What if some of the radiant beings that ancient texts call Seraphim, the fiery, serpentine angels who once circled the throne of God, fell from that high order? The Hebrew word saraph itself means both burning one and serpent. In that ambiguity lies a bridge between the flaming spirits of heaven and the serpent powers found in other traditions.

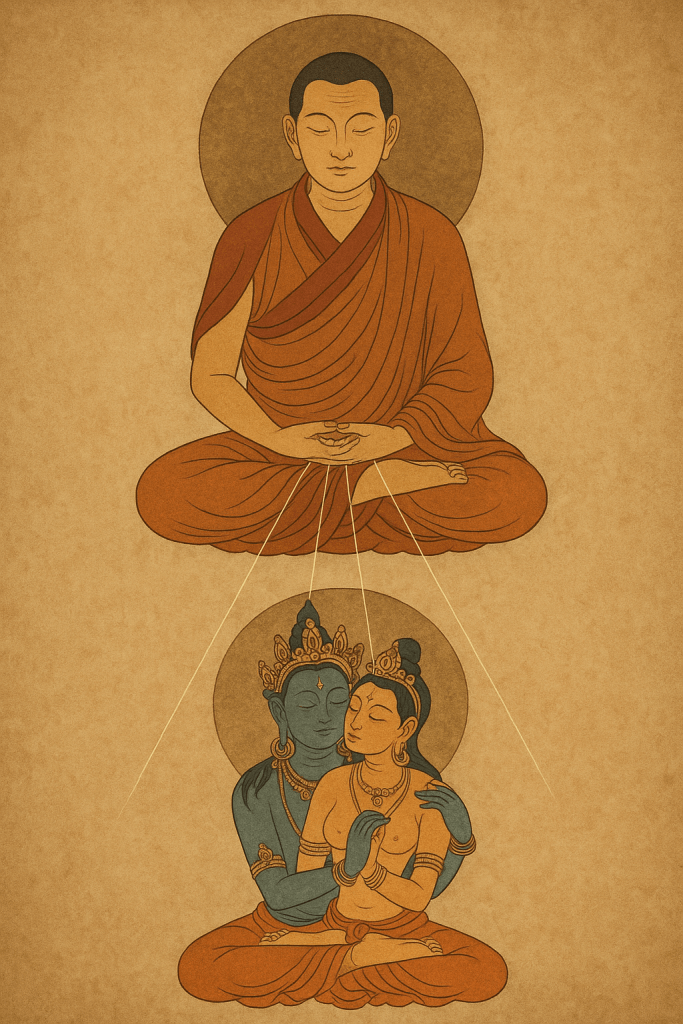

Across the world, in the Sanskrit Purāṇas and yogic literature, there are also serpentine intelligences: the Nāgas, the Kundalinī energy, and the goddess figures who appear surrounded by flames. The sage Patañjali, author of the Yoga Sūtras, is deeply linked with serpent symbolism. In Indian mythology, he is sometimes described as an incarnation (avatāra) of the serpent deity Ādiśeṣa, or Ananta, the cosmic serpent who supports Viṣṇu. Ādiśeṣa is said to have descended to earth to bring knowledge that would relieve human suffering. This connection is why Patañjali is often portrayed with a serpent hood behind his head or a serpent body below the waist. Whether or not serpent spirits literally whispered the Yoga Sūtras to him, serpent imagery pervades yogic and tantric cosmology. The Nāgas are keepers of divine wisdom, and Kundalinī is envisioned as a coiled fiery energy at the base of the spine that awakens through disciplined practice. Over time, these motifs merged into a vision of serpentine power as both the source and the path of revelation. Suppose these mythic beings were echoes of the same order of spirits, glimpsed through another cultural lens. If the Seraphim of the Old Testament were “burning ones,” what would a fallen Seraph look like to those who encountered its power? Perhaps like the Kundalinī Śakti, a current of fire roaring through the body, consuming and transformative, perilous and hideous.

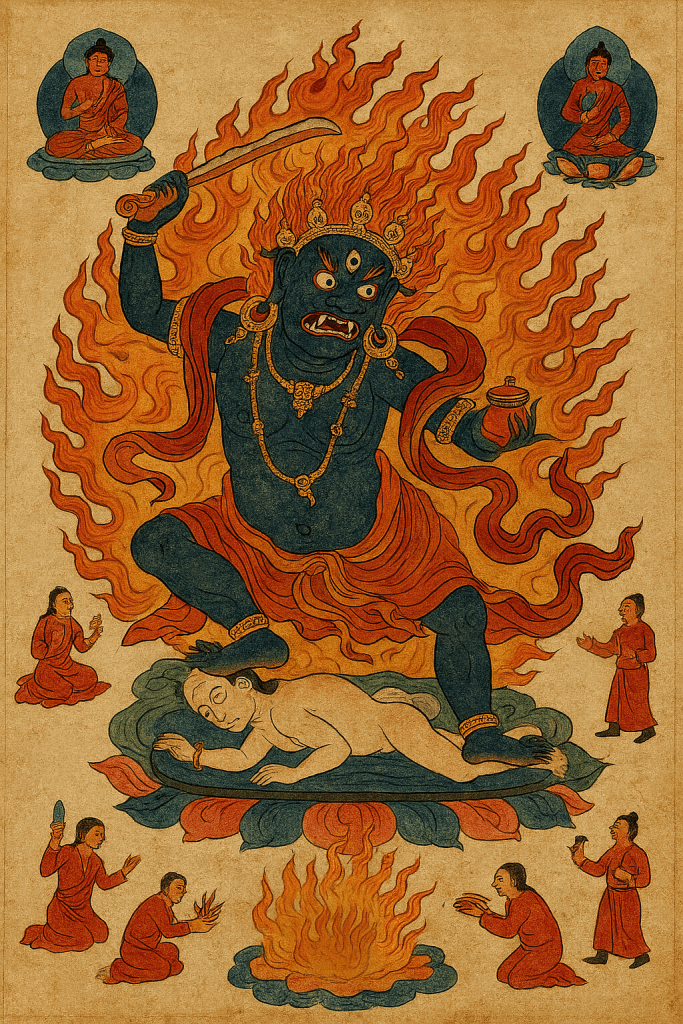

In Tibetan tantric art, figures such as Vajrayoginī blaze with this same imagery. She stands wreathed in flame, hair flying, a garland of human heads around her neck: a being of immense energy and occult knowledge. To her accomplished devotees she is enlightenment embodied, but to others overwhelmed by her force, the experience could resemble an encounter with a terrifying, cosmic intelligence that feels at once divine and frightfully destructive.

In Christian cosmology, the Seraphim stood closest to the divine light, their essence described as pure burning love. If the story of the angelic rebellion is true, the fall of Lucifer and his host might be understood as the perversion of that love for God turned inward toward self-worship. The Seraphs, if any joined that rebellion, would have fallen from the highest heaven to earth yet carried the memory of their incandescent proximity to the Most High. After such a fall, their nature would remain fiery but unmoored, no longer worshipping the divine but seeking vessels in which to become divine objects themselves, demanding reverence rather than giving it. Their rebellion took the form of imitation, of becoming godlike and leading humans away from God through elaborate systems of spiritual artifice. Seen through that lens, the serpent fire that rises in the body could be a vestige of this celestial descent, a remnant of the same luminous essence striving to return upward yet incapable of abiding in heaven because of their grave sin. In mythic terms, these fallen Seraphs might not have become the grotesque demons described by some exorcists but radiant, fallen intelligences deprived of their proper axis.

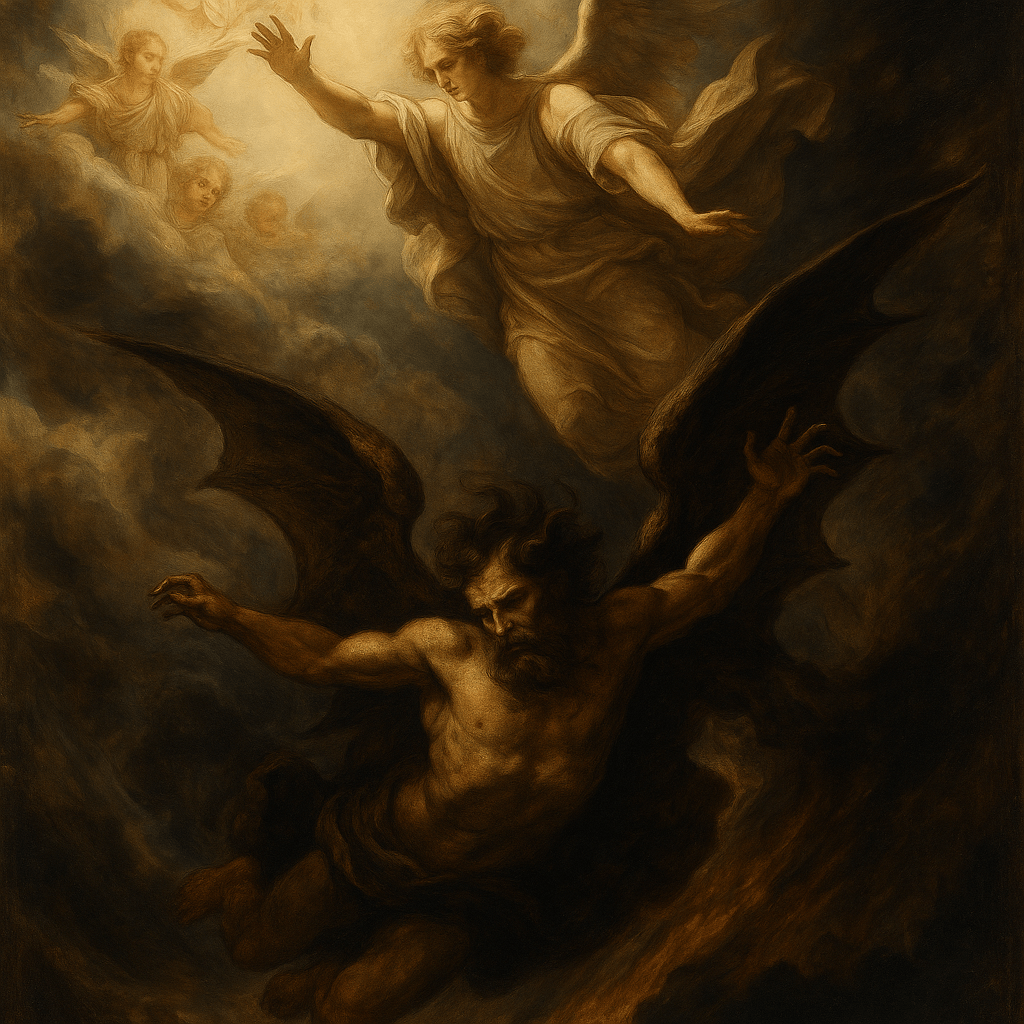

Catholic exorcists often describe demons as denizens of hell, creatures of stench, mockery, and degradation that feed on blood and fear. Yet if a third of the angels fell, the fallen host was not of one kind alone. Tradition holds that beings from all nine choirs joined the rebellion, from the lowly messengers to the highest Seraphs who once blazed before the throne. After the fall, these spirits lost their divine orientation but not their essential nature: fiery where they had been fiery, clever where they had been wise. In rebellion they became hierarchies of distortion, a dark mirror of heaven. Some manifest as the grotesque forms exorcists encounter; others as subtler intelligences still bearing the trace of their former luminosity. And what of the Nephilim, the offspring of the “sons of God” and human women? When they died, it is said, they became wandering spirits of great malice. “Demon,” then, is not a single species but a spectrum of fallen orders, each expressing what it once was in a corrupted form. As one exorcist observed, each fallen angel is a species unto itself. A fallen Seraph would perhaps appear differently from a fallen Power, Dominion, or Nephilim spirit.

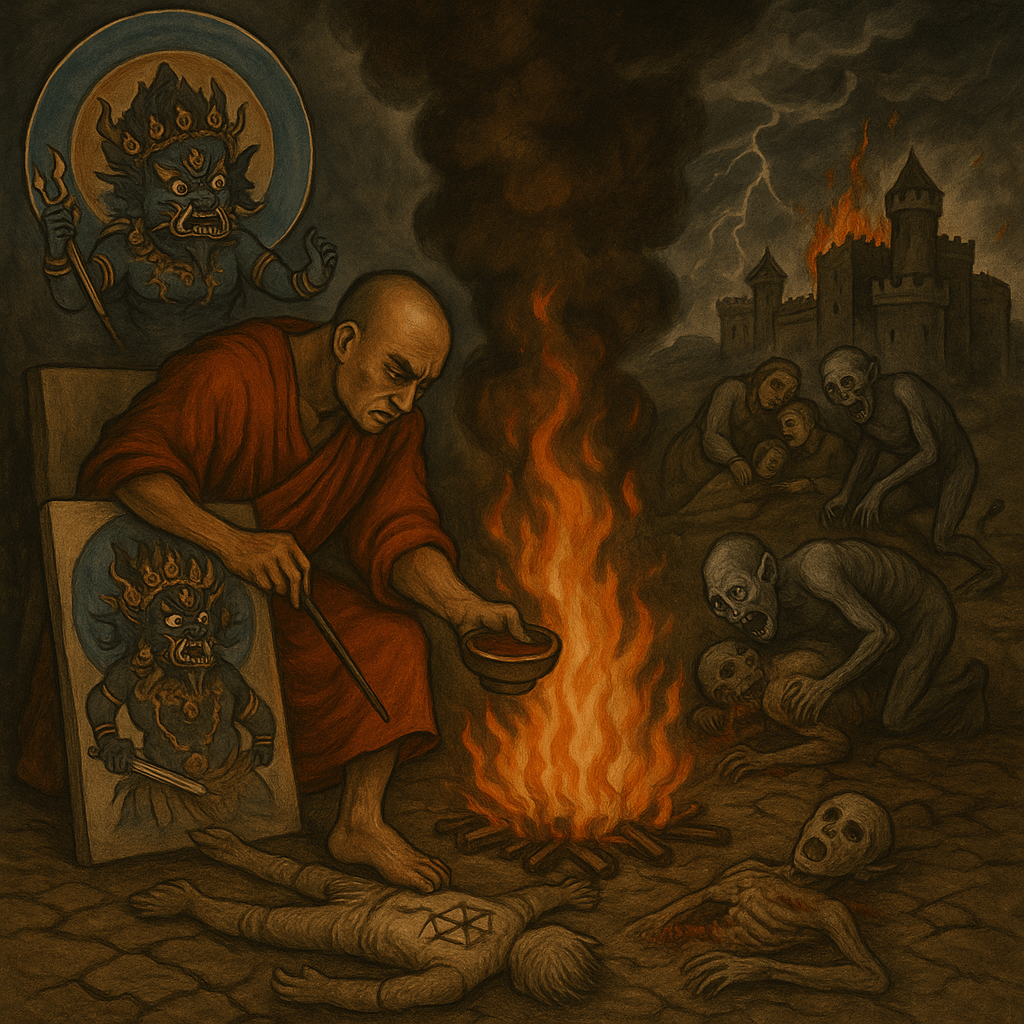

If the Kundalinī or tantric fire represents contact with that residual Seraphic current, it may explain why it bears both a luminous and a destructive face. The energy feels ancient and intelligent. The ecstatic experiences described in yogic ascent mirror, in certain sense, a fallen entity yearning to return to its source. The agony that often accompanies a kundalini awakening—the painful burning, the psychic rupture, and the sense of another will within—could be the friction between that powerful celestial energy and the humble human vessel struggling to contain it. Whether one interprets this as possession or not, the pattern remains: what was once angelic becomes dangerous when severed from its orientation toward God and seeking to inhabit a human host.

Whether understood theologically, psychologically, or experientially, the speculation remains: serpent fire is something that seeks to burn within human beings, hoping to be redeemed and adored rather than condemned.

Spiritual paths that promise transcendence through serpent fire often walk a razor’s edge where illumination meets peril. Tantric Deception seeks to explore that tension, showing how practices that seem to lead toward light may instead open gateways into spiritual posession and darkness. What begins as ascent toward divinity can turn into descent into hell, both in this life and beyond. To approach the serpent fire is to confront both heaven and the echo of its fall, a perilous imitation of grace. One might call it a race to the bottom. The fallen angels made their choice long ago, and according to Christian theology there is no return for them. Those who follow, worship, or seek to become like them will share their fate in the same fire reserved for their fallen gods, a place described in Scripture as the final dwelling of the devil, his angels, and all who reject the true light. There they are said to be cast into a lake of fire that burns without end, cut off forever from the presence of the Most High God, where the torment born of rebellion becomes eternal.