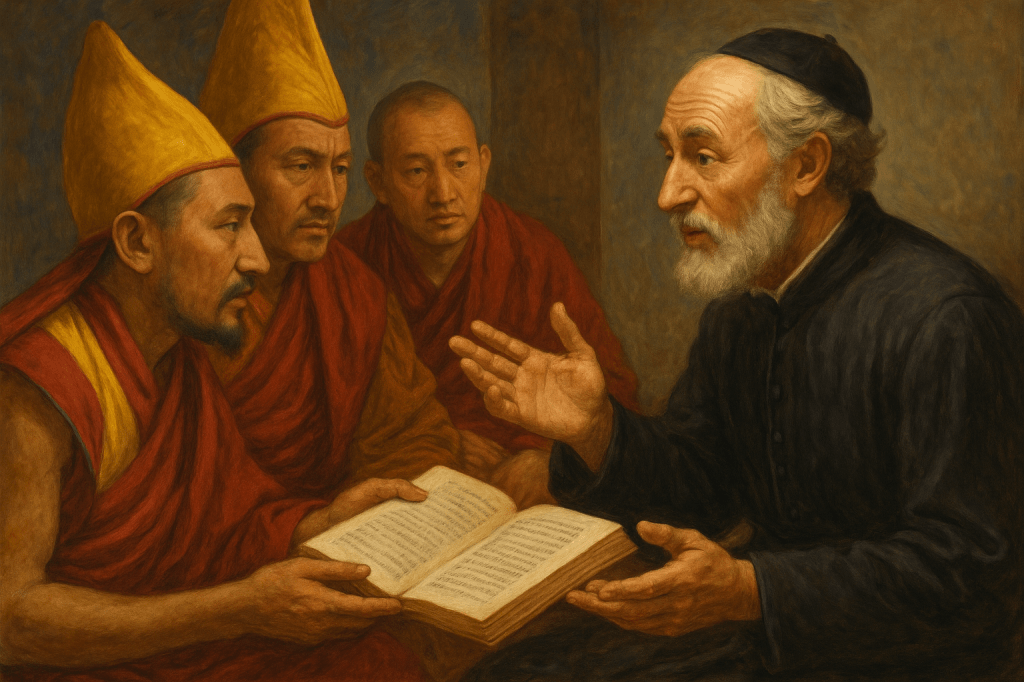

For centuries, Tibet has been a land that captures the imagination of the West: a high, remote world where spiritual and philosophical traditions intertwine with the stark beauty of the Himalayas. Among the earliest Westerners to truly engage with Tibetan thought was Ippolito Desideri, a Jesuit priest from Tuscany whose intellect, linguistic mastery, and deep curiosity made him one of the most remarkable missionaries of the early modern era. His work in the early 18th century stands as the first sustained encounter between Christianity and Tibetan Buddhism, marked not by confrontation but by a rare spirit of dialogue.

Early life and mission

Born in Pistoia in 1684, Desideri joined the Society of Jesus and quickly established himself as a scholar and teacher. His ambition was missionary work, and in 1712 he left Europe for India under the Jesuit Province of Goa. After years of difficult travel through Delhi, Kashmir, and Ladakh, he entered Lhasa on March 18, 1716. The Mongol ruler Lhasang Khan granted him permission to reside and study, marking the beginning of one of the most extraordinary intellectual encounters in religious history.¹

Tibet and the Capuchin dispute

Unknown to Desideri at the time, the Vatican’s Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith had already granted the Capuchin order exclusive rights over the Tibetan mission in 1703. This bureaucratic decision set the stage for a long jurisdictional dispute that would eventually cut short his work. In 1718, Propaganda Fide reaffirmed its assignment to the Capuchins and ordered the Jesuits to withdraw. After years of correspondence and litigation in Rome, a final decree in 1732 confirmed the Capuchins’ claim to Tibet.²

Immersion in Tibetan learning

In Lhasa, Desideri did what few missionaries before or since have attempted: he learned Tibetan thoroughly, studied Buddhist philosophy at Sera Monastery, and debated with monks in their own scholastic format. When the Dzungar invasion disrupted the capital in late 1717, he moved to Dakpo, where he continued to write and teach until his departure in 1721.³

Desideri’s approach was remarkable for its intellectual humility and rigor. He sought not to denounce Buddhism from ignorance but to understand it from within. By studying logic, metaphysics, and the Abhidharma, he entered into dialogue with the most sophisticated thinkers of his day in Tibet.

The Tibetan writings

Between 1718 and 1721 Desideri composed several original works in Tibetan. These writings, preserved in manuscripts now held in Rome and elsewhere, represent the earliest sustained Christian philosophical literature written in the Tibetan language.

- Tho rangs (“The Dawn”). An introductory dialogue presenting Christianity as the light that dispels ignorance and prepares the reader for deeper argumentation.⁴

- Lo snying po (“Essence of the Doctrine”). A concise catechism that sets out the essentials of Christian theology in the format of a Tibetan scholastic summary.⁵

- ’Byun k’uns (“Origin of Living Beings and of All Things”). A detailed critique of Buddhist cosmology and rebirth, arguing for a First Cause and a created order.⁶

- Nes legs (“The Supreme Good and Final End”). A philosophical exploration of the highest good, contrasting Christian teleology with Buddhist conceptions of nirvana.⁷

These works reveal a unique attempt to translate Thomistic metaphysics into the conceptual world of Tibetan Buddhism. Desideri employed debate forms familiar to the Geluk school and structured his reasoning through syllogisms recognizable to monastic scholars.⁸

His arguments against rebirth and emptiness

Desideri’s philosophical engagement centered on two main critiques of Buddhist doctrine: the cycle of rebirth and the concept of emptiness.

He argued that the karmic theory of rebirth fails to explain the origin of the first sentient beings, since it presupposes an infinite regress of prior lives without an initial cause. The moral and causal order of the universe, he wrote, points instead to an intelligent Creator who is both the origin and sustainer of being.⁹

Regarding emptiness (śūnyatā), Desideri contended that the very notion of dependent origination implies the existence of something independent. If everything is contingent and conditioned, reason demands an unconditioned ground. For Desideri, that ground is God, the necessary and self-subsistent cause of all things.¹⁰ He thus turned Tibetan logic toward a Christian conclusion, using the same tools his interlocutors used to defend their own tradition.

Conflict with the Capuchins and departure

While Desideri’s intellectual project flourished, his position within the Catholic hierarchy collapsed. The Capuchins, already active in Lhasa, viewed the Jesuits as intruders and appealed to Rome. After Propaganda Fide confirmed their authority, Desideri was ordered to leave Tibet in 1721. He made his way through India and returned to Europe in 1728, where he spent years defending the Jesuits’ case before ultimately submitting to the Vatican’s ruling.¹¹

The great narrative: Notizie istoriche del Tibet

Back in Rome, Desideri composed Notizie istoriche del Tibet (“Historical Notices of Tibet”), an extraordinary blend of ethnography, travel narrative, and theological reflection. In it, he described Tibetan geography, society, and religion with unprecedented detail and sympathy. Modern readers can access this work in the English translation Mission to Tibet by Michael Sweet and Leonard Zwilling, as well as in Donald Lopez and Thupten Jinpa’s Dispelling the Darkness.¹²

Legacy

Desideri died in 1733, only a year after the final Vatican ruling. His Tibetan manuscripts remained largely unknown until rediscovered in the 19th century. Today, he is recognized not only as a pioneering missionary but as a scholar who took the intellectual and spiritual life of Tibet seriously. His work stands as an early model of interreligious understanding, where dialogue was pursued through reason, language, and genuine respect.

Modern scholars such as Trent Pomplun, Donald Lopez, Thupten Jinpa, and Guido Stucco have shown that Desideri’s project anticipated later comparative philosophy by centuries. His writings remain a testimony to a unique moment when a European Jesuit and Tibetan monks met across the boundaries of faith to ask the same ultimate questions about being, purpose, and salvation.¹³

Footnotes

- Wikipedia, “Ippolito Desideri.”

- Michael J. Sweet, “Desperately Seeking Capuchins,” Archivum Historicum Societatis Iesu.

- Donald S. Lopez Jr. and Thupten Jinpa, Dispelling the Darkness: A Jesuit’s Quest for the Soul of Tibet.

- Guido Stucco, When Thomas Aquinas Met Nāgārjuna (includes translation of The Dawn).

- Elaine M. Robson, “A Christian Catechism in Tibetan,” University of Bristol thesis.

- Guido Stucco, When Thomas Aquinas Met Nāgārjuna (translation of The Origin of Living Beings).

- Opere tibetane di Ippolito Desideri, S.J., vol. IV (Toscano, ed.).

- Trent Pomplun, Jesuit on the Roof of the World: Ippolito Desideri’s Encounter with Tibetan Buddhism.

- Guido Stucco, When Thomas Aquinas Met Nāgārjuna, commentary section.

- Lopez and Jinpa, Dispelling the Darkness, analysis of Desideri’s argument on emptiness.

- Sweet, “Desperately Seeking Capuchins.”

- Ippolito Desideri, Mission to Tibet: The Extraordinary Eighteenth-Century Account, trans. Sweet, ed. Zwilling.

- Pomplun, Jesuit on the Roof of the World.