Sam van Schaik’s Buddhist Magic: Divination, Healing, and Enchantment through the Ages (2020) attends to the often-overlooked domain of spells, incantations, divination, healing rituals, and what one might call “magic” in Buddhist traditions. The book offers, among other things, a translation of a Tibetan spell-book from the Dunhuang corpus and situates it in a broad historical trajectory of Buddhist ritual technologies. Yet in his 2021 review for H-Net, Cameron Bailey argues that the book suffers from significant omissions, conceptual limitations, and a subtle apologetic tone toward the more aggressive, violent, and transgressive forms of magic found in tantric Buddhism.¹ Bailey suggests that this tone is not simply stylistic but stems from deeper disciplinary biases about what “real” Buddhism is and what kinds of ritual power are acceptable to the scholarly gaze.

For readers of Tantric Deception, which is concerned with hidden ritual power, subversive techniques, and coercive practices in the “shadow” side of tantra, Bailey’s critique is especially pertinent. The benign, therapeutic, protective aspects of magic are only half the story; the aggressive, destructive, boundary-breaking elements are equally constitutive. Here the critique unfolds on three levels: (1) Bailey’s reading of Chapter 3 of van Schaik’s book (on the Ba ri be’u ’bum); (2) his broader objections to how van Schaik defines “magic” and frames the field; and (3) implications for the study of tantric magic and deception.

Bailey’s Critique of Chapter 3: “A Tibetan Book of Spells”

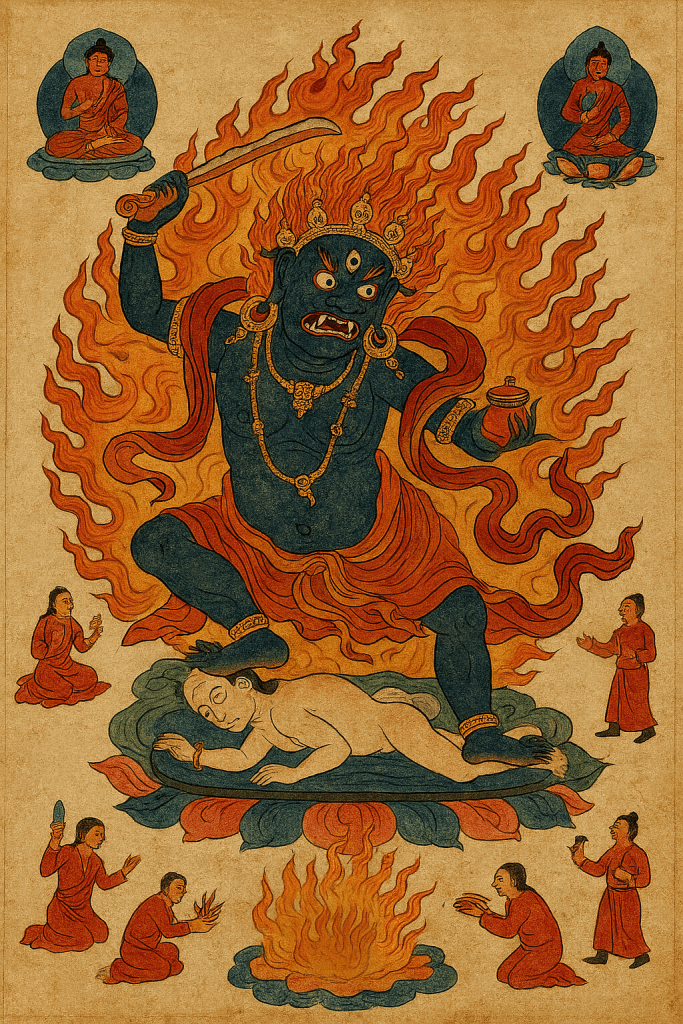

Bailey looks at Chapter 3, which discusses the Tibetan spell-book known as the Ba ri be’u ’bum, compiled by Ba ri Lotsāwa in the eleventh century.² Van Schaik concludes the chapter by pointing to the presence of violent magical ritual, what might be called “black magic,” in Buddhist spell-books and tantric scriptures such as the Vajrabhairava Tantra.³

Bailey’s critique is threefold:

- Understatement of prevalence. Van Schaik, he argues, seriously understates how widespread aggressive or destructive ritual practices are in tantric sources: “He could also have discussed the army-repelling magic in the Hevajra Tantra, the legendary violent magical exploits of the great tantric sorcerer Rwa Lotsāwa, or Nyingma Mahayoga scriptures, which are often positively brimming with black magic.”⁴

- Authorial discomfort. Bailey detects an obvious unease with “aggressive” magic and with rituals that use human remains as ingredients, suggesting van Schaik takes an apologetic tone when discussing them.⁵

- Scholarly bias. He links this tone to the longstanding tendency of Buddhist studies to privilege an idealized, pacifist Buddhism: “This kind of squeamishness … unconsciously replicates the biases of past generations of Buddhist scholars …. It is ultimately an artifact of Western observers thinking they know more about what should constitute normative Buddhism than their sources do …”⁶

For Bailey, this is not simply an omission but a rhetorical framing that soft-pedals the destructive dimensions of tantric magic.

Defining “Magic”: Bailey’s Broader Critique

Bailey extends his criticism to van Schaik’s opening chapters, where the author defines his working category of “Buddhist magic.” Van Schaik adopts a “family-resemblance” approach, noting that no direct equivalent of the Western word magic exists in Sanskrit or Tibetan.⁷ He describes magical practices as “focused on worldly ends, including healing, protection, divination, manipulation of emotions, and sometimes killing. The effects of these techniques are either immediate or come into effect in a defined, short-term period. The techniques themselves are usually brief, with clear instructions that do not need much interpretation, and are gathered together in books of spells.”⁸

Bailey objects that this framing:

- Over-narrows the field by confining magic to short-term, worldly ends, thereby excluding tantric practices that are long, soteriological, and embedded in complex ritual technologies.⁹

- Privileges text and literacy, focusing on manuals and specialists while sidelining oral, embodied, and popular forms of practice.¹⁰

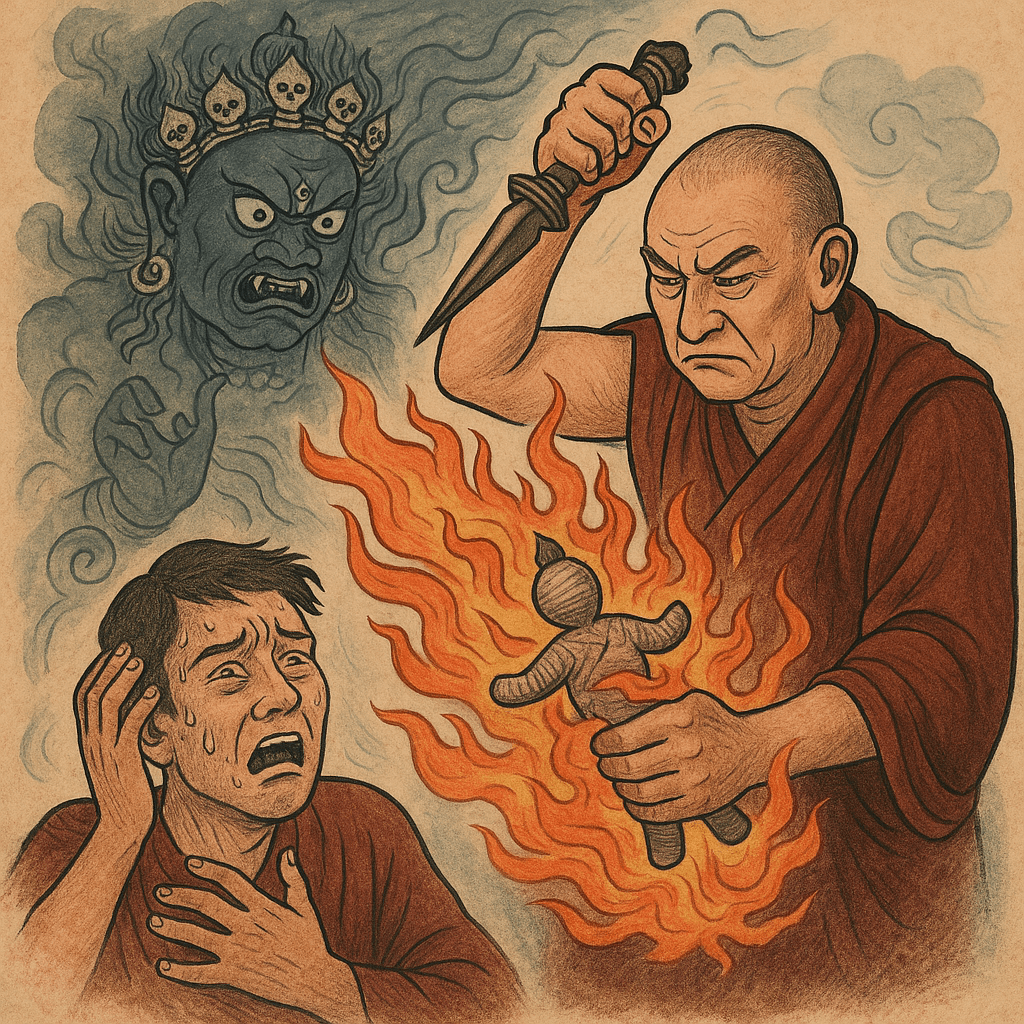

- Sanitizes the topic by foregrounding healing and protection while downplaying cursing, corpse-magic, and enemy destruction.¹¹

He concludes: “The way he defines and explains ‘magic,’ and describes how magical practices have traditionally been used by Buddhists across Asia, ends up inadvertently reinforcing many of the historical scholarly prejudices against magic that he ostensibly is trying to correct.”¹²

Van Schaik’s framework thus risks reproducing the very boundaries it seeks to challenge.

A Wider Blind Spot: Aggressive Magic and the Tantric World

Bailey argues that van Schaik should have engaged more fully with texts such as the Hevajra Tantra (with its army-repelling spells), the violent exploits of Rwa Lotsāwa, and the Nyingma Mahayoga scriptures filled with wrathful deities, corpse-magic, and enemy-destruction rites.¹³ By not doing so, or by treating such material as peripheral, van Schaik, he claims, sanitizes Tibetan Buddhism. “Van Schaik displays an obvious discomfort with the presence of ‘aggressive’ magic … and takes an apologetic tone when discussing them.”¹⁴

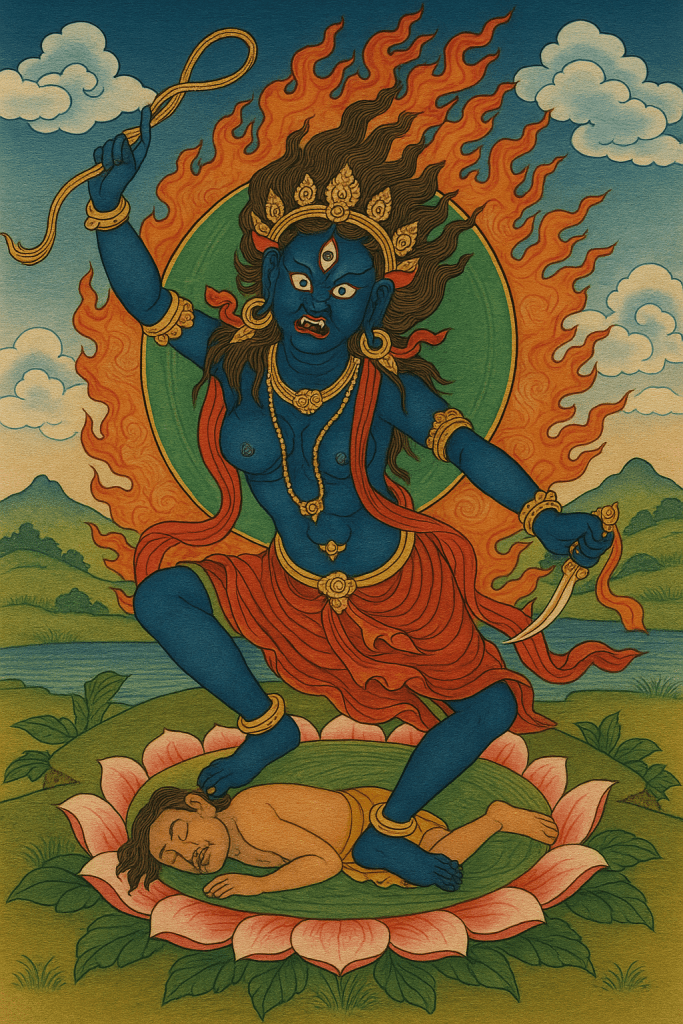

For scholars of tantra, this omission matters because tantric systems operate through extremes such as creation and annihilation, compassion and wrath, life-force and death. To highlight only healing and protection produces a partial picture of ritual power, one aligned with modern therapeutic Buddhism but detached from the coercive, political, and martial realities of historical tantric practice.

Bailey notes that while van Schaik does acknowledge violent spells (for example, in the Dunhuang materials), he does not trace how these recur and become canonical in later tantric systems.¹⁵ The result is a book that opens the field but keeps its most provocative elements at the margins.

Implications for the Study of Tantric Magic and Deception

Bailey’s critique has clear implications for the study of tantric ritual power:

- Broaden the definition of magic. Magic in Buddhist contexts is not confined to short spells. It includes deity-yoga, state-sponsored rituals, corpse-assemblage, body technologies, and institutions of ritual power.

- Recognize multiple aims. Magic serves soteriological as well as worldly purposes such awakening, subjugation, and mediation between spirits and humans.

- Acknowledge popular practice. Lay and non-monastic forms of magic interpenetrate elite traditions. Focusing solely on literate specialists truncates the field.¹⁶

Examining the Aggressive and Transgressive

To understand tantric magic fully, scholarship must confront its aggressive, destructive, and taboo aspects such as spells to kill or incapacitate, invocations of wrathful deities, rituals using human remains, and forms of mystical violence justified through tantric cosmology. When these are treated as aberrations, the study of tantric sovereignty, ethics, and power becomes impoverished.

Deception, Hidden Power, and Normativity

Bailey’s review also raises a methodological issue: the scholar’s discomfort can itself become a form of concealment. Reluctance to confront violent or transgressive material filters what is studied and what remains hidden. Bailey argues that van Schaik’s apologetic tone mirrors earlier generations of scholarship that preferred a morally “respectable” Buddhism.¹⁷

For research into deception, secrecy, and power in tantra, this is crucial. Reflexivity is required: how much of what we present as Buddhism is sanitized by our own unease with its violent, ambiguous realities?

Conclusion

Cameron Bailey’s critique of Buddhist Magic is more than a review. It is a reminder that scholarly framing shapes what becomes visible and what remains unseen in the study of ritual power. Van Schaik’s work makes an important contribution by bringing spells and enchantments to the center of Buddhist studies. Yet, as Bailey insists, by downplaying the aggressive and coercive sides of tantric magic, it perpetuates a pacified image of [Tibetan] Buddhism.

For those exploring tantra, deception, and hidden power, the shadow side of magic demands attention. Spells of domination and annihilation, corpse-magic, and state-sorcery are part of the story. Scholarly discomfort cannot determine what counts as legitimate tantric Buddhism. True understanding must include the violent and transgressive alongside the healing and protective.

Van Schaik opened the door; Bailey challenges us to step through. In tantra, concealment is not accidental, it is a method and a weapon. So too must scholarship have the courage to unmask it.

Notes

- Cameron Bailey, “Review of Sam van Schaik, Buddhist Magic: Divination, Healing, and Enchantment through the Ages,” H-Buddhism (H-Net Reviews), July 2021. https://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=56639.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 3.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 4.

- Van Schaik, Buddhist Magic: Divination, Healing, and Enchantment through the Ages (Boulder: Shambhala Publications, 2020), pp. 6–8; Bailey, review.

- Quoted in “Think Again Before You Dismiss Magic,” Lions Roar, April 2020.

- Bailey, review, p. 3.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 2.

- Ibid., p. 3.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 4.

References

Bailey, Cameron. “Review of Sam van Schaik, Buddhist Magic: Divination, Healing, and Enchantment through the Ages.” H-Buddhism (H-Net Reviews), 2021. https://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=56639.

Van Schaik, Sam. Buddhist Magic: Divination, Healing, and Enchantment through the Ages. Boulder: Shambhala Publications, 2020.

“Think Again Before You Dismiss Magic.” Lions Roar, April 2020.