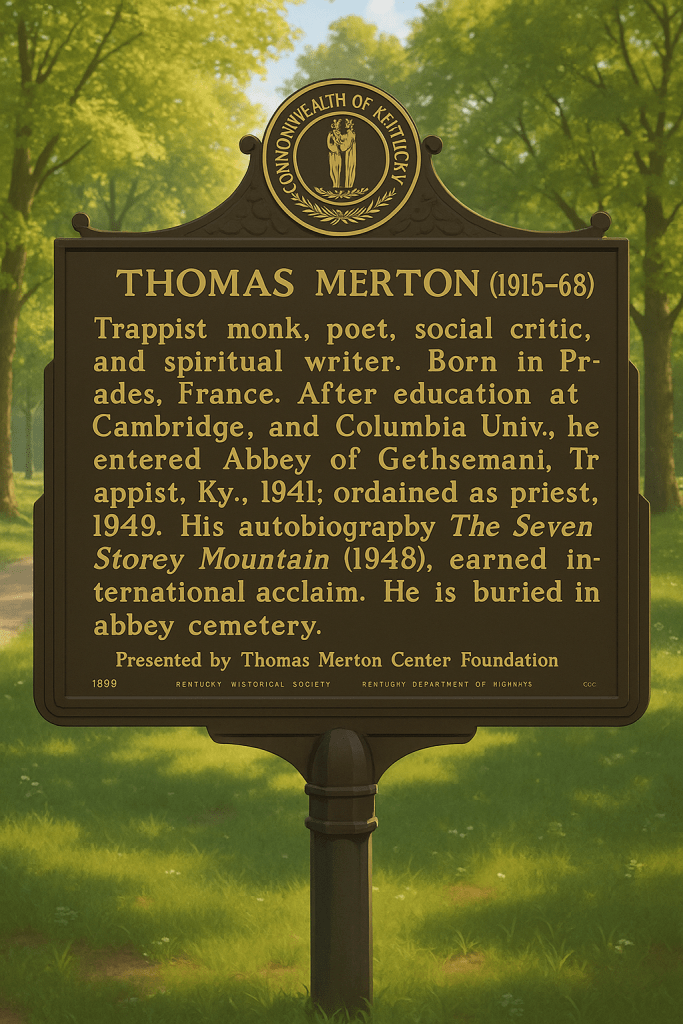

Thomas Merton remains one of the most fascinating and controversial figures in modern Catholic spirituality. A Trappist monk whose writing reached millions, he invited readers into a life of contemplation shaped by silence, inner stillness, and spiritual inquiry. By the 1960s, his search had expanded far beyond the borders of Christian tradition and into the world of Eastern mysticism. His journey raises important questions about discernment, authority, and the possibility that some mystical experiences do not come from God at all.

Why Merton looked East

Merton believed that Western Christianity had lost something essential. He felt that institutional concerns and intellectual debate had overshadowed direct experience of God. Eastern religions appeared to preserve a contemplative path in a purer form. Like many in the post–Vatican II era, he saw dialogue with non-Christian religions as an opportunity rather than a threat.

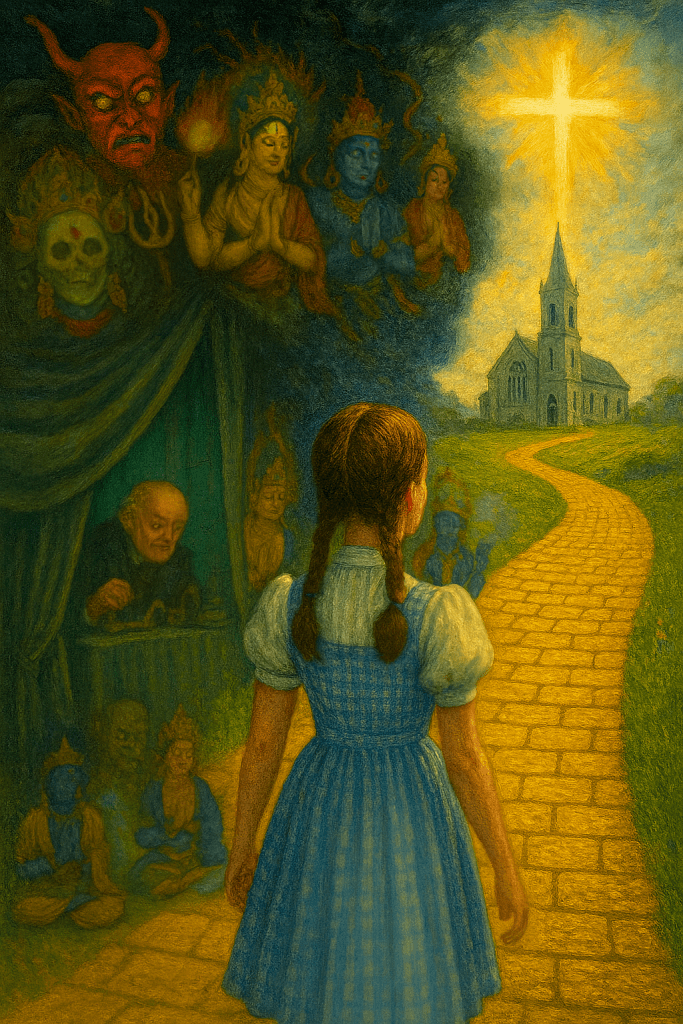

But such openness came with a cost. Many Catholics of his time assumed that all deep mystical traditions shared a common source. The idea that spiritual experiences could arise from contrary or even deceptive origins was rarely discussed. This lack of discernment created a vulnerable generation of seekers who treated Eastern practices as spiritually neutral when they were not.

Merton’s early interest in Asia

Long before traveling to Asia, Merton was reading Zen, Taoism, Advaita Vedanta, and Sufi mystics. He approached them with sincere curiosity, but also with a growing assumption that truth could be gleaned from any direction. His writings from this period suggest a desire for universal contemplative experience, sometimes without sufficient attention to the distinct theological and spiritual claims behind each tradition.

This tendency to universalize mystical experience would shape his final years.

Meeting the Dalai Lama

In 1968, Merton traveled to Dharamsala and spent several days with the Dalai Lama. Their meetings were warm and genuinely contemplative. Merton admired the Dalai Lama’s kindness, discipline, and clarity. The Dalai Lama later remembered Merton as the first Christian monk who came to him not as a tourist or academic but as a fellow practitioner of deep prayer.

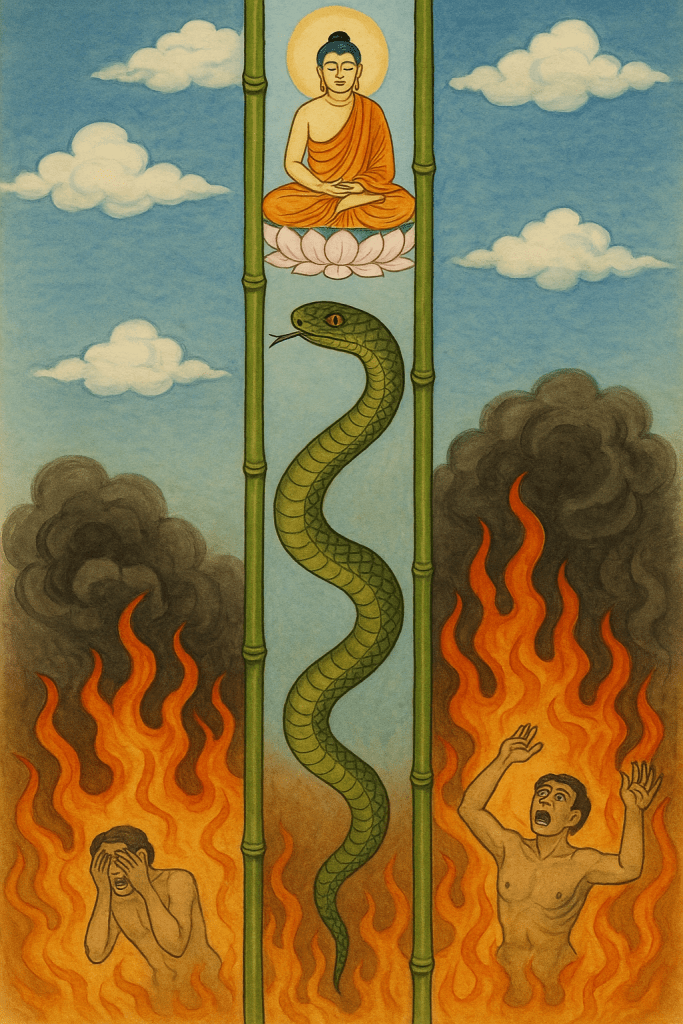

Yet admiration does not erase theological differences. Tibetan Buddhism denies a creator God, embraces reincarnation, and employs esoteric tantric practices that involve deities outside the Holy Trinity. From a Christian point of view, this difference is huge. The Church has long taught the discernment of spirits: mystical experiences must be tested, because deceptive spiritual forces can imitate peace, clarity, and even compassion. Merton did not always express this caution.

Encounter with Kalu Rinpoche

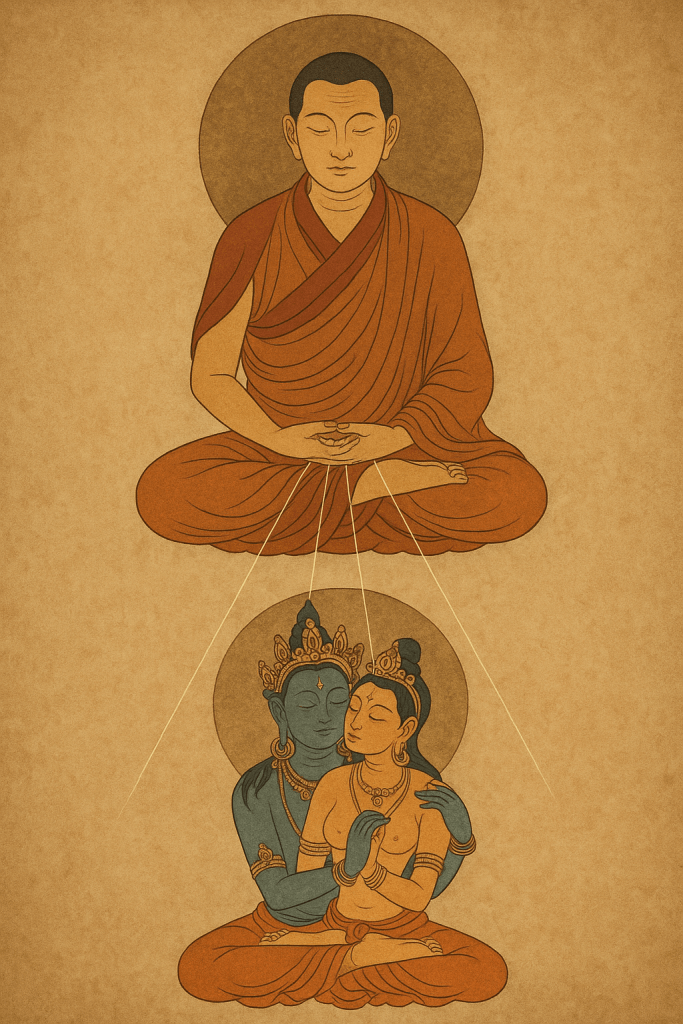

Merton also met Kalu Rinpoche, one of the most respected Tibetan meditation masters of the twentieth century. He attended teachings on Mahamudra and was deeply impressed by the monastic discipline he witnessed. Kalu Rinpoche even invited him to undertake a long hermit retreat. Merton seemed drawn to the idea.

But Tibetan Buddhism contains layers of esoteric practice that Merton, like most Westerners of his time, did not fully understand. The serene exterior of Tibetan spirituality often conceals tantric rituals, spirit invocation, and hierarchical guru devotion that are fundamentally incompatible with Christianity. Later revelations of abuse and occult manipulation inside some of the major Tibetan lineages show how incomplete the Western picture had been. Merton could not have known this, yet his enthusiasm reflected a lack of discernment that would affect many who followed in his footsteps.

What else he explored

Merton’s range of interests was broad. He read Zen masters, Taoist sages, Hindu philosophers, and Sufi poets. He studied Christian hesychasm with new energy and sought common threads among all traditions. His impulse was generous, but generosity is not the same as spiritual clarity. Christian prayer directs the soul toward union with God. Eastern meditation, especially tantra, aims at dissolving the ego and merging with non-Christian spiritual entities.

These are not complementary goals but representative of different spiritual destinies.

Bangkok and a mysterious death

After leaving Dharamsala, Merton traveled to Bangkok to speak at an international monastic conference. On December 10, 1968, he died in his cottage shortly after giving a lecture. The official explanation was accidental electrocution from a faulty fan. Yet no autopsy was performed, and the circumstances were poorly documented. The inconsistencies have fueled speculation for decades.

His death came at a moment when he was moving more deeply into Buddhist thought. Whether he intended to integrate aspects of Tibetan practice into Christian monasticism remains unknown. His passing has an unfinished quality, as if he was on the edge of a major spiritual shift whose implications were never tested.

Why Merton still matters

Merton’s life challenges readers to seek authentic spiritual contemplation, not just intellectual understanding. It also warns Christians that not every path that promises depth is aligned with God. Eastern systems often carry metaphysical commitments and spiritual forces that stand in real conflict with Christian revelation. Without a strong framework of discernment, even sincere seekers can be misled.

Merton’s writings still inspire, yet his story also stands as a cautionary tale. The longing for mystical experience is real and often holy, but it must be shaped by sound doctrine and a sober awareness that not every spiritual path leads toward God.