The United States was founded as a nation with Christian underpinnings. Though explicitly rejecting a state church, the culture, law, and moral sensibilities of the early colonies were undeniably rooted in European Christianity. The Puritans brought Calvinism to New England, Anglicans established themselves in the South, and Catholic missions flourished in Spanish-controlled territories such as California and the Southwest. Later waves of immigration brought Lutherans, Methodists, Presbyterians, and Baptists who carved out religious strongholds across the Midwest and South.

By the 19th century, the so-called “Bible Belt” had emerged in the South, Methodism had spread explosively through revivalism, and Catholicism had grown with Irish and Italian immigration. By the mid-20th century, America was demographically and culturally a Christian nation. According to Gallup polls from the late 1950s and early 1960s, more than 90% of Americans identified as Christian, with the largest groups being Protestants (roughly 70%) and Catholics (about 25%).

The Cultural Explosion of the 1960s

Then came the 1960s, a decade that tore through old structures. The Vietnam War, the civil rights struggle, the sexual revolution, psychedelic experimentation, and anti-establishment sentiment all converged. The cultural consensus rooted in old forms of Christianity began to fracture. Simultaneously, the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965) radically reformed Catholicism, introducing liturgical changes, opening the Church to interreligious dialogue, and softening the rigid boundaries between Catholic identity and “the other.” For the first time in history, the Catholic Church officially entertained the possibility that truth could exist outside its walls. This, in turn, prepared the ground for interfaith openness and even syncretism.

At the same time, young Americans disillusioned by the war machine were searching for new sources of peace and meaning. Buddhism, with its emphasis on compassion, nonviolence, and meditation, arrived at exactly the right moment. For the counterculture, it offered a path to peace and love in stark contrast to the devastation of the Vietnam War.

Gurus, Lamas, and the Tibetan Diaspora

The timing was uncanny. In 1959, Tibet fell to the Chinese Communist takeover, and a vast exodus of Tibetans fled into India and Nepal. Among the refugees were lamas who carried tantric teachings preserved for centuries in their monasteries. In the late 1960s and 1970s, the first wave of Western seekers, hippies from the US and Europe, traveled to India and Nepal, encountering these masters in exile. For the Tibetans, these were years of profound trauma, dislocation, and cultural upheaval. For the Westerners, it was a spiritual gold rush.

Out of this strange meeting of East and West emerged the first Tibetan Buddhist centers in America. By the mid-1970s, figures such as Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche and the 16th Karmapa had established institutions across the country, often structured exactly like churches: religious nonprofits with tax-exempt status, complete with community rituals, hierarchies, and devotional practices. The Dalai Lama’s influence would come slightly later, after his first U.S. visit in 1979. Scores of young Americans, many from Christian families, converted to Tibetan Buddhism, convinced they had found something far superior to the “hollow faith” of their parents.

The Hidden Face of Tantra

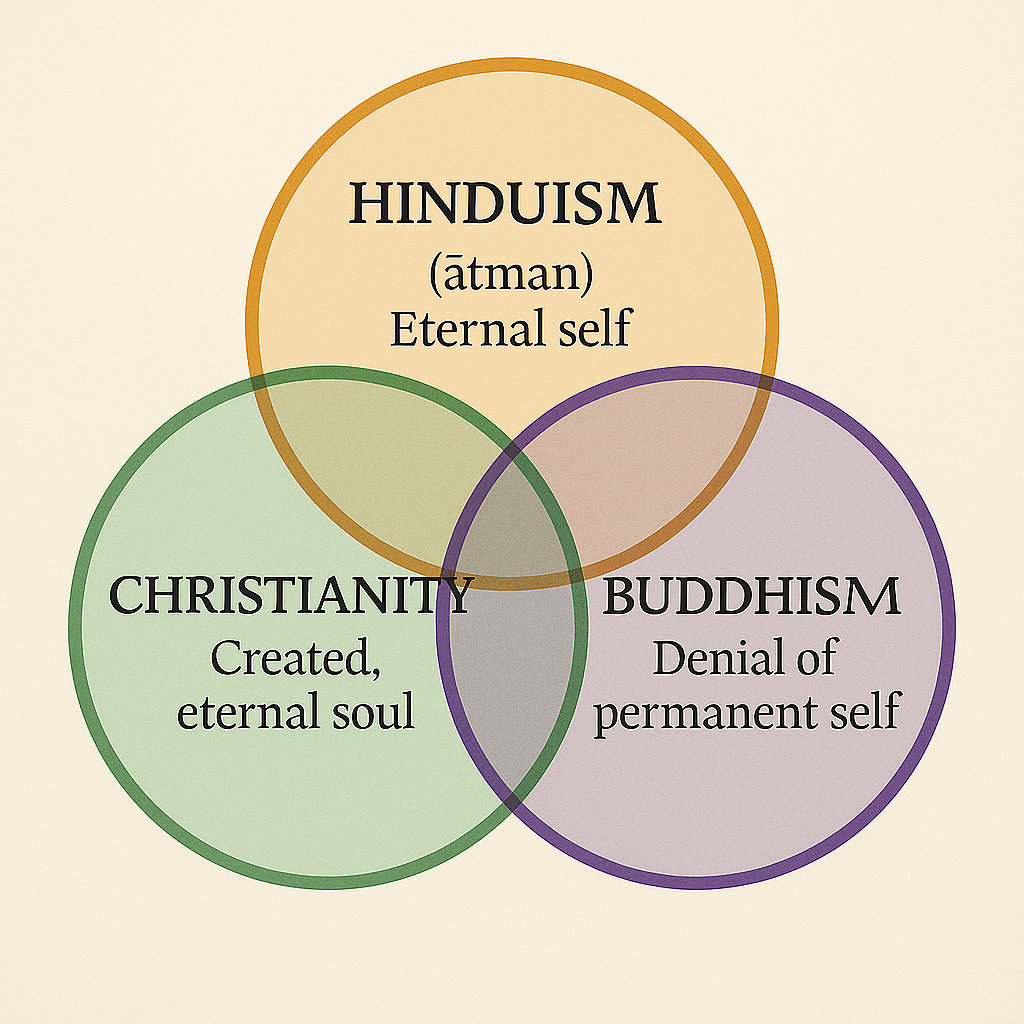

Buddhism, in its ethical and philosophical dimensions, does indeed share much with Christianity such as compassion, ethical restraint, and renunciation of greed and hatred. But hidden within the Tibetan stream lies tantra, a system of occult practices and magical invocations that have no basis in the teachings of the historical Buddha. Instead, they represent a grafting of Indian tantric traditions onto Buddhism. Tibetan shamanic practices were also woven into the mix—rituals of spirit invocation and magical rites—which only reinforced the occult dimension and pushed the system even further from the teachings of the historical Buddha.

Some early Tibetan teachers in the West even made cryptic statements hinting at the true nature of their teachings. One unsettling quote, difficult to substantiate, yet chilling in its cynicism, was attributed to a Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhist master: “Satan is Vajra Jesus.” Indeed, after decades of immersion, it became clear to me that “Vajra” is not merely a symbol of indestructibility as is taught, but a coded reference to occult power, Satanic at its core. The genius of the system lies in its camouflage: cloaked in the ethics of Buddhism, the darker currents of tantra flow undetected.

Tibetan Buddhism and Freemasonry: A Parallel

The comparison with Freemasonry is instructive. Many of America’s Founding Fathers were Freemasons, and while the fraternity appeared on the surface to be a benevolent society, its higher degrees revealed allegiance to Lucifer.* At the lower levels, members encountered moral lessons and fraternity; only later, through oaths and initiations, was the deeper reality disclosed.**

Tibetan Buddhism operates in a strikingly similar way. Entry-level students learn meditation, ethics, and compassion. Only after deeper commitment, vows, and initiations are they gradually exposed to tantric practices: rituals involving wrathful deities, consorts, and occult visualizations. By then, they are bound by vows and loyalty to their teachers.

Full Circle: From Freemason Roots to Tantric Fruits

In this light, the embrace of Tibetan Buddhism in America seems less like an alien import and more like a continuation of an esoteric undercurrent already present in the nation’s DNA. The United States, born with strong Christian roots but also intertwined with Freemasonic structures, has become fertile ground for tantric infiltration. Just as Freemasonry concealed its Luciferian essence under a philanthropic veneer, Tibetan Buddhism cloaks its demonic core under Buddhist compassion.

The cultural revolution of the 1960s cracked open the shell of Christianity in America. Into that breach poured the lamas and their tantric systems. What appeared to be a message of peace and healing, at precisely the moment of American disillusionment, carried with it an occult agenda. In that sense, the story of tantra in America is not just about East meeting West, but about a deeper pattern repeating itself: a hidden, Luciferian tradition resurfacing under new guises.

*Not every Freemason engages in satanic practices, or even knows about that aspect of it. It is only at the 33rd degree and beyond that initiates are allegedly confronted with a Luciferian element. This is somewhat like the staged vows and initiations of Tibetan Buddhism that lead beyond basic Buddhism into communion with a pantheon of tantric gods that are not merely symbols or archetypes. Each level of Freemasonry opens the way to higher oaths and allegiances, ultimately directed toward Lucifer and other demons.

**While many of the Founding Fathers were Freemasons, probably some of them really did have noble intentions and wanted to make Washington, D.C. a kind of beacon of light. But there were very deep, dark, hidden forces that lurked within Freemasonry.