In Tibetan tantric Buddhism, the relationship between guru and disciple is said to be sacred, a channel for transmission of enlightenment itself. Yet within that same structure lies a potential for absolute domination. When a guru feels threatened, betrayed, or exposed, the same system that demands devotion can become an instrument of terror.

The tantric logic of punishment

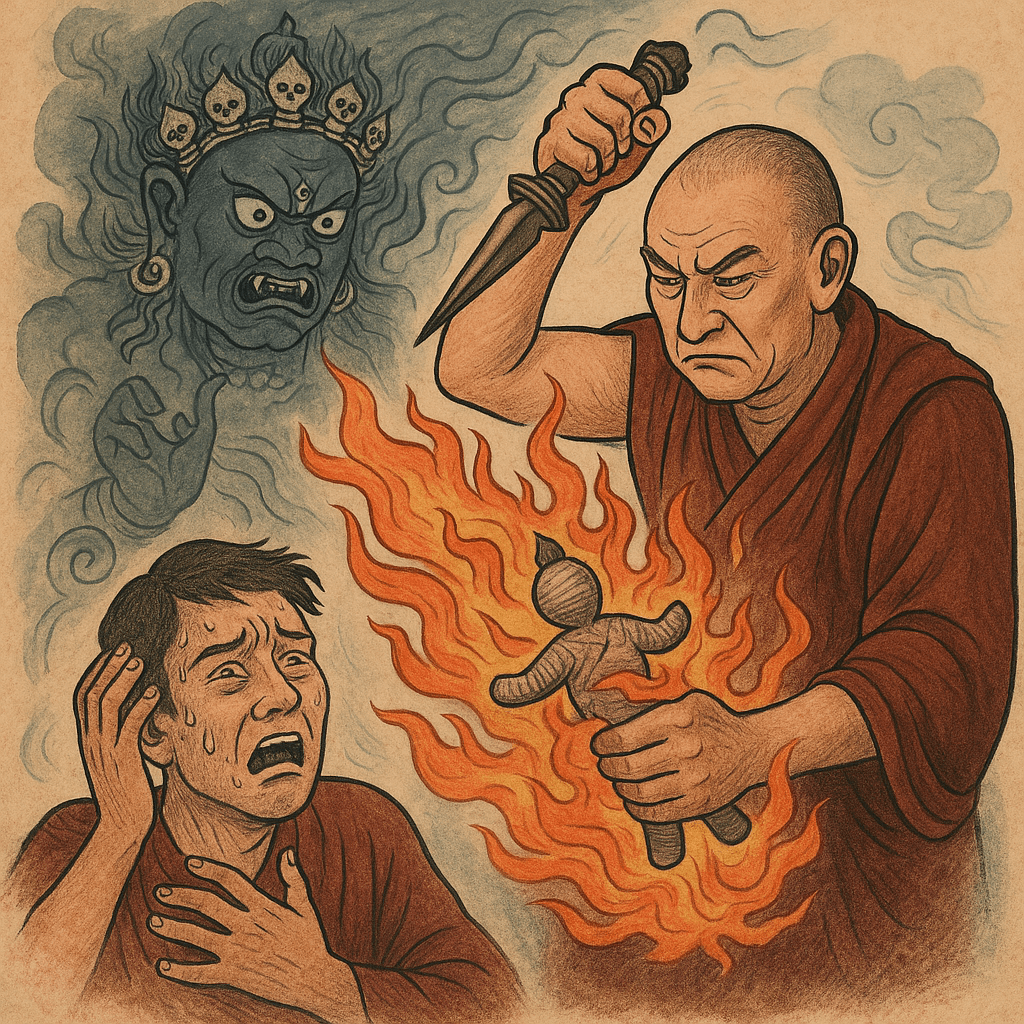

In tantric doctrine, every vow (samaya) between guru and disciple is a metaphysical bond. Breaking it is said to unleash cosmic consequences. Ancient texts speak of wrathful deities and oath-bound protectors who punish those who “slander the guru” or “harm the Dharma.” The idea is not metaphorical. Illness, accidents, or misfortune are interpreted as visible proof that unseen forces are enforcing spiritual law.¹

A guru who believes this, and who claims mastery of the dark ritual practices that command those forces, often teaches others to believe it. That teacher wields enormous psychological power. To label someone a “samaya-breaker” is to mark them as deserving of sickness or death. This is not an internal accusation only; it shapes the views of the community where the guru holds god-like power. It gives the guru a pretext to use ritual methods to harm students whenever he deems it necessary.

Entities that cause disease

Traditional Tibetan cosmology offers a detailed taxonomy of spirits believed to cause physical and mental harm: bdud (demons), gdon (malevolent spirits), btsan (fiery mountain gods), klu (serpent beings of water), and srin po (ogres).² Each category is said to afflict a different organ, emotion, or realm of life. Texts such as René de Nebesky-Wojkowitz’s Oracles and Demons of Tibet describe elaborate systems of offerings and threats designed to control these beings.

Within this worldview, ritual specialists do not invent malevolent forces but redirect them. A demon bound by oath can be petitioned to punish a perceived oath-breaker. Protector deities can be asked to “remove obstacles” by striking enemies with disease or madness. These ideas are deeply embedded in tantric liturgy and methodology, even if modern dharma centers prefer to describe them symbolically.

The internal logic of coercion

When this metaphysical framework meets the authoritarian structure of a retreat or monastic hierarchy, the result can be catastrophic.³ Gurus can claim divine justification for acts that would otherwise be seen as abusive. If a disciple questions orders, refuses sexual advances, or tries to leave, the teacher can declare them in spiritual violation. From that point on, any misfortune that follows can be attributed to supernatural punishment rather than the guru’s actions.

Real world allegations

The potential for that logic to cross into criminal abuse is not theoretical. Adele Tomlin has published a series of testimonies from women who participated in long-term tantric retreats under the auspices of major Tibetan Buddhist organizations in the United Kingdom and Nepal. According to Tomlin’s report, complaints were submitted to trustees of the dharma centers, as well as to resident teachers. Police reports were also made, with at least one woman reportedly informed that criminal acts had occurred.

The list of complaints is substantial: “…sexual harassment, sexual assault/coercion, ‘false imprisonment’ i.e. refusing to allow people to leave the retreat for urgent matters, such as medical diagnosis and treatment or due to psychological breakdowns, emotional bullying, insistence on signing non-disclosure legal agreements, refusal to provide proper aid to those in physical pain or serious sickness. It was reported that women who had requested to leave the retreat for the above reasons were responded to with threats that they would go to hell…and telling them they would have short lives, terrible sicknesses and their family members would die and get sick too.” There are also accounts of tantric rituals being misused “to ‘force’ consorts to engage in ‘subtle body energy’ unions without appropriate consent/devotion or even pre-requisite qualifications of the guru or consort for such a relation,” and reports that participants’ passports were confiscated before entering retreats in Nepal.”³ See Tomlin’s article here.

The psychology of fear

Once a disciple internalizes the idea that disobedience invites divine punishment, ordinary safeguards such as the law, conscience, and community protection lose their power. The guru becomes both the source of danger and the only possible protection from it. Fear of sickness, insanity, or karmic ruin may keep followers silent even when they experience or witness abuse. This is coercive control disguised as spirituality.

Why tantra is uniquely risky

Every hierarchical religion can produce abuse, but tantric systems amplify the risk because they contain dark magical rituals that can be used to secretly harm students who do not show proper obedience. In the Tibetan tantric system, the guru is not just a teacher but the embodiment of enlightenment itself. Vows are said to bind across lifetimes. Breaking them is imagined to destroy spiritual progress and unleash demonic retribution. That belief gives abusive teachers a supernatural mandate to harm and a theological excuse when they do.⁴

Many practitioners are drawn to long-term retreats by tantra’s promise of transformation. But are the risks worth it? Without structural accountability, the same tools can become weapons. When secrecy, charisma, and ritual authority converge, even devoted, sincere, and intelligent students can be trapped in a reality of pain and punishment.

For those who have lived inside such systems, the scars run deeper than physical or sexual trauma. The damage is also ontological: the haunting sense that unseen forces will stalk them forever and that they are cursed beyond escape. Healing begins by reclaiming moral and spiritual agency, by recognizing that no guru, spirit, or protector holds dominion over one’s body, mind, or fate. Yet once that agency has been surrendered to powerful gurus and their invisible minions, recovering it can be very difficult.

Notes

- Stanley Mumford, Himalayan Dialogue: Tibetan Lamas and Gurung Shamans in Nepal (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989).

- René de Nebesky-Wojkowitz, Oracles and Demons of Tibet (The Hague: Mouton, 1956).

- Adele Tomlin sole author of Dakini Translations website: NOT SO “HOLY ISLE”? TRAGIC TALES OF REPORTED (AND ENABLED) BULLYING AND SEXUAL MISCONDUCT TOWARDS WOMEN AT SAMYE LING UK BUDDHIST CENTRES THAT ENDED IN PHYSICAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL HARM, ATTEMPTED SUICIDES AND MURDER. Article excerpted with attribution.

- Geoffrey Samuel, Civilized Shamans: Buddhism in Tibetan Societies (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993).