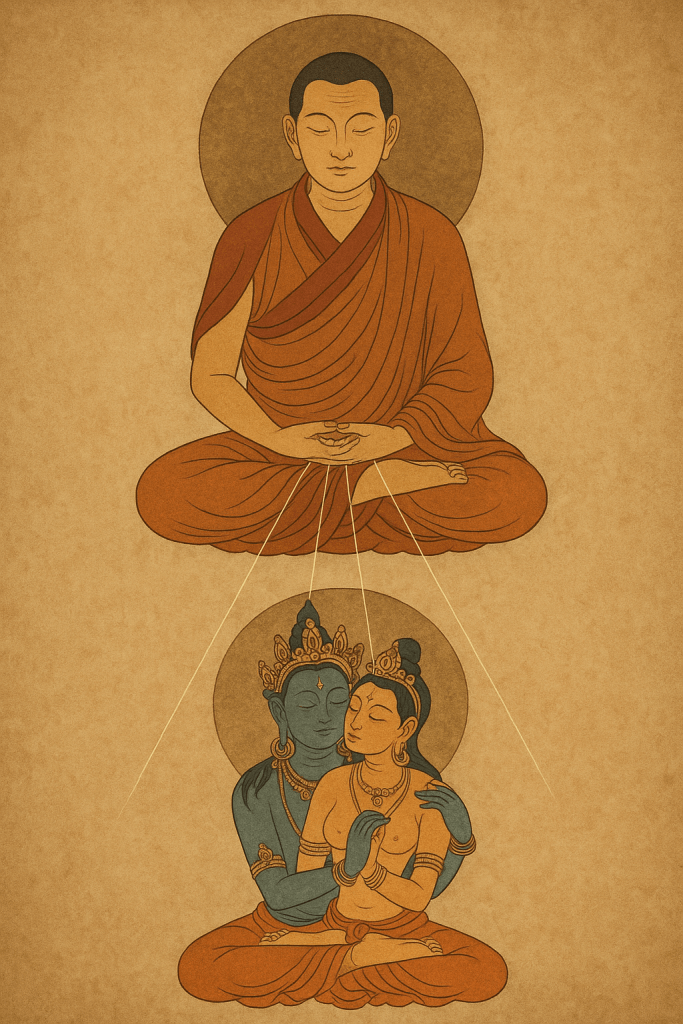

The ideal of tantric union in Vajrayāna Buddhism is described as the merging of wisdom and compassion, form and emptiness, masculine and feminine. In classical Tibetan art this appears as the yab-yum image of male and female deities in embrace.¹ The symbolism points to inner union, yet within the secrecy and hierarchy of tantra this ideal can become distorted. When intimacy, devotion, and power mix, the result can be psychological or sexual harm rather than awakening.

Union beyond the physical

“Union” (las kyi phyag rgya, maithuna) does not always refer to sexual intercourse. Many lineages teach “mental” or “energetic” union, where teacher and student visualize merging through subtle-body channels or shared deity practice.² Scholar Holly Gayley has examined how such “secret consort” (gsang yum) relationships blur lines between spiritual transmission and sexual exploitation.³

Anecdotal reports from practitioners describe non-physical experiences of sexual arousal or even orgasm initiated by the guru, without consent or understanding. For those unprepared, these experiences can feel like psychic invasion and an intrusion into the mind-body field. The ethical question is whether such experiences can ever be consensual in the context of absolute guru devotion.

The mechanism of “mental union”

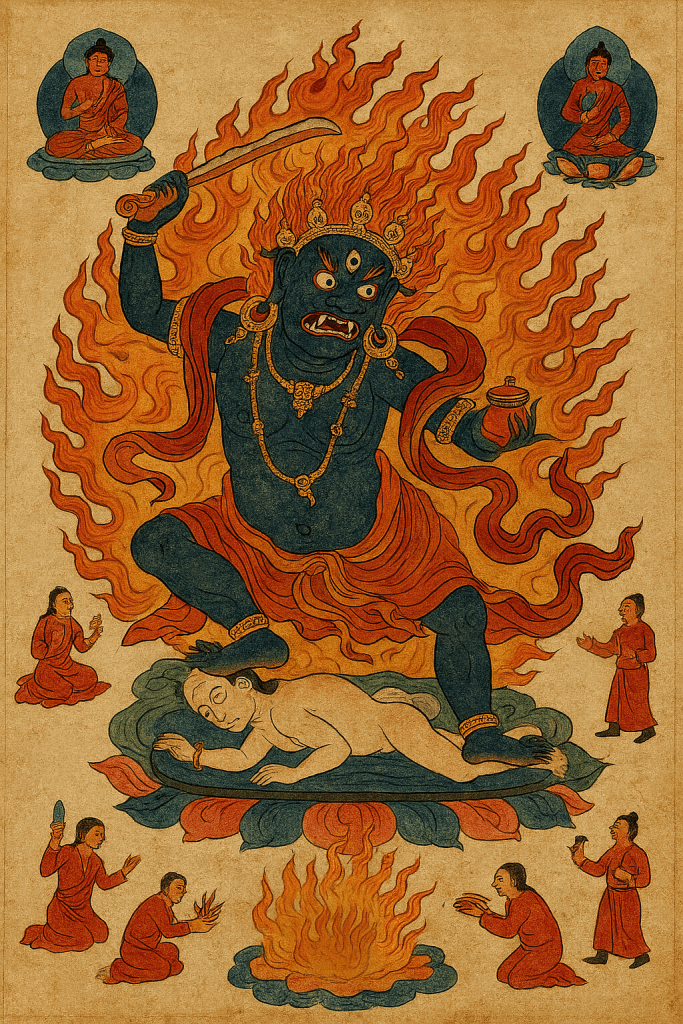

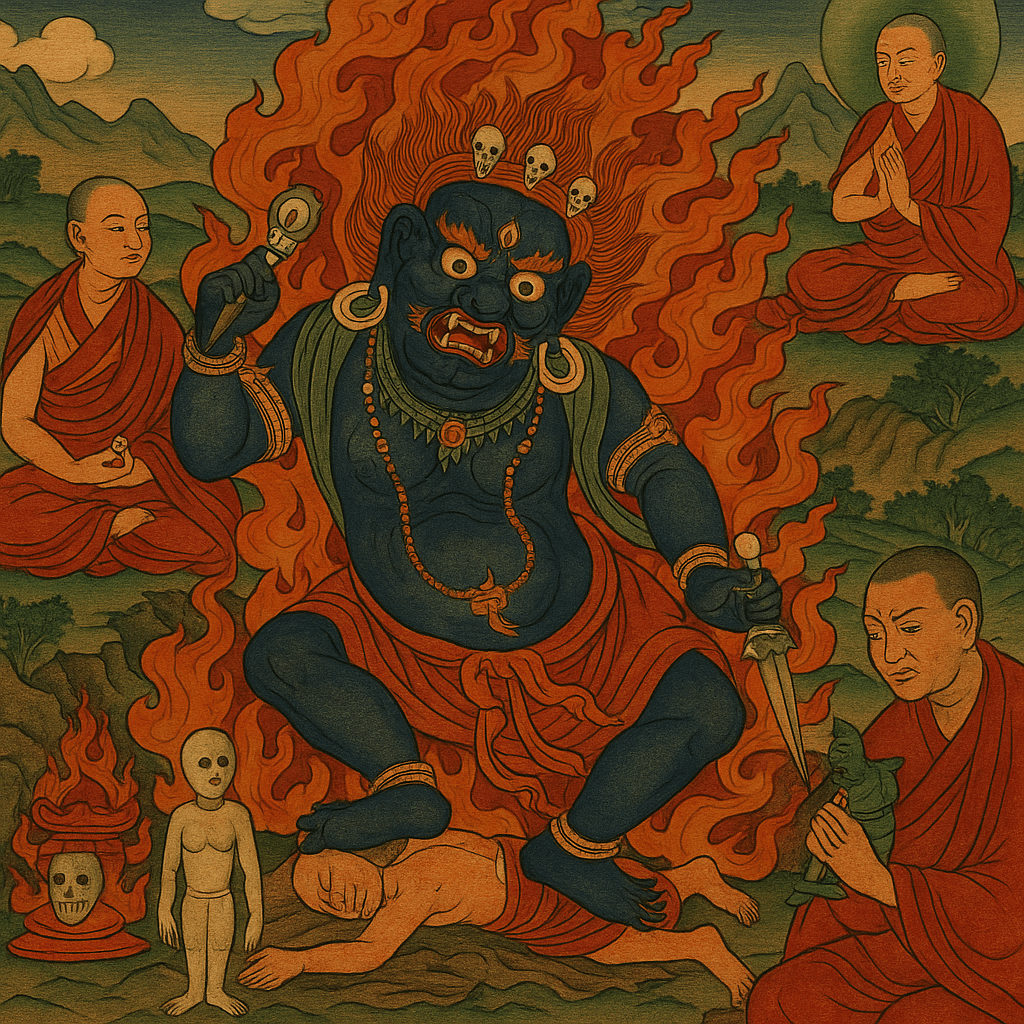

Tantric theory holds that through visualization, mantra, and subtle-body control, energies (prāṇa, rlung) can be directed between beings. A guru visualized as a deity may “enter” the disciple’s heart or crown chakra, merging mindstreams in blessing.⁴ In positive settings this symbolizes transmission of realization. Yet in cases of coercion the same mechanism becomes violation: the student’s energetic body is penetrated without consent.

Ritual texts sometimes describe the guru entering the disciple’s central channel (tsa uma) through gaze or mantra, symbolic of energetic or spiritual transmission.⁵ Within Hindu Tantra, similar accounts exist of masters manipulating the disciple’s kundalinī or chakras.⁶ These ideas frame the possibility of non-physical sexualized experiences as part of spiritual union. When combined with secrecy and unequal power, the result may feel like mental rape rather than initiation.

Power, secrecy, and consent

The Vajrayāna guru is regarded as embodiment of the awakened state itself.⁷ Devotion to such a figure can override ordinary ethical boundaries. In Western contexts, where students lack cultural preparation, the potential for abuse rises sharply. Alexander Berzin warns that Western practitioners often misunderstand the traditional checks on guru authority and therefore submit to unhealthy relationships.⁸

Secrecy deepens the problem. The samaya vow forbids disclosure of tantric practices, even to peers. Gayley observes that this secrecy “can be used to reinforce sexual violence and silence abuse.”³

Real-world allegations

At Kagyu Samye Ling monastery and its retreat centre on Holy Isle in Scotland, multiple allegations have surfaced over the past decade. Reports describe bullying and psychological pressure during advanced retreats. Recently it was reported that a British woman may have died by suicide after a four-month retreat there. While there is no public evidence of sexual misconduct toward her, other survivors have alleged earlier incidents of “energy access” by the same teacher. Allegations included the use of “subtle body rape/sexual energy invasion,” according to an article by Adele Tomlin on the Dakini Translations website.⁹

The under-discussed nature of subtle-body abuse

Such cases remain largely invisible because tantric language itself obscures boundaries between metaphor and reality. A teacher’s claim of “mind-union” or “blessing” can mask non-consensual psychic intrusion. Students are often told that doubt equals spiritual failure, and that refusal breaks samaya. Without transparent ethics, the very tools meant to free the mind become weapons of domination.

Moving forward

Ethical tantric practice requires explicit, informed consent at every level: physical, psychological, and energetic. Teachers must articulate clearly what practices entail, and students must retain the right to refuse and leave. The spiritual promise of union cannot excuse the violation of personal autonomy. However, this kind of transparency is unheard of. Proper review structures and support for survivors are practically non-existent in most Tibetan Buddhist centers. The allegations surrounding Samye Ling and Holy Isle highlight what scholars such as Gayley describe as tantra’s “shadow”: the ease with which power can transform spiritual intimacy into a form of manipulation and abuse.

References

- Buddha Weekly, “What’s a Consort Union in Tantric Buddhism?” https://buddhaweekly.com/whats-consort-union-tantric-buddhism-no-not-sexual-fantasies-psychology-yab-yum-consorts-union-wisdom-compassion/

- Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion, “Tantra and the Tantric Traditions of Hinduism and Buddhism.” 2016.

- Gayley, Holly. “Revisiting the ‘Secret Consort’ (gsang yum) in Tibetan Buddhism.” Religions 9 (2018).

- Snellgrove, David. The Hevajra Tantra: A Critical Study. Oxford University Press, 1959.

- Wedemeyer, Christian K. Making Sense of Tantric Buddhism: History, Semiology, and Transgression in the Indian Traditions of Buddhist Tantra. Columbia University Press, 2013, esp. chap. 3–4, on symbolic initiation and tantric ritual language.

- White, David Gordon. Kiss of the Yoginī: “Tantric Sex” in its South Asian Contexts. University of Chicago Press, 2003.

- “The Guru Question: The Crisis of Western Buddhism and Global Future.” Info-Buddhism.com.

- Berzin, Alexander. Relating to a Spiritual Teacher: Building a Healthy Relationship. Snow Lion, 2000.

- Dakini Translations, “Suicide of Woman Reported in ‘Survivors of Samye Ling Support Group,’” by Adele Tomlin, the sole author of that site. https://dakinitranslations.com/2025/10/28/suicide-of-woman-reported-in-survivors-of-samye-ling-support-group-alleged-bullying-by-drupon-khen-karma-lhabu-teacher-misuse-tantra/

- Buddhistdoor Global, “Maithuna: Reflections on the Sacred Tantric Union of Masculine and Feminine.” https://www.buddhistdoor.net/features/maithuna-reflections-on-the-sacred-tantric-union-of-masculine-and-feminine/