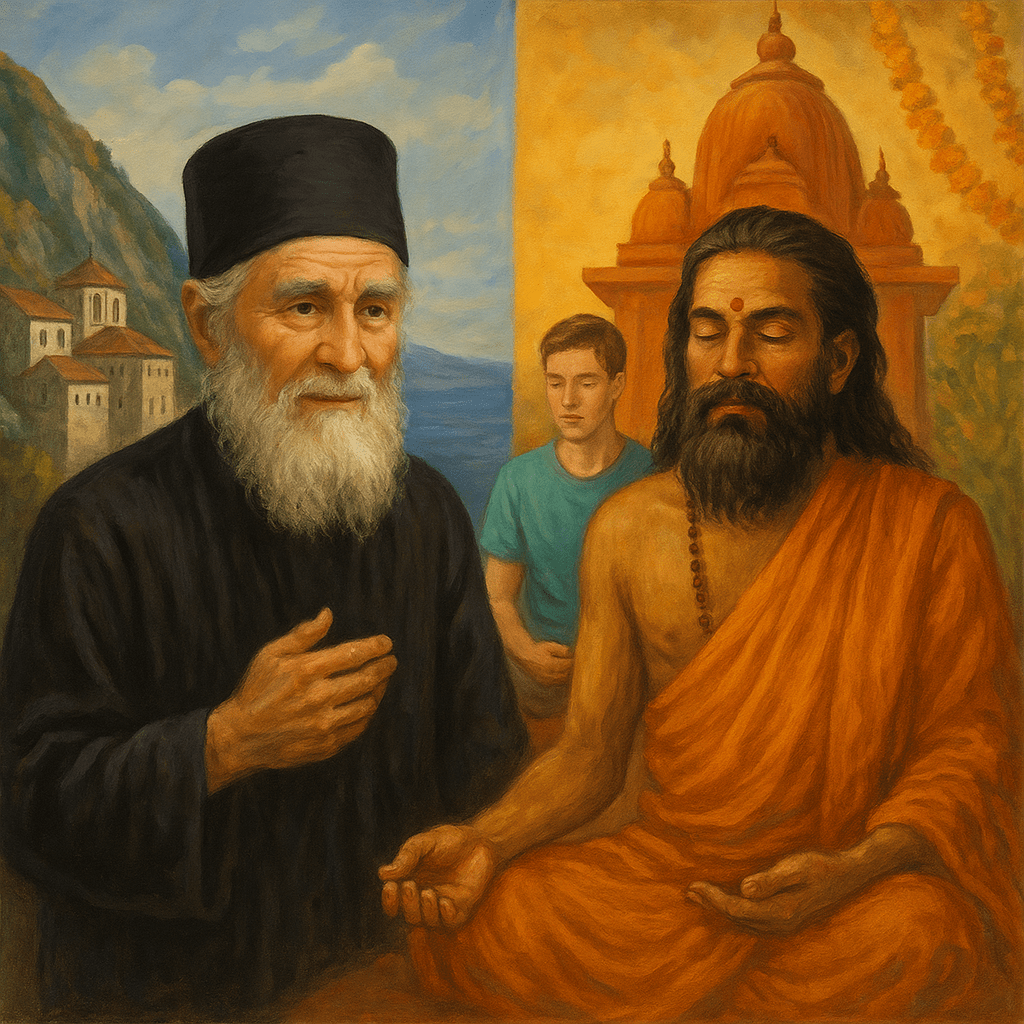

In 2008, the Holy Monastery of Saint Arsenios on Mount Athos published The Gurus, the Young Man, and Elder Paisios.¹ It tells the true story of a young Greek man whose hunger for spiritual depth led him from the monasteries of Athos to the ashrams of India, where he fell under the sway of a Hindu guru. This book resonated with me because it mirrors the restlessness of many modern seekers. It traces the arc from yearning for authentic experience, through dangerous detours into counterfeit light, and finally to deliverance through Christ. That theme, the need for discernment in a world of spiritual seductions, is central to my own story and to the explorations I share.

The First Encounter with Elder Paisios

The young man first encountered Elder Paisios on Mount Athos, the spiritual heart of Greek Orthodoxy. Athos is not simply a monastic peninsula but a living continuation of the desert fathers, a land saturated with centuries of prayer. Elder Paisios was already known as a man with the profound gifts of clairvoyance, discernment, and love. At the heart of Orthodoxy, he explained, lies the invocation of the name of Christ: “Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me.”² This is not a spiritual technique but a cry from the heart. As Paisios emphasized, “With the name of Christ we experience divine Grace, divine illumination, and union with God.”³

Life on Mount Athos

Mount Athos rises from the Aegean like a fortress of prayer. Approaching by boat, pilgrims see monasteries clinging to cliffs, their domes catching the morning sun. Bells toll at dawn, summoning monks from their cells to the katholikón, the central church. Inside, the air is heavy with incense; oil lamps flicker before icons blackened with centuries of smoke. The chanting is slow and unhurried, carrying the words of the Psalms like waves rolling in from the sea.

The rhythm of Athonite life is simple but relentless. To walk its paths is to feel the weight of prayer, as if the very stones are steeped in the remembrance of God. When the young man would meet Elder Paisios in his cell at Panagouda, he encountered not pomp or grandeur but humility. The elder sat on a rough stool, his clothes patched, his face lined with suffering yet radiant with joy. Paisios was accessible, direct, and utterly unpretentious. His authority did not come from outward spectacle but from the depth of grace shining through him.

Despite these encounters, the young man was restless. His desire for spiritual experience drew him beyond Orthodoxy and into Hinduism in India.

Life in the Ashram

India overwhelmed his senses. It was a riot of bright colors and potent scents. Bells clanged rhythmically at dawn, mingling with the chant of myriad voices repeating mantras. Bare feet shuffled across dusty courtyards as disciples hurried to gather at the feet of the guru, who sat elevated on a dais draped in silk and garlands of marigolds. The air around him was charged with expectancy.

Daily life in the ashram followed ritual precision. Before sunrise, disciples bathed in cold water, then filed into meditation halls where they repeated mantras by the thousands. Each syllable, they believed, vibrated with cosmic energy. The guru’s followers bowed low, sometimes lying full-length on the ground, convinced that to touch even the dust beneath his feet was a blessing.⁴ His faintest smile was received as a gift, his disapproval a knife wound.

The guru’s teachings promised transcendence. He insisted that the repetition of mantras would dissolve the ego and merge the self into the divine. He was not merely a teacher but the embodiment of truth itself. Service was considered worship: cooking his meals, arranging his seat, or waving fans before him was thought to create conditions conducive to liberation. At first, the young man was drawn in by the atmosphere of devotion and the apparent serenity of the disciples. The charged rituals, intense and mystical, seemed to hum with power.

Yet Elder Paisios had already warned him: “The invocation of the name of any other god apart from Christ is communion with demons. The person who invokes that name calls upon the demon corresponding to it and is possessed by it.”⁵ What seemed like nectar would prove to be poison.

Paisios explained that deceptive energies imitate grace: “They give a sweetness, a supposed peace, but afterwards they bring turmoil.”⁶ This was the young man’s experience. The chants that once filled him with calm soon unsettled him. His thoughts scattered, his dreams grew dark, and the guru’s gaze, once a source of comfort, became suffocating. The ashram that had promised freedom now felt like a dangerous place.

The Return to Mount Athos

When the young man finally returned to Athos and told Paisios everything, the elder spoke with clarity. “In Orthodoxy we have the invocation of the name of Christ. With it we experience illumination and union with God. All other invocations, all other names, apart from Christ, lead to deception.”⁷

Paisios prayed for him, invoking Christ. In that moment, the torment that had hounded the young man since the ashram lifted. He felt the peace of God return, and the tormenting voices were silenced. What the guru’s gaze and mantras had invoked, the simple name of Jesus restored.

Why It Resonates

This story mirrors my own path. Like the young man, I wandered away from Christ into Eastern occult traditions that promised transformation through techniques such as deity yoga, mantra repetition, and breath manipulation. The initial sweetness was very real followed by years of difficulties alternating with mystical heights, but all of that led to demonic possession by entities I once thought were buddhas.

In a world where esoteric practices are commonplace, Paisios’s warnings are urgent. Many today seek mystical experiences, but as Elder Paisios said, “Grace brings deep humility, contrition, tears, and love for Christ.”⁸ The counterfeit, by contrast, produces disturbance and bondage. The young man’s deliverance is not his story alone; it is a caution to the world that spiritual deceptions come at a terrible price.

Notes

- Dionysios Farasiotis, The Gurus, the Young Man, and Elder Paisios, trans. and adapted by Hieromonk Alexis (Trader), ed. Philip Navarro (Platina, CA: St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood, 2011).

- Farasiotis, The Gurus, the Young Man, and Elder Paisios, chap. 3.

- Farasiotis, The Gurus, the Young Man, and Elder Paisios, chap. 4.

- Farasiotis, The Gurus, the Young Man, and Elder Paisios, chap. 5.

- Farasiotis, The Gurus, the Young Man, and Elder Paisios, chap. 4.

- Farasiotis, The Gurus, the Young Man, and Elder Paisios, chap. 4.

- Farasiotis, The Gurus, the Young Man, and Elder Paisios, chap. 4.

- Farasiotis, The Gurus, the Young Man, and Elder Paisios, chap. 4.