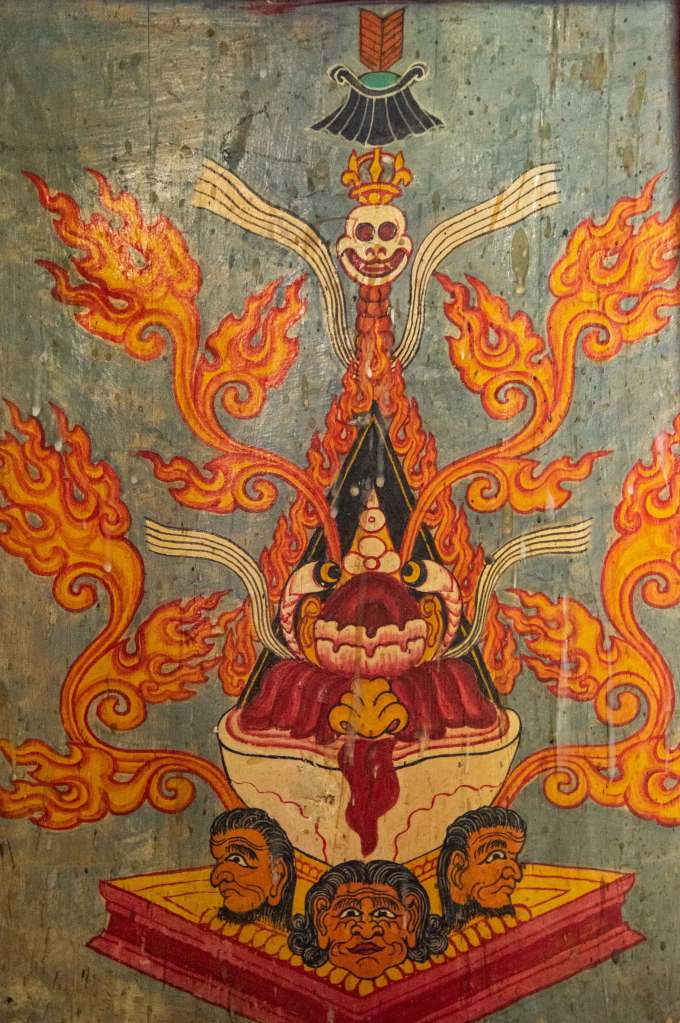

Photo by Rod Waddington (ShareAlike 2.0 Generic–CCBY-SA 2.0) https://flickr.com/photos/rod_waddington/

From the rugged mountains of Tibet, amidst stark terrains, came an occult tradition known as Tibetan Buddhism. For the first Westerners exposed to Tibetan Buddhism in the 1970s and ’80s, Tibet held a mystical allure as a sort of peaceful Shangri-la. But there lurks a darker history behind the pretty myths and the tranquil imagery of monks in maroon robes singing harmonious aspirations for the enlightenment of all sentient beings, one mired in tales of feudalism, power struggles, and bitter rivalries. Black magic rituals were, according to some legends, wielded as weapons, ensuring loyalty or punishing those who dared to oppose the spiritual leaders’ dictates.

The so-called “Lama Wars” were, in these tales, more than mere historical disputes over doctrines or territories. They were fierce battles where powers clashed, and the very air of Tibet cracked with tension as blood ran freely like the tributaries of a great river. As religious sects emerged, dividing the spiritual landscape, it wasn’t just philosophical differences that set them apart. History tells of clandestine conflicts between these sects, battles of magic and wit, with each side vying for dominance over the spiritual realm of Tibet.¹

Amidst this tumultuous backdrop, some say that the lamas had a special punishment reserved for the disciples who dared to question or challenge their actions. These unfortunate souls would find themselves cursed, with the weight of the entire tradition bearing down on them.

Historical Background

Tibetan Buddhism, also known as Vajrayana Buddhism or Lamaism, is a form of Buddhism that developed in Tibet and the Himalayan regions. It is a distinctive branch of Buddhism that incorporates elements from Indian Buddhism, Hindu tantra, and indigenous Tibetan religious traditions. Some earlier traditions of Buddhism criticize Vajrayana Buddhism as a distortion or perversion of the Buddha’s original teachings.

- Historical Development and Lineage: Buddha lived about 2,500 years ago, and Buddhism evolved and branched out over many centuries. Theravada, often seen as the school closest to the “original” teachings of the Buddha, primarily spread in South and Southeast Asia (i.e. Sri Lanka, Thailand, Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos). Tibetan Buddhism, on the other hand, developed much later and has incorporated many elements of the indigenous Bon religion of Tibet and especially the Indian tantric practices of Kashmir Shaivism. This amalgamation of practices and beliefs makes it distinct from the early forms of Buddhism, leading some Theravadins to see it as a deviation.

- Scriptural Basis: Theravada relies on the Pali Canon, particularly the Tripitaka, as its primary scriptural source. Tibetan Buddhism, while acknowledging these texts, places equal or greater emphasis on the Mahayana sutras and the esoteric Tantric texts. This difference in scriptural authority can lead to significant divergences in belief and practice.

- Doctrinal Differences: While core tenets of Buddhism like the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path are common to both traditions, their interpretations, and the importance placed on various practices can differ. For instance, Tibetan Buddhism’s rich pantheon of Bodhisattvas and deities, the emphasis on guru devotion, and the use of esoteric practices in the Vajrayana tradition might be seen as non-Buddhist or even heretical from a strict Theravadin standpoint.

- Cultural Elements: The cultural integration of Tibetan Buddhism with indigenous Tibetan elements makes it distinct and sometimes hard for Theravadin followers to recognize it as part of the same tradition. The rituals, art, meditation practices, and liturgy are significantly different.

- Views on Monasticism: Theravada Buddhism emphasizes the monastic life and the community of monks (the Sangha) as the primary path to enlightenment. Tibetan Buddhism, while valuing monasticism, also has a rich tradition of lay practitioners and yogis who achieve advanced spiritual states.

- Political and Historical Tensions: Over the centuries, political, and historical tensions between various Buddhist schools and nations might have also played a role in the differences in perceptions.

Tibetan Buddhism is characterized by its rich symbolism, complex rituals, and emphasis on meditation practices.

Key aspects of Tibetan Buddhism include:

- Lineage: Tibetan Buddhism places great importance on the transmission of teachings from teacher to student in an unbroken lineage. This lineage is believed to ensure the authenticity and purity of the teachings.

- Tantric Practices: Tibetan Buddhism incorporates tantric practices, also known as Vajrayana, which involve advanced meditation techniques, visualization, and rituals aimed at transforming ordinary experiences into spiritual paths. These practices are considered to accelerate the path to enlightenment.

- Deities and Mandalas: Tibetan Buddhism incorporates a pantheon of deities and celestial beings, which are often depicted in intricate mandalas. These deities are seen as embodiments of enlightened qualities and are invoked in rituals and meditation practices.

- Monastic Tradition: Monasticism plays a significant role in Tibetan Buddhism. Monks and nuns live in monastic communities and dedicate their lives to the study, practice, and preservation of Buddhist teachings.

- Reincarnation: Tibetan Buddhism holds the belief in reincarnation, which means that individuals are reborn after death. The recognition of reincarnated masters, such as the Dalai Lama and other high lamas, is an important aspect of Tibetan Buddhism.

Tibetan Buddhism has had a profound influence on Tibetan culture, art, and society. It has also spread to other regions, such as Bhutan, Nepal, Mongolia, and parts of India and China, where it has merged with local religious traditions. Today, Tibetan Buddhism continues to be practiced by millions of people worldwide, both within Tibetan communities and more recently among Western followers.

¹ In the mid-17th century, the Ganden Phodrang government established by the Fifth Dalai Lama, supported by the Mongol forces of Güshi Khan, acted forcefully against its principal rivals. The Karma Kagyu school’s garchen (encampment system) was nearly annihilated during these campaigns, with historical accounts describing the killing of large numbers of its monks and troops. The Jonang tradition was likewise suppressed: its chief monastery, Takten Phuntsok Ling, was seized and converted to a Gelug institution; its printing houses were closed; and its zhentong philosophical literature was banned from publication in Central Tibet. The lineage survived mainly through communities that persisted in Amdo and other eastern regions.

Sources:

- Cécile Ducher, The Collections of the Gnas bcu lha khang in ’Bras spungs Monastery, Revue d’Études Tibétaines 55 (2019).

- Jonang Foundation, “Frequently Asked Questions,” jonangfoundation.org.

- Himalayan Art Resources, “Tradition: Jonang Short History.”

- Tsadra Foundation, Buddha-Nature Project, “Jonang.”

- “Ganden Phodrang,” standard historical summaries.