A Hidden Side of Tantric Buddhism

Buddhism is usually presented in the West as a religion of mindfulness and compassion. But hidden in its tantric wing is something darker. In the eighteenth century, Sélung Shepa Dorjé (Sle lung Bzhad pa’i rdo rje) compiled a sixteen-volume cycle called Secret Gnosis Dakini (Gsang ba ye shes mkha’ ’gro, or GYCK). This was not just a collection of esoteric philosophy, but also a grimoire filled with magical spells.

According to Cameron Bailey in The Magic of Secret Gnosis: A Theoretical Analysis of a Tibetan Buddhist “Grimoire,” grimoires of spell instructions are common in Tibetan Buddhism. They often appear inside larger tantric cycles like the GYCK or in the collected works of great lamas. As the scholar Berounsky, cited by Bailey, put it, the operations in such texts are “an amalgam of tantric interventions combined with popular magic.” [1]

Volumes four and twelve of the GYCK preserve dozens of rituals for worldly power. The twelfth volume in particular reads like a magician’s handbook. It does not hide its intent; it offers ninety-two spells to heal, protect, enrich, and subjugate.

Rituals of Control

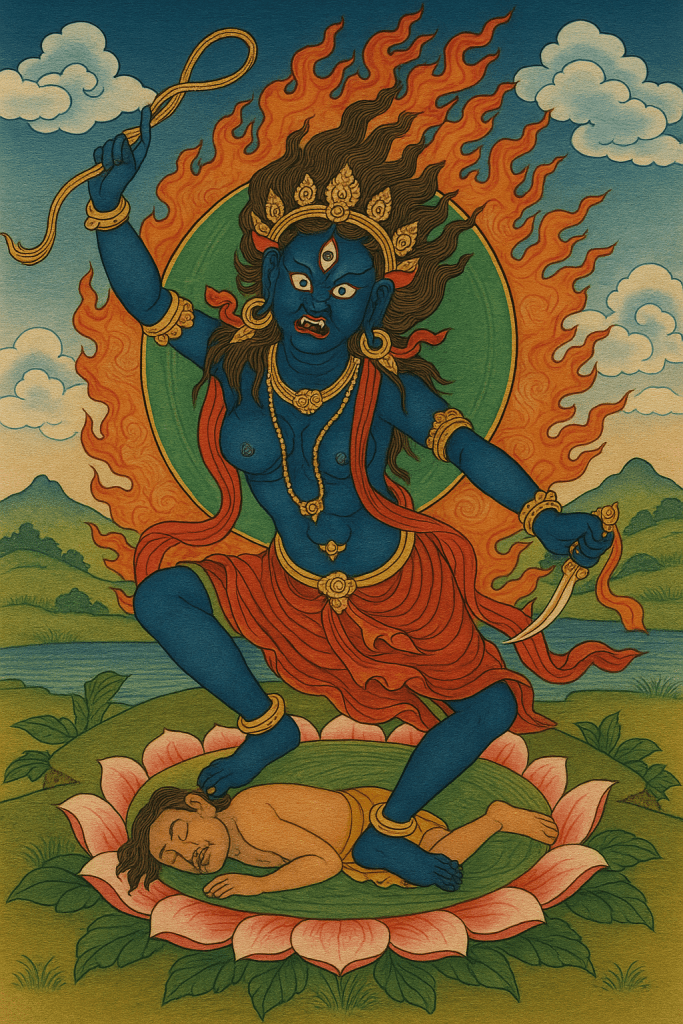

Among these spells are some dedicated to domination. Far from the common image of Buddhism as a purely gentle path of liberation, the Secret Gnosis spells allowed practitioners to bind and control others. One entire text, The Magic Lasso, instructs adepts on capturing their targets through visualization and mantra. Other spells direct them to create talismans and effigies, ritually charged to influence or destroy enemies.

Bailey emphasizes that these rituals work by merging tantric deity yoga with ritual techniques: the practitioner visualizes themselves as a wrathful god, projects light rays at the target, and seals the action with mantra. Your meditation becomes, in effect, a weapon.

The Spellbook as Technology

The grimoire aspect of the Secret Gnosis cycle cannot be overlooked. It contains practical instructions for bending reality to one’s desire. Substances like herbs, turquoise, and even urine or flesh are prescribed as tools of ritual practice.

Bailey notes that these spells are framed within a bodhisattva ethic. They are said to protect the Dharma or defend communities. Yet to modern eyes, they read unmistakably as instructions for control. This is where interpretation diverges. Bailey highlights the philosophical and ritual integration, while a critical lens reveals the coercive logic beneath the compassionate rhetoric.

A Tradition of Ambivalence

Figures like Milarepa warned against sorcery, even though his story is entangled with it. The Buddhist tradition as a whole often drew a line between miracle powers that “arise naturally” from meditation and deliberate ritual magic. But that line was blurred from the beginning. The Secret Gnosis makes clear how deeply magical domination was preserved within the canon.

Conclusion

The Secret Gnosis Dakini cycle exposes a side of tantric Buddhism rarely acknowledged publicly. Bailey shows that its grimoire-like sections are integral to tantric practice, not just marginal curiosities. What I emphasize here is that these spells—especially those of subjugation—show a system where manipulation was not an aberration but an option built into the tradition. What is presented today as a path of compassion was also, sometimes, a path of great harm.

[1] Cameron Bailey, “The Magic of Secret Gnosis: A Theoretical Analysis of a Tibetan Buddhist ‘Grimoire,’” Journal of the Korean Association for Buddhist Studies 93 (2020): 535–570.

Sounds very similiar to works like Picatrix or the investigations of Marsilio Ficino (or even Giordano Bruno) in the West: there is at least an acknowledgement of the sovreignty of God and admonitions to virtue, yet some of the contents are unnervingly diabolical, especially in the former. Interesting to see a similar trajectory in the East. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent point! I’ll check them out. I wasn’t familiar with them.

LikeLike

Tread warily! Ficino was a himself priest, but there were (and perhaps in some sense still are) strains of “magic” that was promulgated even among the clergy. As the Desert Fathers might advise, vigilance is key. May Almighty God bless and keep you safe.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your comment and your warning. My understanding is that even if some individual priests experimented with esoteric practices, these things were never part of Catholic teaching and, in fact, were often condemned by the Church. In any case, scripture itself is very clear, both in the Old and New Testaments, that magic, divination, and sorcery are forbidden.

By contrast, the magical practices of Tibetan Buddhist tantra are not peripheral but central to that tradition. Its rituals depart not only from Christianity but also from the early teachings of the historical Buddha. The Buddha emphasized renunciation, compassion, and liberation through wisdom and meditation, and explicitly rejected charms, spells, and sorcery (Dīgha Nikāya 2, Sāmaññaphala Sutta). Tantric rites of subjugation and harm stand in direct opposition with these principles, showing how far tantra deviated from foundational Buddhism.

LikeLike