As young Western seekers, we were told directly by the refuge lama, a highly accomplished yogi whose presence and meditative depth made his words seem authoritative, that we could be both Christian and Buddhist. He said there was no conflict, that a person could be both Christian and take refuge in Tibetan Buddhism. Only much later did I begin to see that the metaphysical claims of Christianity and Tibetan Buddhism do not sit comfortably together. When examined honestly they point in opposite directions. This article explores that truth and why the issue deserves more clarity than it usually receives.

The Christian indelible mark

Catholic teaching holds that baptism is not a symbolic rite. It confers a real spiritual character on the soul, a mark that is indelible and permanent.¹ The person baptized is said to belong to Christ in a definitive way. Even if one later rejects Christian belief, the character imprinted by baptism remains. This teaching forms a central claim about spiritual identity. Baptism is a covenant, a seal, and a bond that cannot be undone by human action. Some theologians and exorcists describe it as a spiritual allegiance that shapes the destiny of the person marked by it.²

Vows in Tibetan Buddhism

Tibetan Buddhism also understands vows as real phenomena rather than mental constructs. They are described as subtle forms that arise in the practitioner’s continuum and remain active as long as the vow is kept.

Refuge: The refuge vow is the foundation of the path. To take refuge is to entrust oneself entirely to the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha. This commitment is said to exist as a subtle form until broken.³

Bodhisattva vow: This vow stabilizes the intention to attain enlightenment for all beings. It is also considered to have ontological presence, shaping the practitioner’s moral and spiritual life.⁴

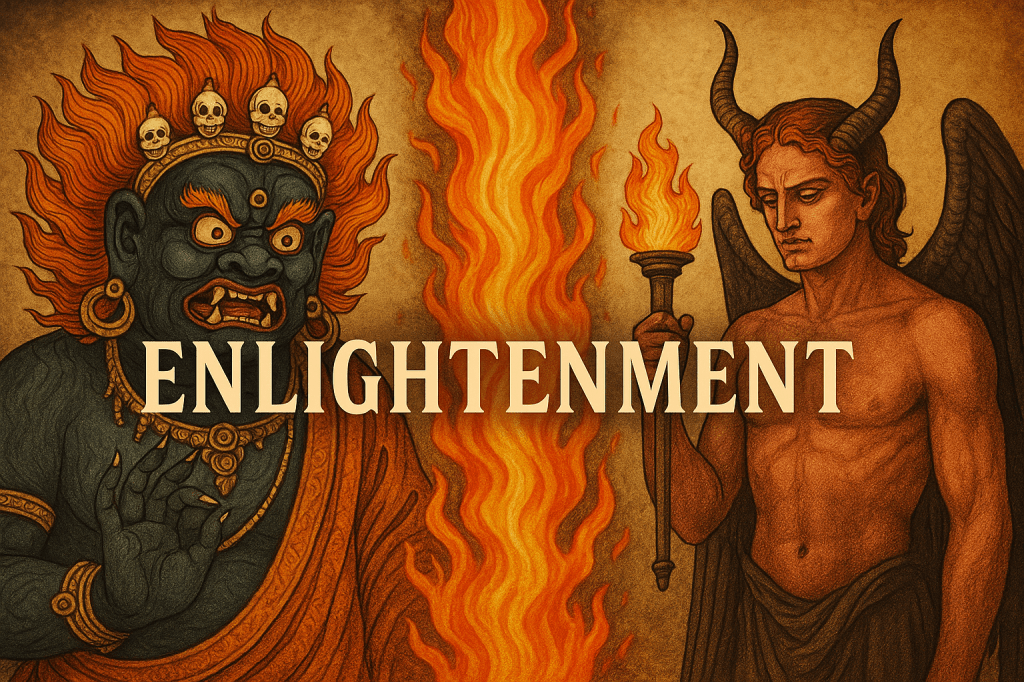

Tantric vows: Tantric samaya binds the practitioner to the guru, the deity, and the mandala. Tibetan commentaries treat samaya as a form that abides in the subtle body. Maintaining it is essential for any tantric practice to function. Breaking it has extremely dire consequences.⁵ Tantric vows require a view of reality that rejects any creator God and understands the deity as a manifestation of awakened mind.⁶

The awareness of the deities

What makes this tension even more striking is the role of the tantric deities. In traditional Tibetan understanding these deities are not abstract ideas. They are regarded as fully aware and responsive.⁶ When a practitioner takes refuge or samaya, the commitment is made not only in the presence of a human teacher but in the presence of the deity invoked.⁷

This means that even if a lama sincerely believes there is no conflict with Christianity, the deity knows exactly what commitments the practitioner brings into the mandala. The deity is aware of conflicting allegiances. If baptism marks a person as belonging to Christ, the tantric deity would encounter that mark as a pre-existing and incompatible bond.

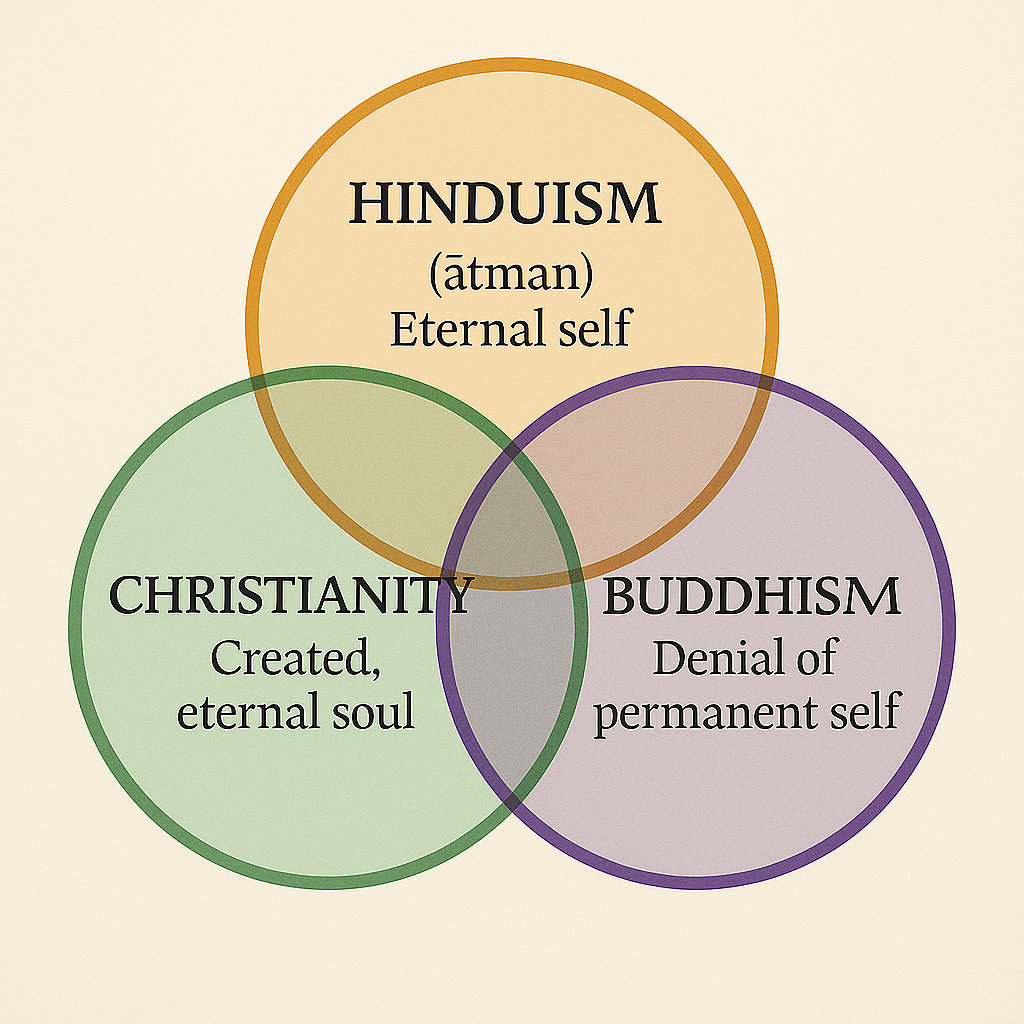

When my refuge lama told us that being Christian was no problem, I accepted his assurance. He was revered, a man of immense yogic accomplishment. Yet the actual teachings of the system he represented do not support his statement. Neither do the Christian teachings. Christianity requires allegiance to the Most High God and sees baptism as a permanent seal of belonging.⁸ Thus, the two religious systems do not fit together. They are not partial overlaps but mutually exclusive covenants.

The question of whether one can be both Christian and a Tibetan Buddhist practitioner is not merely philosophical. It concerns real commitments that each tradition claims have unseen but powerful form. To treat these vows and sacraments lightly is to misunderstand them. To treat them seriously is to recognize that both paths make exclusive claims on the identity and destiny of the practitioner. Honesty requires admitting that they cannot be combined without dissolving the integrity of one or the other.

Sources

¹ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2nd ed., §§1272–1274.

² Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, III, q. 63, aa. 1–6.

³ Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye, The Treasury of Knowledge, Book Six.

⁴ Je Tsongkhapa, The Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment, Vol. 1.

⁵ Khenpo Ngawang Pelzang, A Guide to the Words of My Perfect Teacher.

⁶ Patrul Rinpoche, The Words of My Perfect Teacher.

⁷ Dalai Lama and Alexander Berzin, The Gelug/Kagyu Tradition of Mahamudra, chapters on tantric initiation.

⁸ Benedict XVI, Address to the Roman Curia, 22 December 2006, section on baptismal identity.