As a young practitioner, I was taught that the Buddhist tantras were revealed after the Buddha’s parinirvana (death). According to this myth, the Buddha appeared in a divine form to gods and advanced beings, delivering esoteric teachings that remained hidden during his lifetime. These secret instructions were entrusted to celestial beings, nāgas (serpentine spirits), and bodhisattvas, who later transmitted them when conditions were ripe. This framed the tantras as mystical extensions of the Buddha’s wisdom, distinct from his public teachings in the sutras.

However, modern scholarship, like Jacob Dalton’s work, suggests a different history. Instead of divine revelation, tantric rituals and methodologies likely evolved through independent ritual manuals rather than canonical scripture.

The Karma Kagyu Perspective

The Karma Kagyu tradition holds that tantras were revealed by Vajradhara, the Dharmakaya Buddha, through visionary transmission to highly realized beings like Tilopa. Some teachings were safeguarded by dakinis and nāgas, while others were hidden as terma (treasures) to be revealed later. These traditional narratives emphasize a mystical origin; however, Dalton’s research suggests that tantric Buddhism developed more organically, emerging from evolving ritual manuals.

If one takes the traditional Buddhist stance that tantra was revealed by the Buddha (or Vajradhara), then Dalton’s research presents a major challenge. It suggests that these teachings were likely developed and refined within Buddhist circles long after the Buddha’s time rather than being his direct transmission.

Sutras vs. Tantras

Sutras are foundational Buddhist texts attributed to the historical Buddha, emphasizing ethical conduct, meditation, and wisdom. These canonical scriptures are preserved in the Pali, Chinese, and Tibetan canons. In contrast, tantras focus on esoteric rituals, deity yoga, mantra recitation, and secret initiations aimed at accelerating enlightenment. Unlike sutras, tantras use symbolic, coded language and require initiation from a qualified teacher.

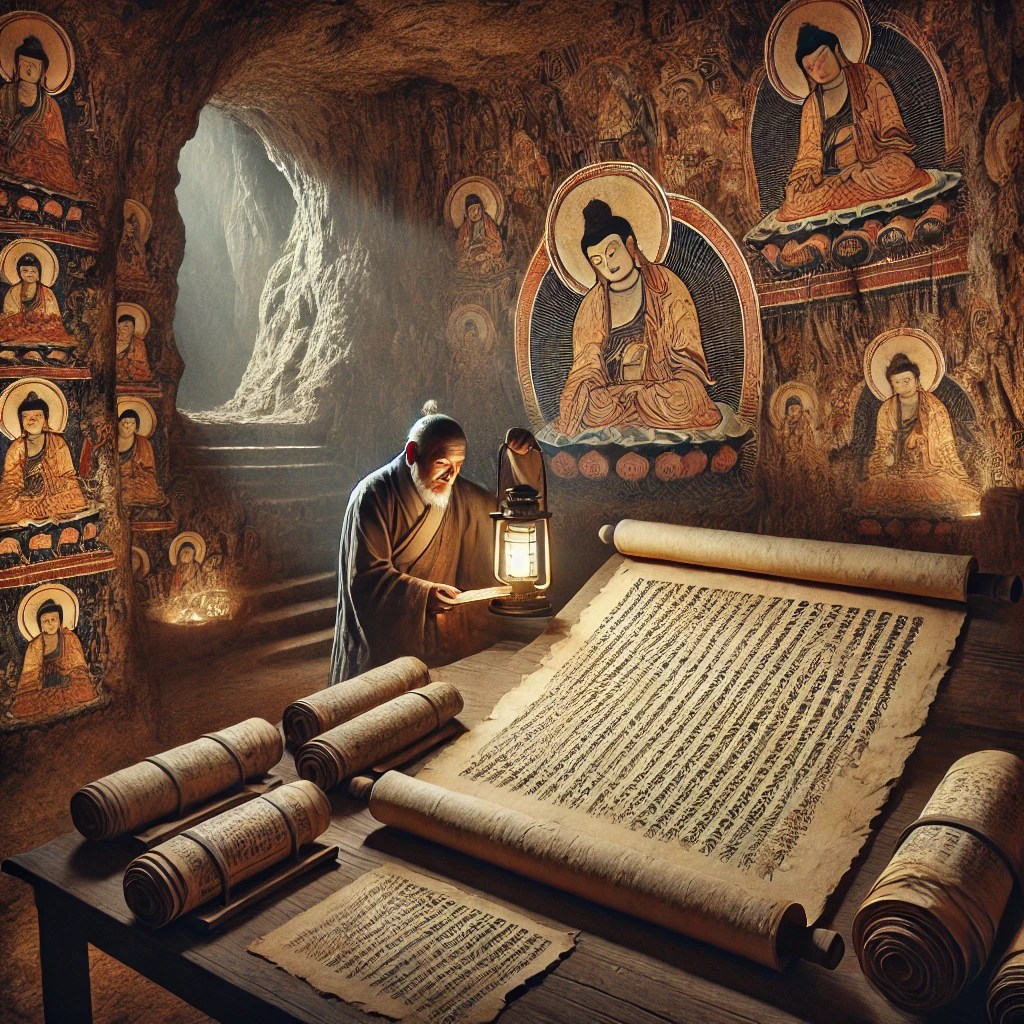

The Dunhuang Manuscripts and Ritual Manuals

The Dunhuang manuscripts, discovered along the Silk Road, offer insight into early tantric Buddhism. Dalton’s work with these texts suggests that tantric Buddhism initially developed through practical ritual manuals (Vidhis, Kalpas, and Sadhanas) rather than formalized scriptures. These guides were adapted and often discarded, making their historical traceability difficult.

Dalton found that these manuals were frequently appended to or inserted into Dharani sutras, but also existed independently.[1] This suggests that Buddhist rituals did not originate from sutras but were already in practice before being formally recorded in scripture.

The Evolution of Tantric Practices

By the fifth century, ritual manuals became prominent alongside Dharani sutras, marking a shift toward applied spirituality. The rise of altar diagrams, temple worship, and visualization techniques in Buddhist rituals coincided with Hindu esoteric traditions, reflecting a cross-pollination of practices.

Conjuring the Buddha: A Reversal of Scriptural Authority

Jacob Dalton’s book Conjuring the Buddha: Ritual Manuals in Early Tantric Buddhism, explores how tantric Buddhism is deeply ritualistic and magical, emphasizing that practitioners sought to conjure the Buddha rather than merely study doctrine.

A key argument in his work is that ritual practices predated and shaped canonical texts, rather than the traditional assumption that textual sources dictated practice. This challenges the linear evolutionary model that sees tantric Buddhism as a straightforward development from Mahayana sutras. Instead, Dalton suggests that lived ritual traditions influenced the formation of canonical texts, making tantric Buddhism a dynamic and experiential tradition rather than a purely doctrinal one.

Rethinking Tantric Buddhism’s Origins

Dalton’s research does not outright prove that tantra did not come from the Buddha, but it strongly challenges the traditional Buddhist claim that tantras were directly revealed by him (whether in his historical form or as Vajradhara). Instead, it suggests that tantric Buddhism developed as an evolving ritual tradition rather than being a fully formed teaching originating from the Buddha himself.

Here’s why:

- Ritual Practices Evolved Separately from Canonical Teachings

Dalton’s findings indicate that tantric practices were initially recorded in independent ritual manuals that were later appended to or integrated into Dharani sutras. This suggests that these practices were not originally part of the Buddha’s recorded teachings but emerged over time within Buddhist communities. - No Direct Scriptural Evidence from Early Buddhist Texts

The earliest Buddhist texts, the Pali Canon and Mahayana sutras, do not contain fully developed tantric doctrines. Tantra, as it appears in Vajrayana Buddhism, became prominent centuries later, and its early development seems to be more of a gradual accumulation of esoteric ritual practices rather than a singular revelation by the Buddha. - Cross-Pollination with Other Esoteric Traditions

Many tantric elements such as mantras, deity yoga, mandalas, and ritual visualization, resemble practices found in Indian Shaiva and Shakta traditions. This suggests that tantric Buddhism developed through cultural and religious exchange rather than being an entirely unique transmission from the Buddha. - A Shift in Scriptural Authority

The fact that tantric practices existed before being formally written into Buddhist scriptures implies that tantric Buddhism may have been practitioner-driven rather than stemming from a singular enlightened source (such as the Buddha). The codification of these rituals into texts might have been an attempt to legitimize or systematize existing practices rather than recording an original revelation.

What This Means for the Traditional View

If one takes the traditional Buddhist stance that tantra was revealed by the Buddha (or Vajradhara), then Dalton’s research presents a major challenge. It suggests that these teachings were likely developed and refined within Buddhist circles long after the Buddha’s time rather than being his direct transmission. Whether this undermines the legitimacy of tantra as a Buddhist tradition depends on one’s perspective: traditionalists may argue that the Buddha foresaw and seeded tantric teachings in hidden ways, while scholars would argue that tantra is a later development influenced by various religious and ritual traditions.

[1] In Tibetan Buddhism, a Dharani Sutra is a type of scripture or sacred text that contains dharanis—extended formulas or phrases composed of Sanskrit syllables believed to carry spiritual power. These are similar to mantras but often longer and more elaborate.

Jacob Dalton, “Conjuring the Buddha,” YouTube, October 5, 2023, https://youtu.be/UVxdmvYaOq4?si=ADR5WqZVvrX88Qo3.

The full transcript of the lecture cited in the article can be read here:

Speaker: Jacob Dalton, Ph.D. | Distinguished Professor in Tibetan Buddhism, UC Berkeley

Thank you, Sanjot, for inviting me. It’s a strange experience to speak to a home crowd.

I’ve given a couple of talks on this book before, and those were more formal, in-depth lectures on specific elements of the book. But since those are all available online, I decided to take a different approach today—something a bit more personal and informal. I want to talk about the process I went through in writing this book.

Since many of you, particularly those in my seminars, have probably heard me discuss these ideas countless times—ideas I’ve been working with for nearly 20 years—I hope this will be the last time you have to listen to me talk about them.

This book began taking shape after I finished my Ph.D. and moved to London to work at the British Library. I was hired by the International Dunhuang Project, which had received a three-year grant to digitize the Tibetan tantric manuscripts in the Stein Collection.

A brief word on the Dunhuang manuscripts: they were discovered over a century ago in a cave along the Silk Road, near the city of Dunhuang. They are a treasure trove for scholars of Chinese and Tibetan religious studies, containing some of the earliest materials we have in Tibetan.

As part of this project, I worked alongside Sam van Schaik to catalog the tantric manuscripts. It was an incredibly fortunate three years, as my interests aligned perfectly with the project’s goals, allowing me to read through the collection extensively.

As I began working through these manuscripts, I noticed that previous scholarship had largely relied on the existing catalog of Tibetan manuscripts in London. Rather than being constrained by that framework, I decided to read through the manuscripts one by one, which led to the discovery of many new treasures.

At the start, I was so excited by my findings that I rushed to publish a few articles. Looking back, I wish I could retract them—they were filled with errors. I simply wasn’t yet qualified to fully understand the collection. Realizing this, I paused my publishing efforts to re-educate myself on the early history of tantric Buddhism in India, which ultimately delayed the completion of this book for nearly two decades.

The book does several things at once. It uses the Tibetan tantric manuscripts from Dunhuang as a window into the development of tantric Buddhism in India. My previous book, Taming of the Demons, used the same manuscripts to explore early Tibetan history, but this time I wanted to contextualize them in relation to Indian developments. While I am not a Sanskritist, I undertook the challenge of examining this material from an Indian perspective.

Despite what Sanjot may have said, much of the book is quite technical, dealing with the evolution of tantric ritual and how it functioned as a system. However, two larger arguments underpin the book.

First, I emphasize the importance of ritual manuals. The book is, in many ways, a study of early tantric ritual manuals as a distinct genre, particularly those preserved in Dunhuang.

Second, influenced by my time at UC Berkeley and conversations with colleagues like Paula and Allan, I began approaching these texts through a more literary lens.

The Discovery of Ritual Manuals as a Distinct Genre

In 2004, while working on an exhibition at the British Library, I was asked to write catalog entries for several manuscripts, including a Chinese diagram of an altar for the worship of Uṣṇīṣa Vijaya. Not knowing Chinese, I sought help in translating it, and I soon realized that nothing in the Uṣṇīṣa Vijaya Dhāraṇī Sūtra itself corresponded to the ritual practices depicted in the manuscript.

This led me to investigate further, and I discovered multiple versions of the text—some with separate ritual sections, others with independently circulating ritual manuals (vīdhis). The Chinese canon preserved some of these, as did the Tibetan canon, while the Dunhuang manuscript represented yet another variant.

This realization led to a major breakthrough: I began to see that ritual manuals had a life of their own, distinct from the canonical scriptures. Using the Taishō Tripiṭaka, I traced the emergence of ritual manuals, finding that they first appeared alongside dhāraṇī sūtras in the second half of the fifth century and proliferated in the sixth and seventh centuries.

Surprisingly, I found no evidence of Buddhist ritual manuals before this period. This was a revolutionary moment for me—I realized that an entire genre, central to contemporary Buddhist practice, had emerged relatively late in Buddhist history.

Ritual Manuals and the Proto-Tantric Debate

This finding intersected with a longstanding scholarly debate about whether dhāraṇī sūtras were proto-tantric. Scholars like Michel Strickmann argued that they were, while others, such as Robert Sharf, disagreed.

I concluded that dhāraṇī sūtras themselves were not tantric but rather Mahāyāna texts. However, the ritual manuals associated with them were proto-tantric. These manuals became a kind of “literary Petri dish,” fostering experimentation, localization, and innovation in Buddhist ritual practice.

What made these ritual manuals so flexible was their non-canonical status. Unlike scriptures deemed the word of the Buddha, these were human-authored texts that practitioners personalized with notes, additions, and modifications. Today, we can still see this practice in Tibetan Buddhism, where individuals compile personalized collections of prayers and instructions.

Yet, because they were seen as unimportant, these manuscripts were rarely preserved—except in rare cases like the Dunhuang collection, which offers a unique glimpse into this otherwise ephemeral tradition.

The Literary Qualities of Ritual Manuals

A turning point in my thinking came when Paula, a literature scholar, asked me what defined ritual manuals as a genre. Until then, I had approached them purely as practical guides. But her question forced me to consider their literary qualities.

Unlike Mahāyāna sūtras, which recount the Buddha’s teachings in a narrative framework, ritual manuals speak directly to the reader, instructing them in the imperative tense: “Place the offering here. Hold the beads in your right hand. Recite the mantra 21 times.” This direct address collapses the distance between text and practitioner, drawing the reader into the ritual itself.

With the rise of tantra, another shift occurred. The imagined world of the Buddha, once distant in Mahāyāna sūtras, merged with the practitioner’s experience. Instead of merely praying to a Buddha, practitioners imagined themselves as the Buddha at the center of the mandala.

This change is vividly illustrated in an eighth-century Tibetan commentary, which states that before drawing a physical mandala, the practitioner must first visualize the true mandala hovering above it. Here, the imagined world takes precedence over the physical.

The Evolution of Tantric Ritual and Poetic Language

A key feature of tantric ritual manuals is their use of poetry at crucial ritual moments. While early manuals were mostly prose, later tantric texts incorporated poetic passages, particularly during initiations and moments of transformation.

For example, in an initiation ritual, the master bestows symbolic objects upon the initiate while reciting poetic verses. This poetic register heightens the ritual’s significance, marking it as a moment of spiritual transformation.

By the ninth and tenth centuries, entire tantric ritual manuals were composed in verse, blurring the lines between human and Buddha-authored texts. These poetic passages, rich in metaphor and imagery, were designed to induce visionary experiences in the practitioner.

Conclusion

The developments I have traced in ritual manuals culminated in the late eighth and ninth centuries with the rise of esoteric initiations, the fourth empowerment, and the direct transmission of awakening through poetic or symbolic gestures—hallmarks of later tantric Buddhism.

While I have limited my argument to the evolution of ritual manuals, it is tempting to see a connection between these literary developments and the emergence of direct transmission methods in traditions like Dzogchen and Zen. By the end of the eighth century, the transmission of awakening was no longer solely a doctrinal process but an experiential one, facilitated through poetic, symbolic, and ritual means.

Thank you.