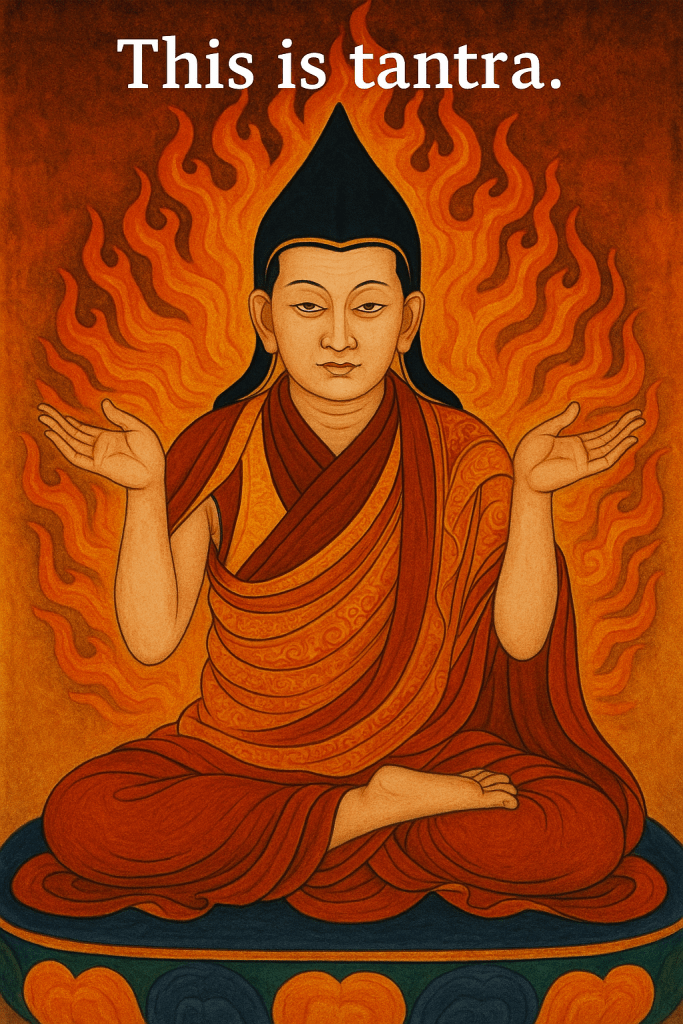

Among the many images that circulate quietly within Tibetan tantric lineages, there are several that are never explained to most practitioners and never shown outside advanced ritual contexts. One such image, often embedded within long Mahākāla rites and other high-level tantric liturgies, depicts a bound, pierced, weapon-studded human figure marked with mantras, seals, and symbolic restraints. To the uninitiated, it resembles a wrathful medical diagram or an esoteric curse talisman. To insiders, it represents something much more disturbing.

These images are not symbolic reminders of compassion, nor are they abstract metaphors for ego-death. They are ritual instruments. Specifically, they are used in rites intended to punish, bind, obstruct, or destroy the lives of those who are deemed to have broken samaya—the sacred vows binding a tantric practitioner to their guru, lineage, and yidam deity.

This fact is rarely discussed openly. When it is mentioned at all, it is framed euphemistically as “removing obstacles,” “protecting the Dharma,” or “subjugating harmful forces.” What is almost never acknowledged is that, within some tantric systems, the “harmful force” being targeted is a former disciple.

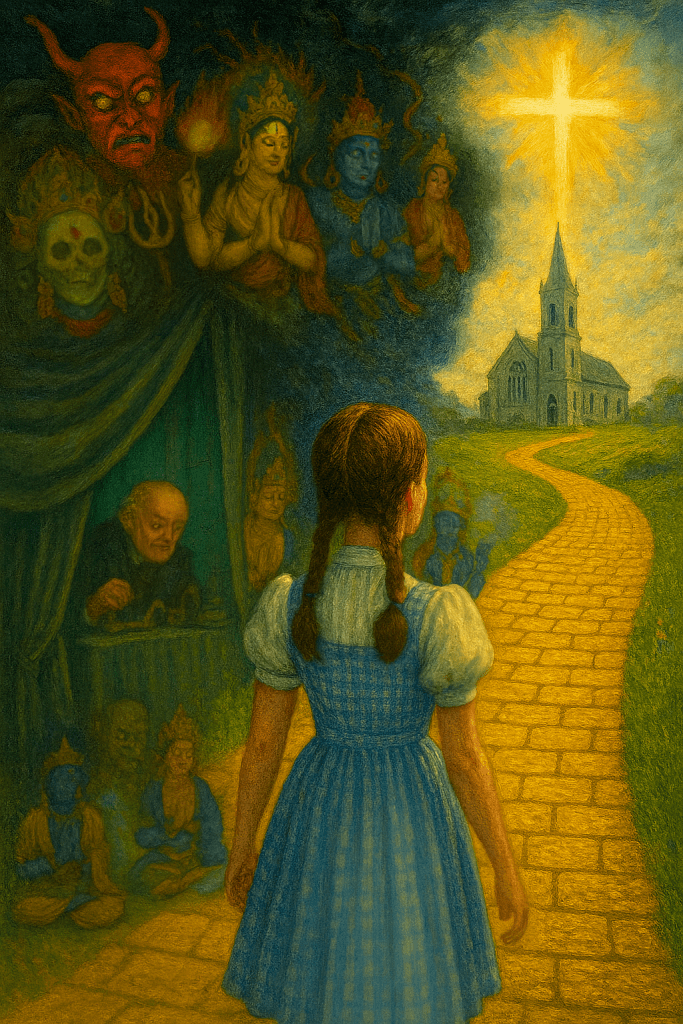

Why Beginners Are Never Told

Students entering Tibetan Buddhism are typically introduced through ethics, meditation, philosophy, and aspirational ideals: loving-kindness, compassion, non-violence, and wisdom. Tantric Buddhism is presented as a fast but benevolent path, dangerous only insofar as it requires devotion and discipline.

What they are not told is that questioning, criticizing, or emotionally reacting to a guru can itself be framed as a samaya violation. Nor are they told that certain rituals explicitly teach that lineage holders have the right, and sometimes the obligation, to retaliate metaphysically against perceived betrayal.

Beginners are warned vaguely that breaking samaya leads to “terrible consequences,” often described as karmic rather than intentional. The implication is that the universe itself will respond. What is left unsaid is that these consequences may be deliberately invoked, ritualized, and sustained by human agents acting within a tantric framework.

The unspoken lesson is simple: dissent is dangerous.

The Yidam Is Watching

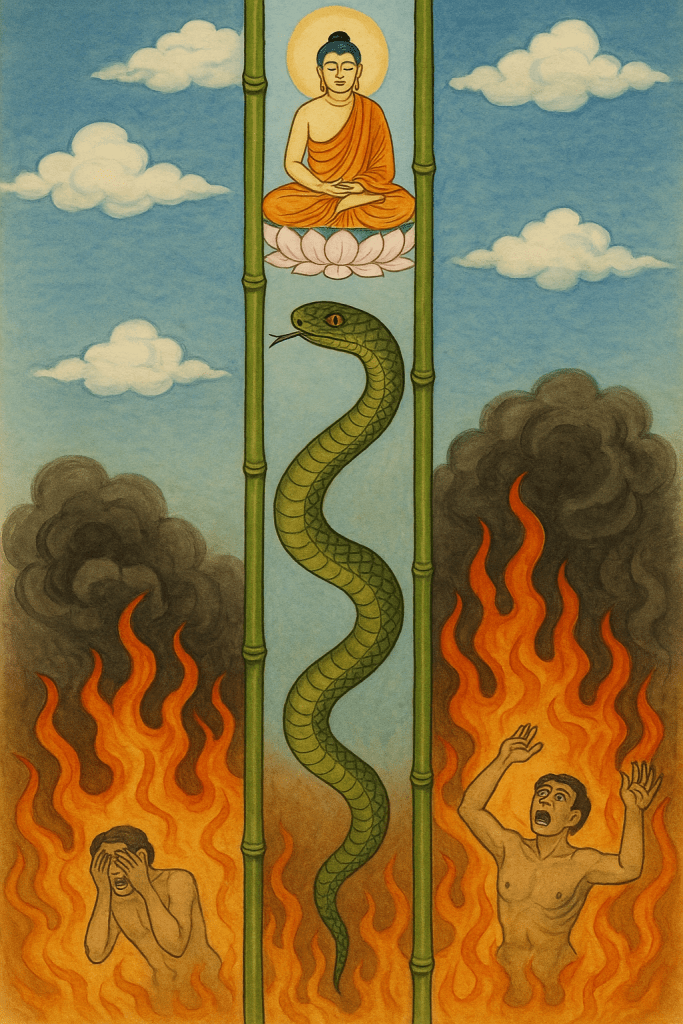

At the core of highest yoga tantra is the yidam deity, the meditational deity with whom the practitioner forms an exclusive, intimate bond. The yidam is not merely visualized as an external symbol but is gradually internalized, embodied, and ultimately identified with as one’s own enlightened nature.

This process is often described in modern terms as psychological transformation. In traditional terms, however, it is far closer to classical possession.

The practitioner receives initiation from a master understood to be fully realized–meaning fully inhabited by the yidam. Through empowerment, mantra recitation, repeated visualization, and ritual invitation, the practitioner repeatedly invites the deity to enter their body and mind. Over time, the boundary between practitioner and deity is intentionally dissolved.

This is how the yidam “monitors” the practitioner: not metaphorically, but through total psychic access. Thoughts, emotions, doubts, and impulses are no longer private. They are offerings or offenses.

Within this framework, enlightenment, siddhis, and protection are granted conditionally. The deity gives, and the deity can withhold. More disturbingly, the deity can retaliate.

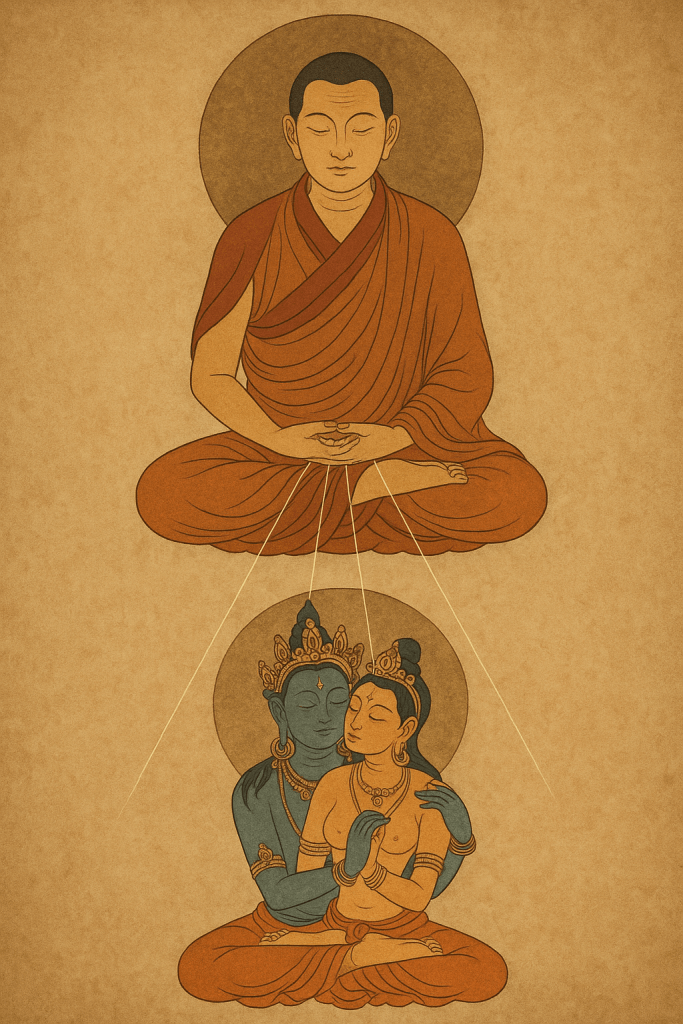

“Sons” of the Deity and Absolute Obedience

Advanced tantric systems often refer to lineage masters as the “sons” of the yidam. These are the men who have fully merged with the deity through practice. Disrespecting such a figure is not treated as a social conflict or ethical disagreement; it is framed as an attack on the deity itself.

This becomes especially dangerous in cases involving sexual relationships between guru and disciple. While not every such relationship is abusive, many are. In some cases, a guru expects sexual access as a demonstration of devotion and service. When the disciple becomes distressed, confused, or resistant, or when she later speaks out, the guru’s response is not accountability but punishment.

From within the tantric logic, the guru is not merely a man abusing power. He is a god-being whose will cannot be questioned. The disciple’s suffering is reframed as karmic purification or divine retribution.

Ritual Retaliation Is Real

There is a tendency among modern defenders of Tibetan Buddhism to dismiss accounts of retaliation as superstition or paranoia. Yet whistleblowers, both Western and Asian, have repeatedly documented actions taken against former disciples over months or years. In the most extreme cases, these are not momentary curses but sustained practices intended to ruin health, relationships, livelihood, and sanity.

I personally have known three gurus who engaged in such retaliatory behavior. These were not fringe figures. They were respected, accomplished masters with devoted followings. The rituals were not symbolic. They were methodical, intentional, and experienced by the practitioners themselves to be effective.

This is witchcraft in the plain sense of the word. It is no different in structure or intent from Haitian vodou curses or European malefic magic. The only difference is the religious branding.

The Ethical Contradiction at the Heart of Tantra

This raises an unavoidable question: how can a system that claims descent from the historical Buddha whose teachings emphasize non-harming, restraint, and compassion contain practices that deliberately destroy human lives?

The answer lies in tantric exceptionalism. Within these systems, ordinary Buddhist ethics are considered provisional. Once one enters the tantric domain, morality becomes subordinate to obedience, secrecy, and power. A guru possessed by a wrathful deity is no longer bound by conventional ethics because the deity is not.

Publicly, tantric masters speak constantly of compassion and loving-kindness. They smile, bless, and perform virtue with great skill. Privately, nothing is free. Every empowerment creates obligations. Every vow tightens the noose. And the deeper one goes, the more rigid and unforgiving the system becomes.

The Real Danger

Not all Tibetan Buddhist teachers engage in these practices. Many do not. But the fact that some of the most accomplished masters have done so for centuries means the danger is structural, not incidental.

The real threat of tantric Buddhism is that it weaponizes devotion, sanctifies possession, and normalizes ritual violence while hiding behind the language of Buddhist compassion and enlightenment.

Until this is openly acknowledged, aspirants will continue to walk blindly into systems that can, and sometimes do, destroy them, all in the name of awakening.