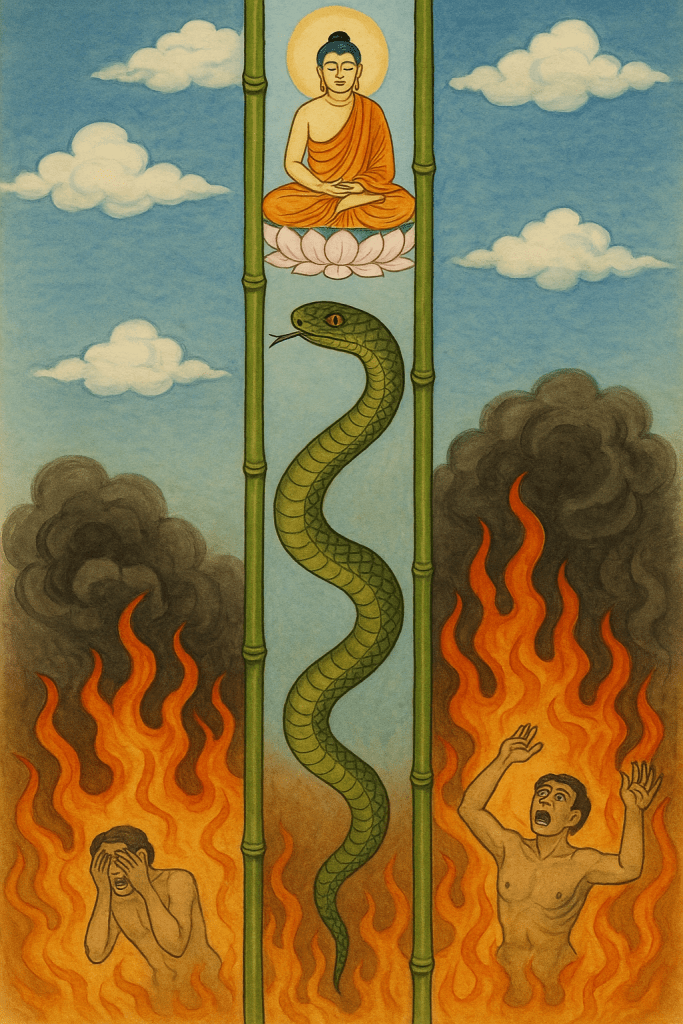

In Tibetan tantric Buddhism, the image of the snake trapped in a bamboo tube is more than a vivid proverb. It functions as a doctrinal warning: once a student enters the tantric path, there is no lateral escape. One either goes upward toward awakening or downward toward failure and “vajra hell.” Teachers have used this image to describe the uncompromising nature of samaya, the vows that bind a student to the guru, the deity, and the tantric methods themselves.¹

What is striking is how explicitly the tradition frames tantra as irreversible and high-stakes, and how rarely that stark truth is communicated to Western beginners before they agree to the vows that supposedly make the tube snap shut behind them. This mismatch between traditional warning and Western presentation is not a minor detail; it shapes the entire experience of Vajrayāna in modern contexts.

When the Warning Arrives Too Late

Many longtime practitioners have reported that the “snake in the tube” metaphor is introduced only after they have taken empowerments, established loyalty to the teacher, and accepted vows they did not fully understand. In one account, students were told after receiving advanced teachings that they were now like snakes [in a tube] with no side exit, and that questioning or leaving the guru’s authority carried dire karmic consequences.² Once framed in these terms, the student is no longer encountering tantra freely. The imagery becomes a retrospective justification for total commitment and an interpretive trap that discourages reevaluation, dissent or disengagement.

This sequencing matters. Warnings given after the student is already inside the tube are not warnings at all; they function as a mechanism of control. Sadly, it’s not just empty scaremongering to get the student to do whatever the teacher wants. The teacher can play a part in destroying the student if he wishes.

Western students, however, often enter tantra without the cultural framework that understands concepts like vajra–hell, and as a result frequently interpret them metaphorically or ignore them altogether during empowerments or teachings. As a result, the gravity of samaya is often hidden in plain sight. Students may assume that vows are symbolic or aspirational when, within the tradition, they are treated as binding conditions that determine spiritual destiny.

The asymmetry of information here is profound. Tibetan teachers know the stakes, but Western students usually do not.

Fear as a Reinforcing Mechanism

Inside the tantric system, samaya is often discussed as a bond of trust and devotion. But its shadow side is rarely addressed openly: the way threats of karmic ruin can be used to enforce silence and obedience. If leaving the guru, criticizing harmful behavior, or even doubting the teacher’s purity is framed as a breach of samaya, then fear becomes central to the student’s experience. Some Tibetan masters teach that both teacher and student can fall into vajra-hell for damaging the guru-disciple bond.³ In practice, however, this warning is most often directed at students, who are told that speaking publicly about misconduct or abuse may destroy their spiritual future.

Why the Snake Matters

The “snake in the bamboo tube” metaphor distills these concerns with unusual clarity. It shows that tantra is not designed to allow experimentation or partial commitment. It requires total participation in a closed system with its own rules, hierarchies, and cosmology. In cultures where this system has historically been embedded, those entering it do so in fuller awareness of the stakes. In the West, students often do not and they may hear such warnings in a highly suggestible state, without really grasping the implications.

One famous guru in the 1980s bluntly told students that they could be both Christian and Buddhist with no conflict whatsoever. This blatantly goes against Christian teaching. In those days Westerners were often thrust into the three-year-retreat program shortly after they signed up for teachings at Dharma centers with no knowledge of what they were really getting into. Many had little preparation to truly understand the arcane nature of samaya and its risks. Furthermore, many Tibetan teachers took advantage of their roles as authority figures to manipulate vulnerable students into sexual relationships and other sorts of commitments. Engaging in secretive sexual relationships with students while pressuring them to take highest yoga tantra vows and practices that would bind them forever often led to deep confusion and psychological unmooring.

The result is a form of spiritual engagement that looks consensual on the surface but lacks true informed consent. Students may be drawn in by promises of transformation but only later discover the rigidity of the commitments they have made. This is especially jarring given that Vajrayāna wraps together the renunciation of the Hinayāna, the boundless compassion of the Mahāyāna, and the esoteric demands of tantra. In this unwieldy fusion, the same tradition that teaches gentle observation of thoughts can also insist that a single critical thought toward one’s guru carries the weight of karmic catastrophe. The threat of vajra-hell sits uneasily beside Buddhism’s wider emphasis on compassion and non-judgment. An ethical issue looms large: a path that describes itself as having no side exit should not be offered as if it does.

To treat tantra’s danger as a secret or secondary detail is to undermine the integrity of the path itself. If practitioners are indeed snakes in a tube, they deserve to be told before they go inside.

Footnotes

¹ “Once you take samaya you become like a snake in a vertical bamboo tube: you’re either going up, or you’re going down. You can’t sneak out the side.” (Kun zang.org) (kunzang.org)

² Note: practitioner-reports and forum posts indicate the metaphor is often applied post-initiation. For example: “A Vajrayana practitioner is like a snake in a tube; … he can either go up or down, not left or right.” (dharmawheel.net)

³ “The metaphor for samaya is a snake in a bamboo tube. It has only 2 directions – up to enlightenment or down to the hells.” (TibetDharma.com) (Tibetan Buddhism)