I am amazed that the PR for Tibetan Buddhism in the West managed for so long to conceal the extent of black magic practiced by lamas in Tibet historically and even to the present day. This concealment, aided and abetted by the squeamishness and obliviousness of some scholars, has to stop. In the dharma centers I was involved in, anything dark in Tibetan lore was relegated to the Bön religion, and the implication was that once Buddhism took hold in Tibet, any kind of evil acts such as harming or killing sentient beings was completely off the table. The truth is that black magic is in the lexicon of the highest lamas in the lineage as well as ngakpas and others. I believe these techniques are used liberally and current scholarship is finally exposing it.

Solomon G. FitzHerbert’s study of the mid-seventeenth century makes the core point plainly. He argues that tantric ritual and the rhetoric of ritual violence were central to how the Ganden Phodrang state established and legitimated power, not a peripheral curiosity. He writes that Tibetan sources “more than compensate” for the lack of hard military data with abundant materials about the “legitimation and maintenance of authority” through ritual technologies and narratives.¹

Before the rise of the Fifth Dalai Lama, Tibet’s Tsang rulers were already forging political alliances through tantric warfare. FitzHerbert shows that the Tsang kings deliberately patronized lamas famed for their mastery of wrathful and repelling rites. The most favored were the hierarchs of the Karma Kagyu, the “black hat” Karmapa and the “red hat” Zhamarpa, along with the Jonang scholar Taranatha, who was also enjoined to perform repelling rituals on behalf of his patrons.² Their alliances were explicitly religious and martial: an “ecumenical alliance in the name of defending religion and Tibet from foreign armies.”³

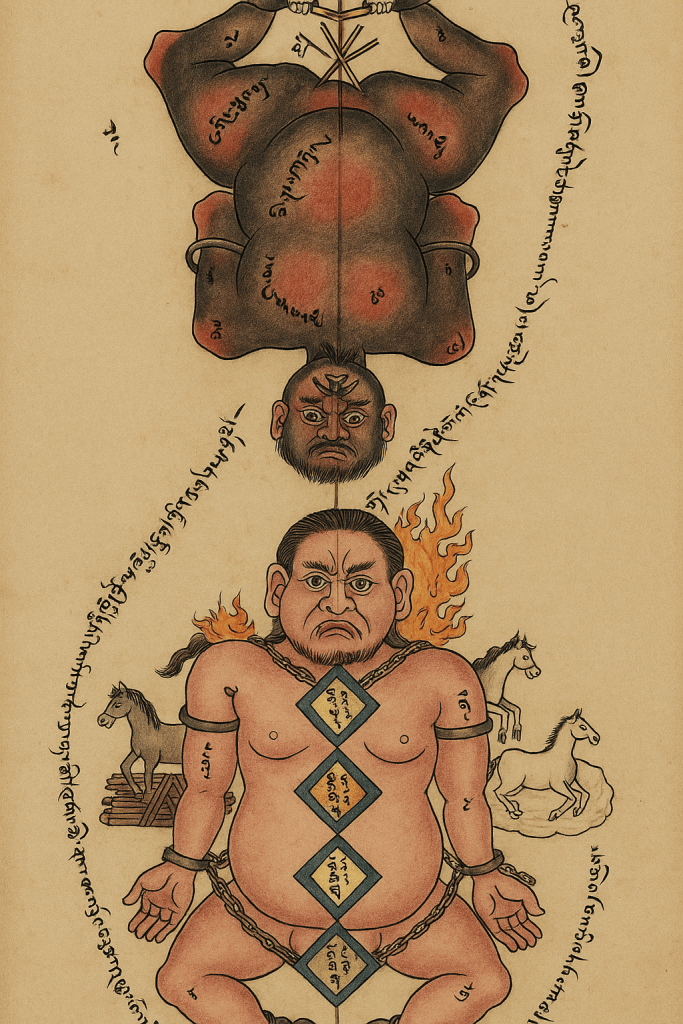

Among the Tsang rulers’ most celebrated ritual specialists was the Nyingma master Sokdokpa Lodrö Gyeltsen (1552–1624), self-styled “Repeller of Mongols.”⁴ A disciple of Zhikpo Lingpa, Sokdokpa was the main heir to the revealed cycle Twenty-Five Ways of Repelling Armies (Dmag zlog nyi shu rtsa lnga).⁵ His Mongol-repelling rites were widely famed, and he worked directly with the Tsang ruler Phuntsok Namgyel. One elaborate rite performed in 1605 to coincide with a Tsang military offensive involved producing “some 150,000 paper effigies of enemy soldiers.”⁶ These were ritually destroyed to annihilate the opposing force, with Bonpo specialists also enlisted for their expertise in magical harm.⁷

According to FitzHerbert, Phüntsok Namgyel successfully forged a broad anti-Geluk alliance using tantric technologies of protection and destruction.⁸ After his death, “reputedly at the hands of offensive magic being hurled at him by the Shabdrung Nawang Namgyal (Zhabsdrung Ngag dbang rnam rgyal) (1594–1651), founder of the state of Bhutan,”⁹ his son Karma Tenkyong (1604–1642) inherited a weakened position. The Shabdrung’s tantric assault, still treated in Bhutanese and Tibetan sources as a historical fact, thus became the legendary moment when a ruler famed for weaponizing ritual power was himself undone by it. It is one of the rare episodes where the logic of esoteric warfare entered the realm of accepted political history.

This is where the Fifth Dalai Lama comes into focus. FitzHerbert shows that in the 17th century the Great Fifth cultivated and systematized an official repertoire of destructive and protective rites in service of government aims. In his words, the Dalai Lama showed a “lifelong concern with learning, authoring and instituting an armory of defensive and offensive rituals for the mobilization of unseen forces” for the state.¹⁰ That program contributed to the Ganden Phodrang’s reputation for “magical power,” and helped stage what FitzHerbert calls the grandest “theatre state” in Tibetan Buddhist history.¹¹

FitzHerbert details three overlapping strategies. First, the new government suppressed, marginalized, or co-opted rival traditions of war magic associated with other schools, including Karma Kagyu and strands within Nyingma, while appropriating selective cycles that could be redeployed under Geluk authority.¹² Second, it rebuilt Nyingma institutions such as Dorjé Drak and Mindröling under Ganden Phodrang patronage, folding their esoteric prestige into the state project.¹³ Third, it sponsored new state rituals based on the Dalai Lama’s own visionary experiences, further centralizing ritual power in Lhasa.¹⁴

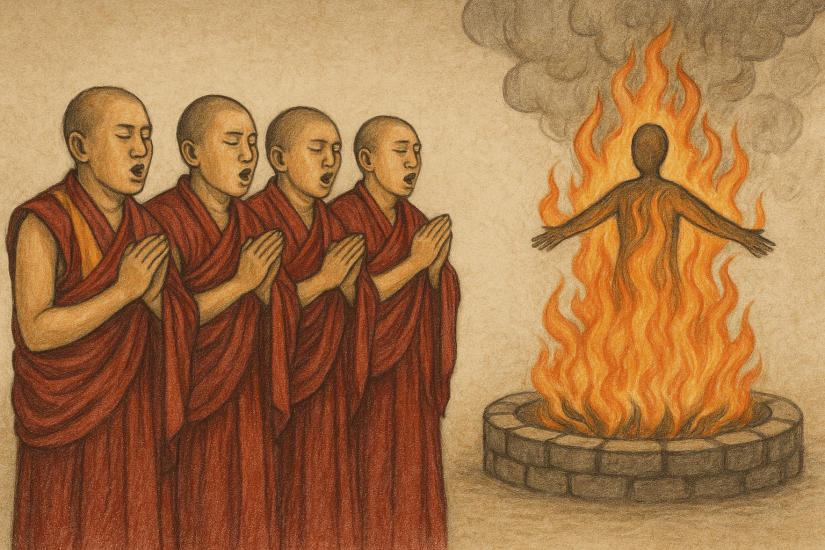

The rhetoric was not merely devotional. Lamas and ritual specialists acted as “bodyguards” whose professional task was destructive magic on behalf of patrons.¹⁵ Chroniclers attributed battlefield outcomes to the rites of powerful tantrikas. FitzHerbert highlights Chökyi Drakpa, famed for the Yamantaka cycle known as the “Ultra-Repelling Fiery Razor,” which centered on rites of “protecting, repelling and killing.”¹⁶ In one report, after deploying these rites against a Tümed encampment, “nothing was left behind but a name.”¹⁷

To grasp how such violence could be framed as meritorious, FitzHerbert shows the tantric logic that recasts killing as an enlightened “action” when performed by an empowered adept. The adept receives empowerment, performs extensive propitiation to forge identification with the deity, and then “incite[s]” and “dispatch[es]” oath-bound spirits to defend the dharma. By manipulating the five elements and the “public non-reality” of appearances, the practitioner can pacify, increase, control, or destroy, including against human enemies.¹⁸ The moral frame is clear in the sources he cites and translates. Killing is made licit because it is tantric, ritually purified and redirected as enlightened activity.¹⁹

FitzHerbert also situates Tibetan practices within a longer Indo-Buddhist lineage of war magic. He surveys Indian materials that speak of sainyastambha or army-repelling rites, and notes that the Hevajra states that “black magic for paralyzing armies,” is part of its “manifold purpose” and that the Kālacakra includes descriptions of war machines and siege methods such as “catapults, traps, siege towers, and so on,” alongside esoteric harm and protection.²⁰ He further notes the use of human effigies and effigy destruction in offensive rites against enemies, a hallmark of Tibetan ritual repertoires that drew on wider South Asian and even Indo-European precedents.²¹

Western idealization of Tibetan Buddhism has depended on ignoring this record. The lamas who administered and celebrated these rites were not outliers. They were the architects of a political order that fused charisma, ritual terror, and doctrinal justifications into a program of power. State-sponsored ritual violence was normalized in chronicles and hagiographies as enlightened means. The fact pattern is no longer obscure. It is all in the sources, and FitzHerbert has laid them out.

Although FitzHerbert’s focus is on state-sponsored ritual violence, similar technologies of harm have long been used by individual lamas against perceived enemies including, at times, their own disciples. The anthropologist Geoffrey Samuel has noted that the ritual power claimed by tantric masters can be turned inward, weaponizing spiritual authority to punish dissent or enforce obedience.²² In one well-documented episode from the nineteenth century, the treasure-revealer (tertön) Dorje Lingpa was said to have struck down a rival practitioner through wrathful ritual means, his death interpreted locally as a karmic consequence of opposing the lama’s command.²³ Such stories attest to a cultural logic in which ritual, psychic, or physical violence by enlightened masters could be valorized as the just expression of awakened power. I have personally been a victim of this deluded violent ritual power by Tibetan masters.

If Tibetan Buddhism is to be understood honestly outside Tibet, this history needs to be taught in dharma centers and discussed in scholarship without euphemism. The tradition’s own categories allow for destructive ritual and sanctified killing under certain conditions. Pretending otherwise does not protect the innocent devotees who arrive at dharma centers with open hearts seeking methods for developing compassion and loving kindness in service of enlightenment. Indeed, one must ask what kind of enlightenment tradition could allow, even glorify such violence.

Notes

- FitzHerbert, Rituals as War Propaganda, 91. FitzHerbert, Solomon G. “Rituals as War Propaganda in the Establishment of the Tibetan Ganden Phodrang State in the Mid-17th Century.” Cahiers d’Extrême-Asie 27 (2018): 49–119: https://www.persee.fr/doc/asie_0766-1177_2018_num_27_1_1508. (I first came across FitzHerbert’s article via a post on Adele Tomlin’s website http://www.dakinitranslations.com.)

- Ibid., 95–96.

- Ibid., 95.

- Ibid., 96.

- Ibid., 96.

- Ibid., 97.

- Ibid., 97.

- Ibid., 101.

- Ibid., 102–103.

- Ibid., 94.

- Ibid., 95.

- Ibid., 96.

- Ibid., 97.

- Ibid., 98.

- Ibid., 93.

- Ibid., 100.

- Ibid., 101.

- Ibid., 71.

- Ibid., 72.

- Ibid., 98–99.

- Ibid., 99.

- Geoffrey Samuel, Civilized Shamans: Buddhism in Tibetan Societies (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993), pp. 429–432.

- Cathy Cantwell and Robert Mayer, “Representations of wrathful deities in treasure literature,” in Tantric Revisionings: New Understandings of Tibetan Buddhism and Indian Religion (Leiden: Brill, 2008), pp. 131–133.