The descent into Bengal began with a vision. As our plane banked low over the hazy sprawl of Calcutta, I sat in meditation, quietly preparing for a long journey north to Sikkim for a series of tantric empowerments. Then, quite suddenly, a naked dakini appeared before me, dancing and beckoning. She seemed to be greeting me to Calcutta. I knew, or thought I knew, that it was Kali.

We stayed in a modest Baptist guesthouse chosen for its safety and low price, a short walk from Mother Teresa’s compound. It was late October, and the air was warm and humid. Calcutta felt down at heel, yet intellectual and dignified. My companions, all Tibetan Buddhist practitioners, decided to visit Mother Teresa’s place to pay homage. I hung back. They were sincere in their devotion to that famous nun, but something in me pulled in another direction. Although I had been raised Catholic, I felt a faint aversion to anything connected with the Catholic Church. I regarded the religion as problematic at that time. Still, seeing how genuinely excited my friends were, I encouraged them to go.

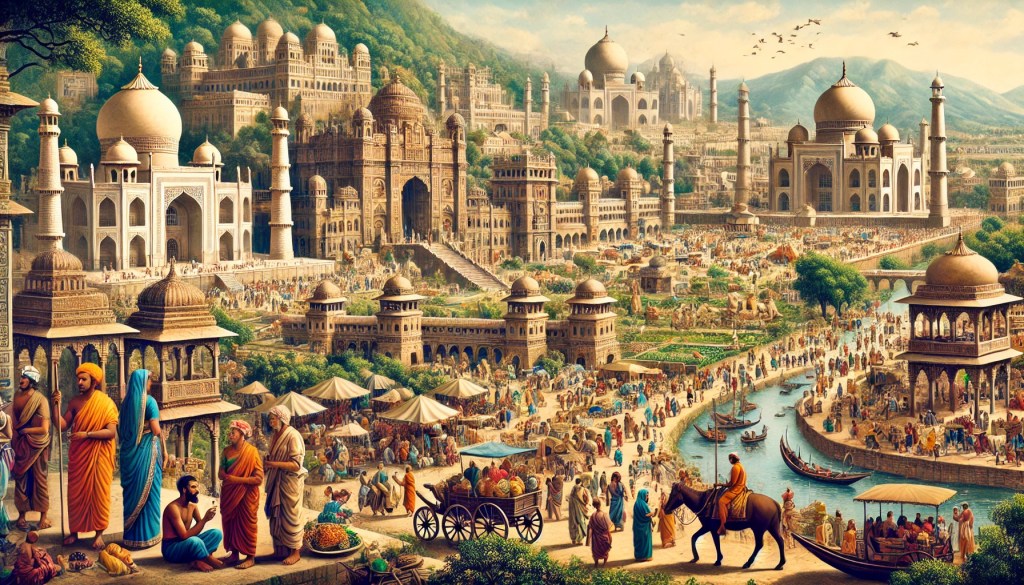

The next day I hired a taxi and arranged for us to cross the city to the Dakshineswar Kali Temple, the same temple where Ramakrishna had worshipped and experienced his visions of the Divine Mother and became enlightened. “We really must make the effort to see it,” I told the others, although I wasn’t sure why. The journey took nearly an hour through dusty streets and chaotic traffic. I had read that Kali was the patron goddess of Bengal, and that Dakshineswar was one of her most important shrines. The closer we came, the stronger the pull felt.

At the temple, a long line of Indian devotees wound through the courtyard, each waiting to glimpse the goddess and receive her blessing. We appeared to be the only Westerners there. I knew very little about the history of the temple at that point. All I knew was that I had always been intrigued by Ramakrishna among all the Hindu mystics and had always wanted to visit his temple and pay my respects.

The Temple and Its History

The Dakshineswar Kali Temple was founded in the mid-nineteenth century by Rani Rashmoni, a wealthy zamindar who, according to legend, dreamt that the goddess Kali commanded her to build a temple on the banks of the Hooghly River rather than journey by boat to Varanasi¹. Rashmoni had been preparing for the pilgrimage for months and had spent a small fortune, but on the night before her departure, Kali appeared in a dream and told her she need not travel at all. Instead, the goddess instructed her to raise a temple and enshrine an image that Kali herself would inhabit, blessing all who came to worship. The temple was completed in 1855 and the complex stands on land said to resemble a tortoise, a form considered especially auspicious in Shakta-Tantra cosmology².

Architecturally, the main temple is built in the navaratna (nine-spired) style typical of Bengal, raised on a high platform overlooking the river³. Surrounding the sanctum are twelve identical Shiva shrines aligned along the Hooghly’s edge, a small Radha-Krishna temple, and bathing ghats for pilgrims⁴.

Inside the sanctum resides Bhavatarini, a fierce aspect of Kali known as “Saviour of the Universe,” depicted with one foot on Shiva’s chest⁵. The mystic Ramakrishna served as the temple’s priest and carried out years of intense spiritual practice within its grounds, transforming the site into one of India’s holiest centers of Shakti worship⁶. The atmosphere is thick with incense, bells, flowers, and the hum of a thousand mantras. Once inside the gate you feel the city’s chaos fall away.

As we stood in line, something unexpected happened. An Indian guard suddenly appeared, motioned to me and a Buddhist friend, and beckoned us forward. Without explanation, we were led past the waiting crowd directly to the inner sanctum. The goddess stood before us, draped in red and gold, eyes alive in the flicker of ghee lamps. When I received prasad, it tasted sweet and delicious, and I felt a surge of a deep, penetrating love. It was so overwhelming that I began to cry.

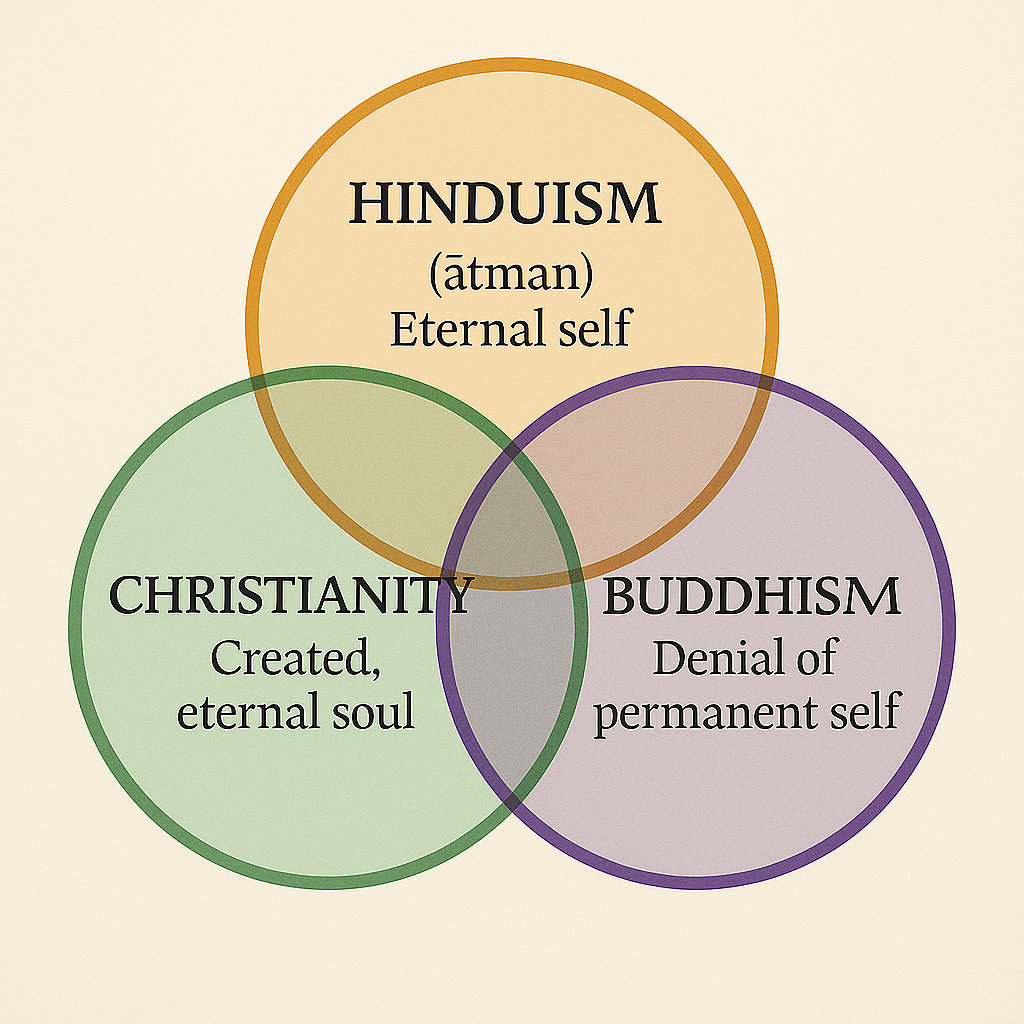

As a Tibetan Buddhist, I had always regarded Hindu deities as somehow inferior and secondary to the Tibetan ones who were the representations of the ultimate truth. My practice had centered on Vajrayogini and Chakrasamvara, not on Kali. Yet there, when the experience of divine love engulfed me in the Dakshineswar temple, I felt an unmistakable recognition.

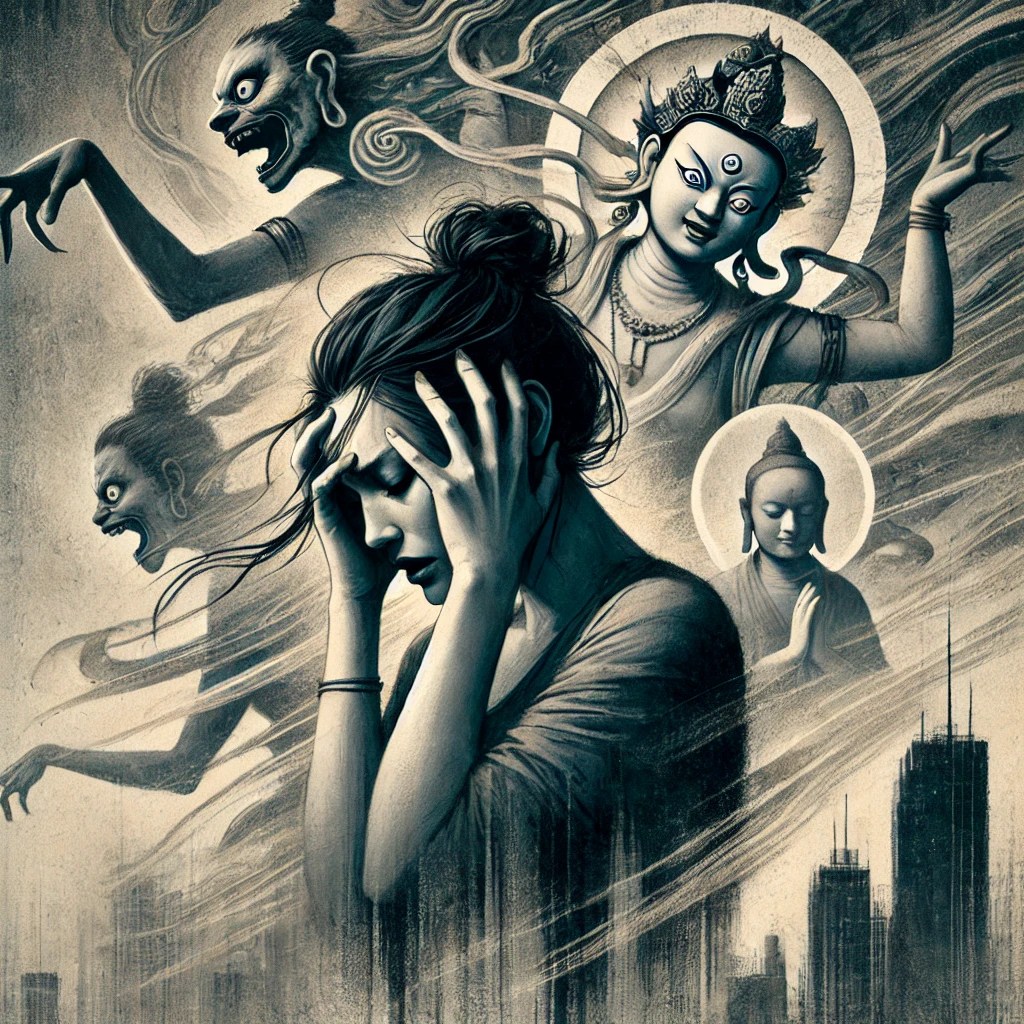

Years later, after surviving the catastrophic unraveling of my own tantric path due to the betrayal by male Buddhist teachers, the exposure of their sexual abuses, and the psychic annihilation that followed, I began to study the origins of tantra in earnest. Through the research of Alexis Sanderson and others, I learned what my experience at Dakshineswar had already shown me: that the yoginī tantras of Tibetan Buddhism arose from the same crucible of medieval Hindu Śaiva and Śākta practice⁷. Vajrayoginī, the red goddess of my own initiations, was in essence a Buddhized form of Kali. The goddess in both traditions can give blessings and boons, but she can become, in an instant, a terrifying and destructive demon with her own set of intentions and cosmic laws.

That insight came at great cost. The deeper I studied, the more clearly I saw that tantra, in both Hindu and Buddhist forms, was inseparable from forces of domination, secrecy, and power. The same ecstatic current that once inspired devotion also lurked behind manipulation and abuse. In the West, these darker currents were long dismissed or hidden, until the many scandals of 2017 tore the veil away.

My visit to Kali’s temple remains a paradox. In that moment I felt only grace: the raw, overwhelming presence of the divine feminine. But in hindsight, I experienced Kali as both mother and destroyer, blessing and devourer. She welcomed me to Calcutta with open arms, but in time, in her Buddhist form as Vajrayogini, she stripped me of everything I held dear in order to completely destroy my body, mind, and soul. By the grace of the highest divinity, the eternal Christian God, I survived and am still alive to tell the tale.

Notes

- Dakshineswar Kali Temple, Wikipedia, last modified 2025.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.; see also Dakshineswar Kali Temple official site, Places in Dakshineshwar (dakshineswarkalitemple.org).

- Dakshineswar Kali Temple, Britannica.

- Ibid.; Ramakrishna’s association documented in Swami Nikhilananda, The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna (New York: Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center, 1942).

- Alexis Sanderson, “The Śaiva Age: The Rise and Dominance of Śaivism during the Early Medieval Period,” in Genesis and Development of Tantrism, ed. Shingo Einoo (Tokyo: Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo, 2009), 41–350.