman. In the Anattalakkhana Sutta, the Buddha declared that none of the five aggregates of existence constitute a self [7]. The doctrine of anātman (no-soul) became central.

Mind and Consciousness

In Tibetan Buddhism, mind and consciousness are viewed as a stream of awareness, conditioned by karma. The Abhidharma-kośa describes consciousness as momentary and dependent [8]. Unlike Christianity and Hinduism, which affirm an eternal principle (soul or self), Buddhism denies it, calling belief in permanence a delusion.

Yet questions arise. If there is no soul, then what suffers in the hell realms described in Tibetan texts? The Bardo Thödol warns of the horrors of the Vajra Hell, a realm said to be utterly without escape [9]. The Hevajra Tantra declares that those who violate tantric commitments “will not be liberated for as many eons as there are atoms in the universe” [10]. The Cakrasaṃvara Tantra and later commentaries also teach that breaking tantric vows leads to vajra hells without release [11].

This presents a paradox: if there is no enduring self, who is suffering eternally?

Tibetan Buddhist Schools Under Examination

Madhyamaka – Nāgārjuna’s Mūlamadhyamakakārikā argues that all phenomena, including the self, are empty of inherent existence [13]. But if the self is an illusion, how does karma persist? If Vajra Hell is eternal, how can something that does not exist suffer forever?

Yogācāra (Mind-Only) – The Yogācārabhūmi Śāstra introduces ālayavijñāna, the “storehouse consciousness,” which preserves karmic seeds [14]. Though intended to avoid affirming a self, it functions much like one: carrying memory, identity, and karma. Hinduism here provides a comparison: the Bhagavad Gita teaches that the self carries karma through many births [6]. Yogācāra denies the term “soul,” yet reintroduces something strikingly similar. Christianity differs again: not a karmic storehouse, but a personal soul created by God.

Dzogchen (Great Perfection) – Dzogchen teachings, such as the Kunjed Gyalpo (All-Creating King), speak of rigpa, primordial pure awareness that is timeless and luminous [15]. Though Dzogchen denies that rigpa is a soul, the resemblance is striking. If rigpa is eternal, pure, and the ground of all experience, how is this different from what Christians call the soul or Hindus call ātman? The denial seems rhetorical rather than substantive.

Vajrayāna and Deity Possession – Tantric scriptures describe deity yoga, in which practitioners invite deities to merge with them [16]. If there is no self or soul, what exactly is being merged with or possessed?

Conclusion

Across Christianity, Hinduism, and Buddhism, the question of what endures, what we might call the soul, self, or consciousness, reveals fundamentally different views of human identity. Christianity anchors personhood in a created, immortal soul made by God and accountable to Him. Hinduism envisions an eternal ātman, uncreated and either one with or distinct from the divine. Buddhism, in contrast, denies any enduring essence, seeing the sense of self as a conditioned process. Yet in its Tibetan forms, teachings on karmic continuity, primordial awareness, and tantric transformation often edge back toward affirming something that functions like a self.

From long immersion in both Catholic and Tibetan Buddhist traditions, I have come to believe that the Christian vision alone sustains coherence between moral responsibility, continuity of consciousness, and the promise of redemption. It affirms not only that we exist, but that we are known and loved by the One who created us. Against the shifting alternatives of an impersonal absolute or an empty stream of awareness, in my opinion, the Christian understanding of the soul remains the clearest expression of what it means to be human before God.

References

[1] Genesis 2:7, The Holy Bible (ESV).

[2] Matthew 10:28, The Holy Bible (ESV).

[3] Catechism of the Catholic Church, Part I, Section Two, Chapter One, Article 1, §366.

[4] Chandogya Upanishad 6.8.7, in Radhakrishnan, S. (trans.), The Principal Upanishads.

[5] Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 4.4.5, in Olivelle, P. (trans.), The Early Upanishads.

[6] Bhagavad Gita 2.20, in Zaehner, R. (trans.), The Bhagavad-Gita.

[7] Anattalakkhana Sutta (Samyutta Nikaya 22.59), in Bhikkhu Bodhi (trans.), The Connected Discourses of the Buddha.

[8] Vasubandhu, Abhidharma-kośa.

[9] Bardo Thödol (Tibetan Book of the Dead), in Evans-Wentz, W.Y. (ed.).

[10] Hevajra Tantra, Snellgrove, D.L. (trans.), The Hevajra Tantra: A Critical Study.

[11] Cakrasaṃvara Tantra, in Tsuda, S. (trans.), The Samvarodaya Tantra.

[12] Hevajra Tantra, ibid.

[13] Nāgārjuna, Mūlamadhyamakakārikā, Kalupahana, D.J. (trans.).

[14] Yogācārabhūmi Śāstra, Xuanzang (trans.).

[15] Kunjed Gyalpo (All-Creating King), in Namkhai Norbu (trans.), The Supreme Source.

[16] Cakrasaṃvara Tantra and Hevajra Tantra, ibid.