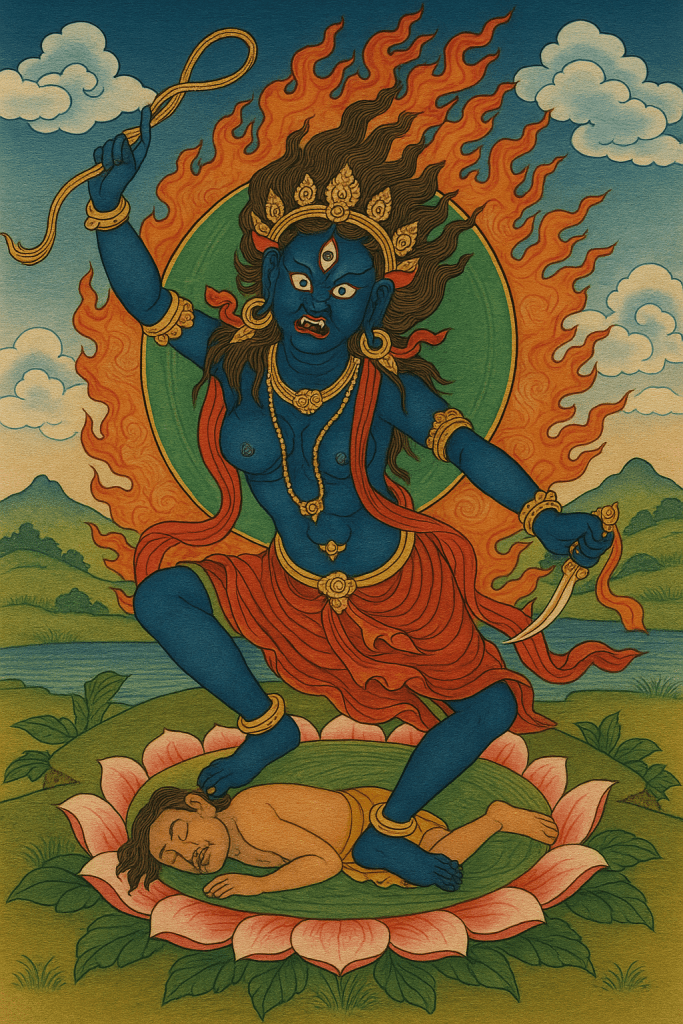

Kurukullā, the red goddess of magnetizing, depicted in a traditional Tibetan thangka style, embodying the tantric power to attract and bind.

Western seekers approaching Tibetan Buddhism are usually drawn to its most humane face. Chenrezig practice promises the cultivation of boundless compassion through visualizing Avalokiteśvara and reciting his mantra Om Mani Peme Hung. Tonglen “taking and sending” practice trains the mind to breathe in the suffering of others and breathe out relief. These sincere aspirations are the public face of Tibetan Buddhism. Yet this religion also preserves a hidden curriculum. Alongside compassionate practices sit the four activities that structure tantric ritual: pacifying, enriching, magnetizing, and subjugating. This fuller picture is rarely presented to beginners, and yet it has consequences for any claim to informed consent.[1]

The four activities: not just compassion

The four activities, known in Sanskrit as caturkarman, classify tantric rites by their intended effect:

- Pacifying (śāntika) calms illness and obstacles.

- Enriching (puṣṭika) augments longevity, merit, charisma, retinues, and wealth.

- Magnetizing (vaśīkaraṇa) draws people and circumstances into a chosen orbit.

- Subjugating (abhicāra) forces or destroys enemies.

These are not modern inventions but standard categories across tantric manuals and commentaries.[2]

While Western students are typically introduced to the activities of pacifying and enriching, the other two, magnetizing and subjugating, remain obscure, despite being prominent in tantric ritual literature. Historian Jacob Dalton has shown that violent tantric rites were not marginal but integral, even harnessed by Tibetan states to consolidate power in the medieval period.[3]

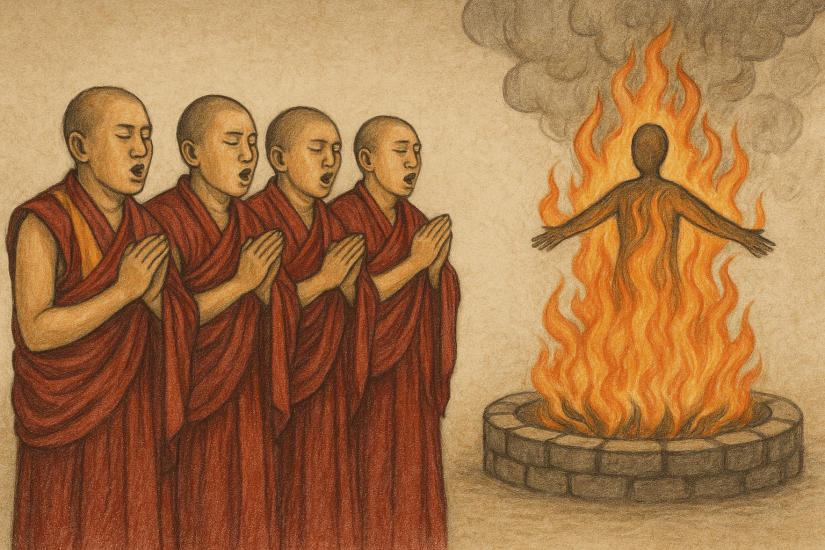

Kurukullā: the red goddess of attraction

Kurukullā, a red goddess associated with Amitābha and Tara, epitomizes magnetizing. In traditional texts she is praised as the deity of attraction, and in Tibetan sources she is sometimes known as the “Magnetizing Tara.” She is depicted holding a arrow, bow, flower and hook, all instruments of enchantment. [4]

Contemporary dharma centers sometimes describe her as a deity of love and influence, a kind of esoteric Cupid. But Tibetan ritual manuals, as catalogued by Stephan Beyer and translated in part by modern scholars, show that Kurukullā rites include binding the loyalty or desire of others.[5]

The omission of this material in introductory teachings is significant. Students often hear of compassion, not of enchantment and coercion.

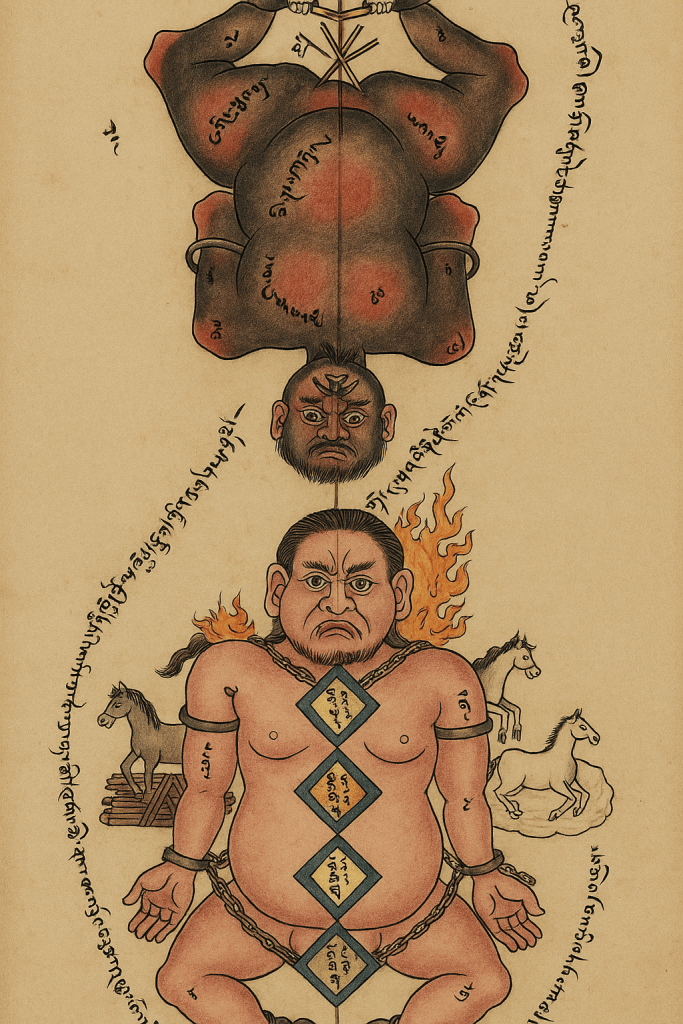

Subjugation and tantric violence

Subjugating rituals, by contrast, can be overtly violent. Dunhuang manuscripts detail effigy rites and “liberation” practices, in which enemies are ritually slain to protect practitioners and their patrons. Dalton notes that these methods scaled from local shamanic forms into state-sanctioned tantric technologies by the 13th century.[6]

Even today, wrathful practices remain part of Tibetan public culture. Cham dances of Mahākāla, staged annually in monasteries, dramatically enact the destruction of obstacles. While these are often seen as symbolic, their presence keeps alive a framework where wrathful force is ritually mobilized against perceived threats.[7]

Samaya: the binding vow

In Highest Yoga Tantra empowerments, disciples take vows of refuge, bodhisattva vows, and tantric samaya commitments. Samaya is described as a “sacred bond” with the guru and the deity. Root downfalls include disrespecting the master or revealing tantric secrets. Breach is said to bring spiritual ruin.[8]

This means that students who take empowerments without understanding the full scope of tantric practices, including magnetizing, subjugating, and punishment rites, are effectively giving consent under partial information. Despite not understanding fully what they are entering into, the bond of samaya can become a blanket mechanism of control.

As the 17th Karmapa indicated in teachings earlier this year, samaya breakers are spoken of in language that implies wrathful retribution, both spiritual and physical. The retribution he described is not symbolic but actual. See my essay, “Read Between the Lines,” for more on this.[9]

Survivors’ voices

Accounts from survivors and critical practitioners suggest that magnetizing and wrathful practices are not just metaphors. Women have described experiences of sexual energy being manipulated at a distance, sometimes calling it a form of “astral rape.” Whether one interprets this as energetic manipulation or psychological intrusion, the perception of violation is real.

Lion’s Roar published testimonies arguing that samaya has been used as a principal mechanism of coercion in abuse cases. Independent investigations of groups like Shambhala document patterns where devotion and secrecy prevented victims from speaking out.[10]

Buddhist communities are now grappling with these realities. Some organizations are introducing explicit consent policies, recognizing that the charisma of a guru, altered states of consciousness induced during a ritual, and the binding reality of vows can impair a student’s capacity to freely choose.[11]

Historical context does not erase ethical duty

Scholars such as Ronald Davidson have contextualized tantric violence as a product of medieval frontier politics and kingship.[12] This explains how such rites developed. But historical context does not remove the ethical obligation to disclose them to modern students.

Without disclosure, the vows taken in empowerments are not truly informed. The student consents to Buddhist compassion, but is bound to a system that also contains sexual enchantment, psychological manipulation, and deadly punishments.

Conclusion

The compassionate practices of Chenrezig and Tonglen have a genuine power to transform, yet Tibetan Buddhism’s esoteric side contains hidden technologies that are not peaceful but harmful: the rites of magnetizing, subjugation, and punishment. These are attested in texts, preserved in ritual, and acknowledged by scholars and survivors alike. Until these dimensions are more fully disclosed, the vows taken in tantric empowerments remain shadowy. Consent given without knowledge of the whole spectrum of practice is not true consent. It is, as this essay argues, an illusion.

Source Notes

1. Rigpa Wiki, “Four activities,” accessed 2025.

Rigpa Wiki is a practitioner-maintained encyclopedia that summarizes key Vajrayana concepts. Its entry on the “four activities” clearly lays out pacifying, enriching, magnetizing, and subjugating as the classical categories of tantric ritual. It is not a critical academic source, but it reflects how contemporary Tibetan Buddhist institutions themselves present the material.

2. Study Buddhism, “What is Samaya?” and “Empowerment.”

Study Buddhism is a project led by Alexander Berzin and colleagues, offering accessible introductions to Buddhist theory and practice. These entries explain samaya as a binding relationship with a guru and empowerment as the ritual granting of authority to practice tantra. They are useful for showing how Tibetan teachers explain vows and empowerments to Western audiences.

3. Jacob P. Dalton, The Taming of the Demons: Violence and Liberation in Tibetan Buddhism (Yale University Press, 2011).

Dalton’s book is a landmark study of ritual violence in Tibetan Buddhism. Drawing on Dunhuang manuscripts, he shows that wrathful rites, including violent subjugation and “liberation” rituals, were integral to tantric practice. Dalton’s work challenges romantic views of Buddhism as purely peaceful.

4. Wikipedia, “Kurukullā”

The Wikipedia entry gives a concise overview of Kurukullā as a magnetizing deity across Buddhist cultures.

Tomlin, Adele. “MAGNETISING RED QUEEN, KURUKULLĀ: ‘Outshining the perceptions of others and bringing afflictive emotions under control’ teaching of 8th Garchen Rinpoche,” Dakini Translations, 8 June 2021. Available at: https://dakinitranslations.com/2021/06/08/magnetising-dancing-queen-kurukulla-outshining-the-perceptions-of-others-and-bringing-afflictive-emotions-under-control-teaching-of-8th-garchen-rinpoche/

5. Stephan Beyer, The Cult of Tārā: Magic and Ritual in Tibet (University of California Press, 1973).

Beyer’s study remains a foundational ethnography of tantric ritual in Tibet. His translations of ritual manuals include examples of both compassionate and wrathful practices, including rites of attraction and subjugation. It is particularly valuable for showing how deity practices were embedded in everyday Tibetan religious life.

6. Dalton, Taming of the Demons; see also Jacob P. Dalton, “A Crisis of Doxography,” in Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 28, no. 1 (2005).

In addition to his book, Dalton’s article “A Crisis of Doxography” analyzes how violent rites were classified in Tibetan scholastic traditions. He shows that even systematizing scholars struggled to reconcile wrathful tantric methods with Buddhist ideals, which underscores their presence and their tension.

7. Associated Press, “Wrathful deities in Tibetan Cham dance,” 2024.

This news report covers annual cham dances in Tibet and in exile communities, where wrathful deities like Mahākāla are invoked to repel obstacles. It illustrates that wrathful practices are still a living part of Tibetan Buddhist culture, even if framed from the public as symbolic or theatrical.

8. Study Buddhism, “Samaya”; Rigpa Wiki, “Empowerment.”

Both entries describe the vows and commitments made during empowerment rituals. They confirm that samaya includes strict obligations to the guru and to secrecy. Their language highlights how the bonding process is explained to new students, and how much is left unspoken.

9 “Read Between the Lines: A Glimpse Into the Dark Heart of Guru Devotion,” Tantric Deception, April 4, 2025.

This essay analyzes a teaching by the 17th Karmapa, where he discussed samaya and hinted at punitive consequences for breaking devotion. It shows how even contemporary high lamas continue to invoke the discourse of samaya enforcement, reinforcing the concerns about consent.

10. Lion’s Roar, “When Samaya is Used as a Weapon,” 2018; Buddhist Project Sunshine Reports, 2018–2019.

Lion’s Roar published reflections by teachers and survivors on how samaya language has been used to silence or coerce students in abuse cases. Buddhist Project Sunshine was a grassroots effort to document sexual misconduct in Shambhala and other Tibetan Buddhist organizations. These sources provide survivor-centered evidence of how samaya functions in practice.

11. Buddhist Ethics Working Group, “Consent in Vajrayana,” 2021.

This collective statement from Buddhist practitioners and ethicists proposes new standards for sexual and spiritual consent in Vajrayana contexts. It emphasizes enthusiastic, ongoing consent and rejects the misuse of tantric language to excuse coercion. It is an attempt at reform efforts from within the tradition.

12. Ronald M. Davidson, Indian Esoteric Buddhism: A Social History of the Tantric Movement (Columbia University Press, 2002).

Davidson’s historical study situates tantric Buddhism in the political and social context of medieval India. He shows how esoteric practices were bound up with kingship, warfare, and elite patronage. His work helps explain how violent and manipulative rites could become integral to the tradition, even if they clash with Buddhist ethics.