In his essay Meanings of Violence in Tibetan Buddhism, Lin Kai develops themes first raised by Elliot Sperling: Tibetan Buddhism has never been simply the peaceful, pacifist tradition imagined in Western romantic projections. Both history and ritual demonstrate how violence was woven into Tibetan religious and political life¹, continuing into the present. As Kai underscores, and as Sperling noted before him, both Western interpreters and Tibetan voices have often gone to great lengths to overlook or obscure this troubling facet of Tibetan Buddhism.

Kai highlights how rulers, including the Fifth Dalai Lama, relied on military force to consolidate power and punish rebellion. As Sperling documented, the Dalai Lama issued explicit orders in the seventeenth century to annihilate enemies, words that expose a stark contrast to the modern image of Tibet².

The Fifth Dalai Lama’s commands were phrased in brutal, almost ritualistic terms:

Make the children and grandchildren like eggs smashed against rocks;

Make the servants and followers like heaps of grass consumed by fire;

In short, annihilate any traces of them, even their names.²

This edict was aimed at other Tibetan Buddhists, mind you. Amidst such warfare, Kai notes, not all monks accepted this with ease. Some were unsettled by the amount of time and resources demanded for war rituals, though few dared openly resist their lamas. A particularly striking passage from the Fifth Dalai Lama’s autobiography shows him wrestling with his own position as a Buddhist leader at war. He recounts the following dream:

“Looking through an open window on the eastern side of the protector-chapel, stood the treasurer [Sonam Rabten] and a crowd of well-dressed monks with disapproving looks. Shoving the ritual dagger into my belt, I went outside. Thinking that if any of those monks said anything, I would strike him with the dagger, I walked resolutely straight through them. They all lowered their eyes and just stood there. When I awoke, my illness and impurities had been completely removed; not even the slightest bit remained. I was absolutely overflowing with amazement and faithful devotion.” — Fifth Dalai Lama¹

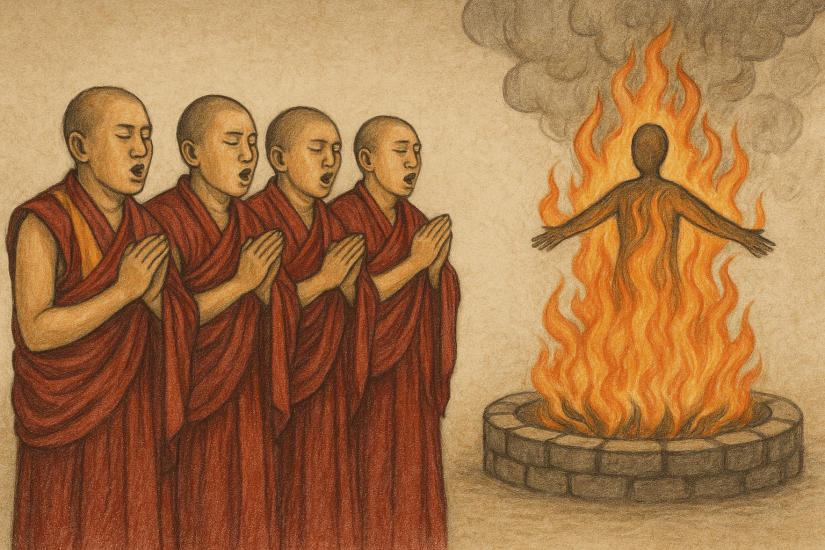

This moment captures the tension at the heart of Tibetan statecraft: the bodhisattva ideal of compassion colliding with the felt necessity of violence. Kai also emphasizes ritual violence, where wrathful deities and fierce imagery symbolize the annihilation of obstacles to enlightenment. These practices were not simply symbolic. They paralleled real political campaigns, where violent suppression against human beings was justified as protecting the Dharma¹.

Western audiences, however, have often distorted this history. Kai argues that Orientalist fantasies, especially those that cast Tibet as a timeless land of peace, obscure the record of blood and retribution¹. Sperling made the same point, noting how the Dalai Lama’s reputation as a Nobel Peace laureate stands in sharp tension with the historical evidence².

“Violence in Tibetan Buddhism cannot be neatly categorized as either barbaric or compassionate. It exists within a worldview where wrathful action and compassion may coincide, depending on context and intent.” —Lin Kai¹

In this worldview, compassion and violence were not opposites. Wrathful action could be seen as alright when it was thought to protect the Dharma or eliminate obstacles, even human ones. What emerges, then, is a very complicated and unsettling picture: violence was not an exception but an integral part of Tibetan Buddhist practice.

Kai’s work reinforces Sperling’s warning: if we want to understand Tibetan Buddhism as it is, rather than as we wish it to be, we must confront the ways in which violence was and still is sacralized within the tradition.

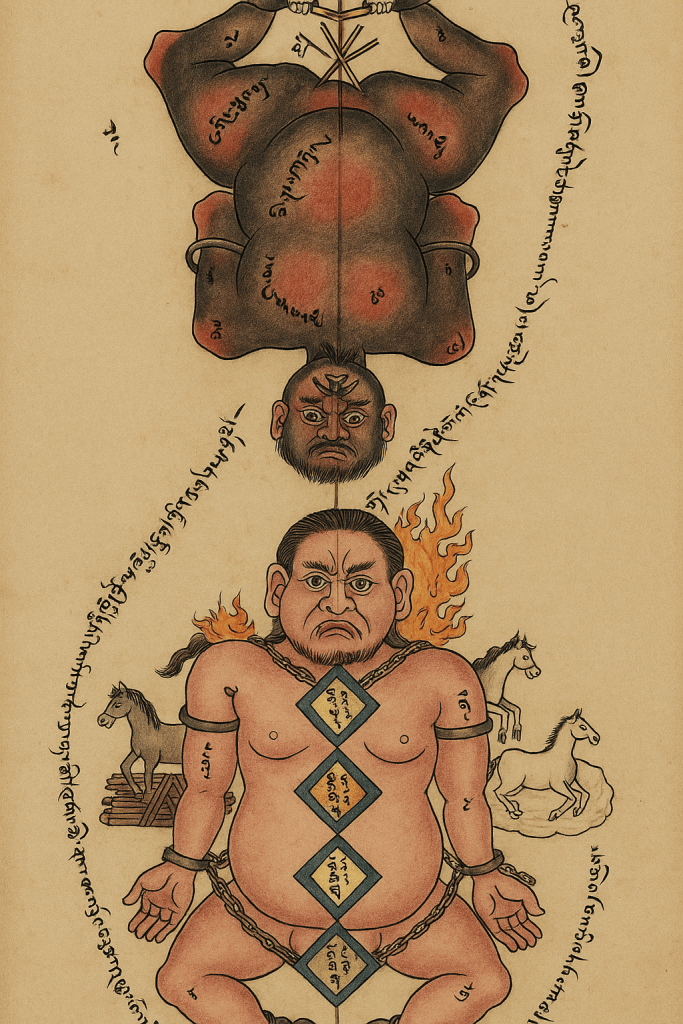

This type of linga resembles one depicted in the Secret Visions of the Fifth Dalai Lama, a visionary autobiography. It shows two figures to be ritually ‘liberated’ or killed, typical of effigies used in Tibetan Buddhist rites against so-called ‘enemies of the dharma.’ Such effigy sacrifices remain part of Tibetan Buddhist ritual practice today.

Footnotes

¹ Lin Kai, Meanings of Violence in Tibetan Buddhism, Substack, 2025.

² Elliot Sperling, Orientalism and Aspects of Violence in the Tibetan Tradition, Info-Buddhism, 2004.