Early Traces: The Nestorians and the Eighth Century

The history of Christianity in Tibet stretches back far earlier than most assume. The earliest Christian presence likely came from the Nestorian Church of the East, which had spread along Silk Road routes from Mesopotamia into China by the 7th century. Evidence from the Xi’an Stele of 781 CE shows that Nestorian missionaries were active under the Tang Dynasty, and given Tibet’s close relations with Tang China, it is plausible that Christian communities emerged within the Tibetan cultural sphere during the 8th century.1 However, these early Christian enclaves left no sustained legacy; Tibet’s conversion to Buddhism under Trisong Detsen soon dominated its spiritual landscape.

Jesuits in Guge: Antonio de Andrade and the Lost Kingdom

The next major encounter between Christianity and Tibet came through the Jesuit missions of the 17th century. In 1624, the Portuguese Jesuit Antonio de Andrade became the first known European to enter Tibet. He reached Tsaparang, the capital of the Guge Kingdom in western Tibet, where he was warmly received by King Tri Tashi Dakpa (also called Chadakpo). The king even laid the cornerstone for Tibet’s first church, completed in 1626.2

De Andrade’s arrival, however, sparked tensions. His success in converting local nobles alienated the powerful Buddhist clergy. A political conflict between the king and his brother, who was aligned with Buddhist monastics, led to the downfall of the Guge mission. Around 1630, the king was overthrown with assistance from the Ladakhi ruler Sengge Namgyal, who viewed Guge’s alliance with Catholic missionaries as a provocation.3 The Jesuits were expelled or killed, and Guge itself disappeared from the political map soon thereafter.

The Jesuits in Lhasa: Ippolito Desideri and the Capuchin Controversy

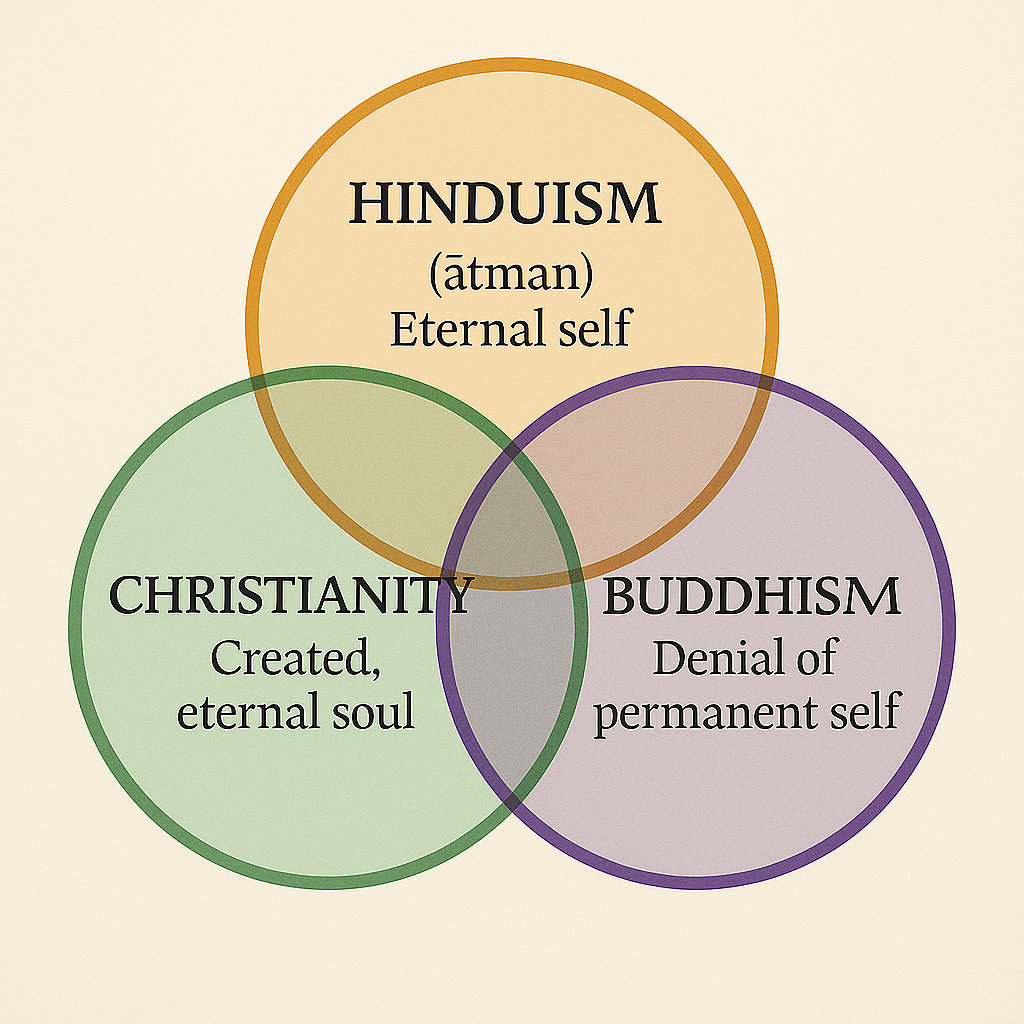

After Guge’s fall, the next great missionary endeavor came with Ippolito Desideri, an Italian Jesuit who reached Lhasa in 1716. Desideri immersed himself in Tibetan culture, mastered the language, and composed treatises comparing Christian and Buddhist metaphysics. His conciliatory approach, attempting dialogue rather than confrontation, won him both local sympathy and later admiration among scholars.4

Desideri’s work, however, was undone not by Tibetans but by Church politics in Rome. The Vatican’s Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith (Propaganda Fide) restructured Asian missions and in 1703 assigned Tibet to the Capuchins, a Franciscan order. The Jesuits were ordered to withdraw, leading to Desideri’s forced departure in 1721. The decision reflected not only internal rivalry but also a Vatican preference for an order more controllable and less inclined toward syncretic engagement.5

Suppression and Exile: The 18th and 19th Centuries

After the Jesuits’ departure, Capuchin missionaries continued their work until the 1740s. A crisis erupted in 1742, when a Tibetan convert refused to bow before the Dalai Lama, an act perceived as defiance against both religion and state. The government expelled the missionaries and banned Christianity in Central Tibet, a policy enforced by 1760.6

Despite this, individual attempts persisted. In the 19th century, the British missionary Annie Royle Taylor undertook a daring journey toward Lhasa in 1892, becoming the first Western woman to reach central Tibet, though she was ultimately turned back by Tibetan guards.7 Her journey epitomized the enduring fascination and futility of Christian outreach in a land long closed to foreigners.

Elsewhere, especially in eastern Tibet (Kham), anti-Christian sentiment often flared into violence. During the 1905 Batang Uprising, missionaries and Tibetan converts were targeted and killed. Among those martyred were André Soulié (1858–1905) and Jean-Théodore Monbeig-Andrieu (1875–1914), who are commemorated in Catholic hagiographies as victims of faith-driven hostility.8

The Vatican’s Strategic Shift: Why the Jesuits Were Replaced

The Vatican’s decision to replace the Jesuits with Capuchins was rooted in both theological and geopolitical concerns. The Chinese Rites Controversy (late 17th–early 18th centuries), in which Jesuits were accused of tolerating Confucian and local religious practices, had eroded papal trust. The Propaganda Fide viewed Jesuit accommodationism, especially Desideri’s open dialogue with Buddhist philosophy, as dangerous relativism. Capuchins, by contrast, were stricter and less likely to blur doctrinal lines. As historian Donald Lach notes, “the Capuchins represented the centralizing impulse of the Counter-Reformation, where obedience outweighed intellectual innovation.”9

Christianity and Modern Tibet: A Restricted Faith

Under Chinese administration since the 1950s, Tibet’s relationship with Christianity has remained tightly controlled. The People’s Republic of China recognizes only state-sanctioned religious institutions, and Catholic practice in the Tibet Autonomous Region exists only under the auspices of the Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association, which does not recognize Vatican authority. The Holy See’s cautious diplomacy, especially during Pope Francis’s efforts to reestablish relations with Beijing, has led to a de facto acceptance of limited Catholic presence, primarily among Han Chinese residents in Lhasa rather than ethnic Tibetans.10

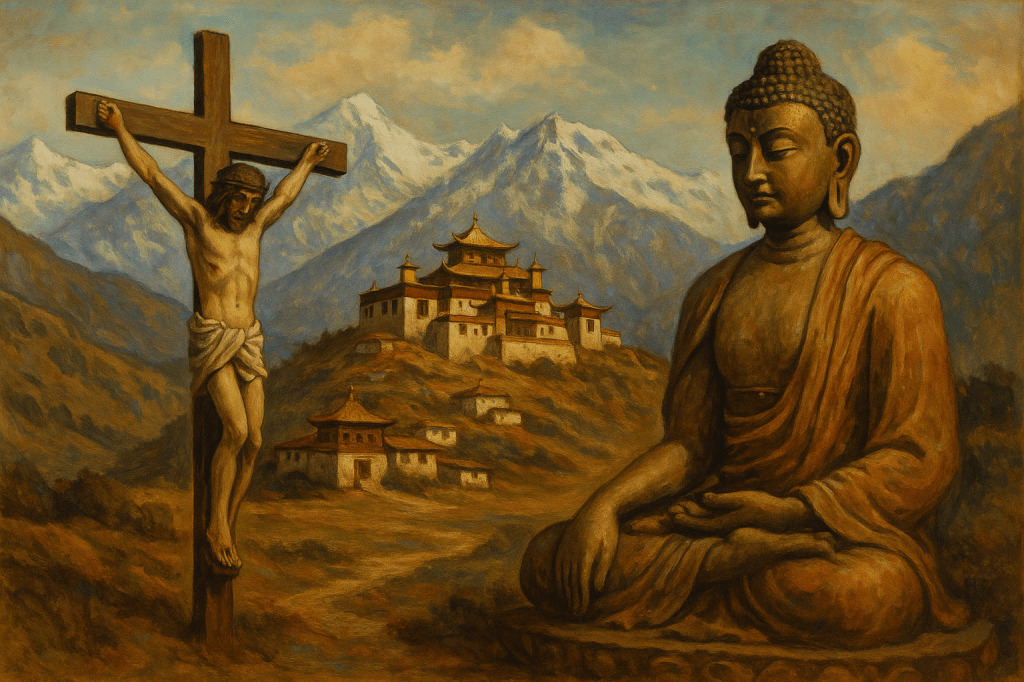

The Vatican continues to regard Tibet as part of its mission territory, but evangelization remains almost nonexistent. Tibetan Buddhism remains dominant, and Christian symbols such as crosses, churches, even icons are scarce across the plateau.

Legacy

From the Nestorian wanderers to Jesuit polymaths and Franciscan ascetics, Christianity’s story in Tibet is one of ambition, misunderstanding, and endurance. While never a major presence, its traces linger in forgotten ruins in Tsaparang, in Desideri’s Tibetan manuscripts preserved in Rome, and in the historical memory of dialogue between two of the world’s most mystical spiritual traditions.

Footnotes

- Samuel H. Moffett, A History of Christianity in Asia, Vol. I: Beginnings to 1500 (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1992), 291–295.

- Antonio de Andrade, Novo Descobrimento do Gram Cathayo ou dos Reinos de Tibet (Lisbon, 1626); Timo Schmitz, An Overview of Tibetan History (2025), 91–92.

- Le Calloc’h, J. (1991). “Antonio de Andrade and the Mission in Western Tibet.” Archivum Historicum Societatis Iesu, 60: 57–60.

- Ippolito Desideri, Notizie Istoriche del Tibet (Rome, 1727); Hattaway, Paul. Tibet: The Roof of the World (2021), 41.

- Peter Clarke, The Jesuits in Asia (Cambridge University Press, 1993), 204–207.

- Schmitz, Timo An Overview of Tibetan History, 91–92; Hattaway, 2021: 41–44.

- Hattaway, 2021: 68–71.

- Servin, Michael. “Christian Martyrs of Tibet.” Journal of Asian Church History 11 (2010): 23–39.

- Donald F. Lach, Asia in the Making of Europe, Vol. III (University of Chicago Press, 1977), 225–228.

- Holy See Press Office, “Relations between the Vatican and China,” L’Osservatore Romano, 2020.