This piece follows up on my previous essay, “Tantric Deception: Black Magic and Power in Tibetan Buddhism,” which explored Solomon FitzHerbert’s study of tantric statecraft and the normalization of ritual violence in seventeenth-century Tibet. In this post, I turn to an even more revealing feature of FitzHerbert’s findings: the Fifth Dalai Lama’s own moral reasoning about ritual killing.

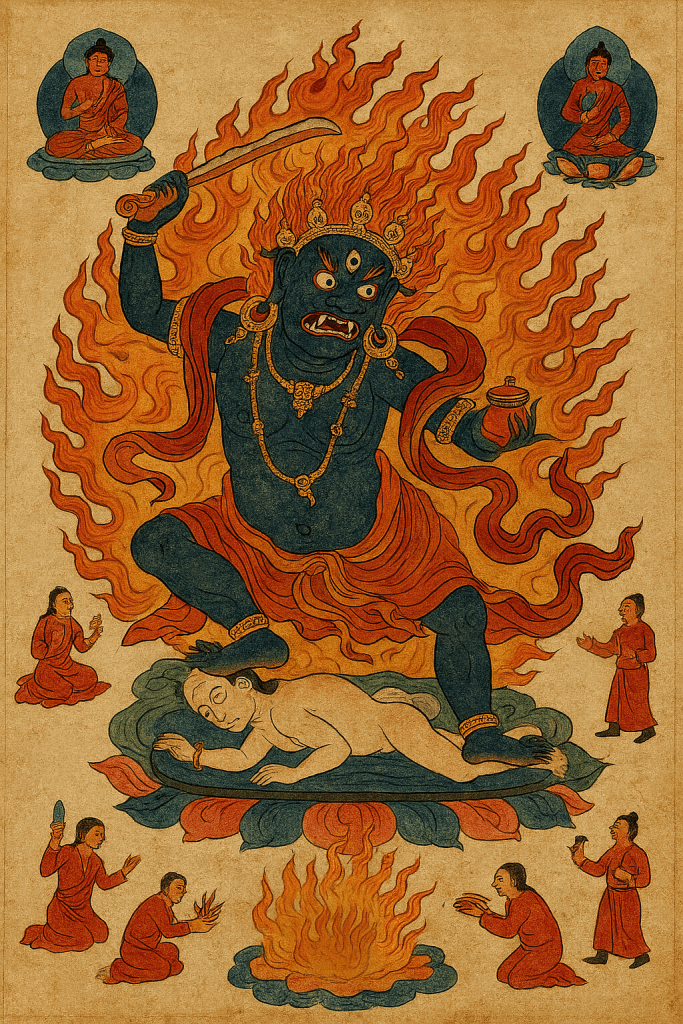

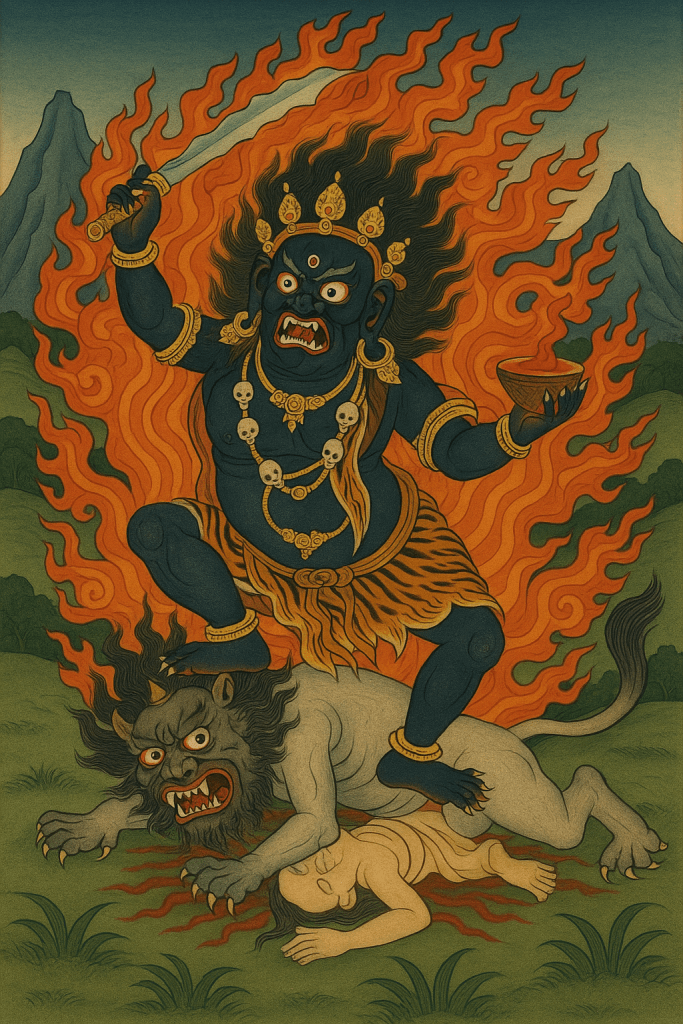

In his autobiography, the Fifth Dalai Lama confronts the criticism that tantric rituals of destruction should not be directed “against ordinary people.” His response is stunning in its candor: “We do not need to be ashamed of this,” he writes, “as it is taught in the Tantras.”¹ He goes further, citing the eight kinds of spirits who “fiercely execute the punishment” on behalf of the enlightened adept.²

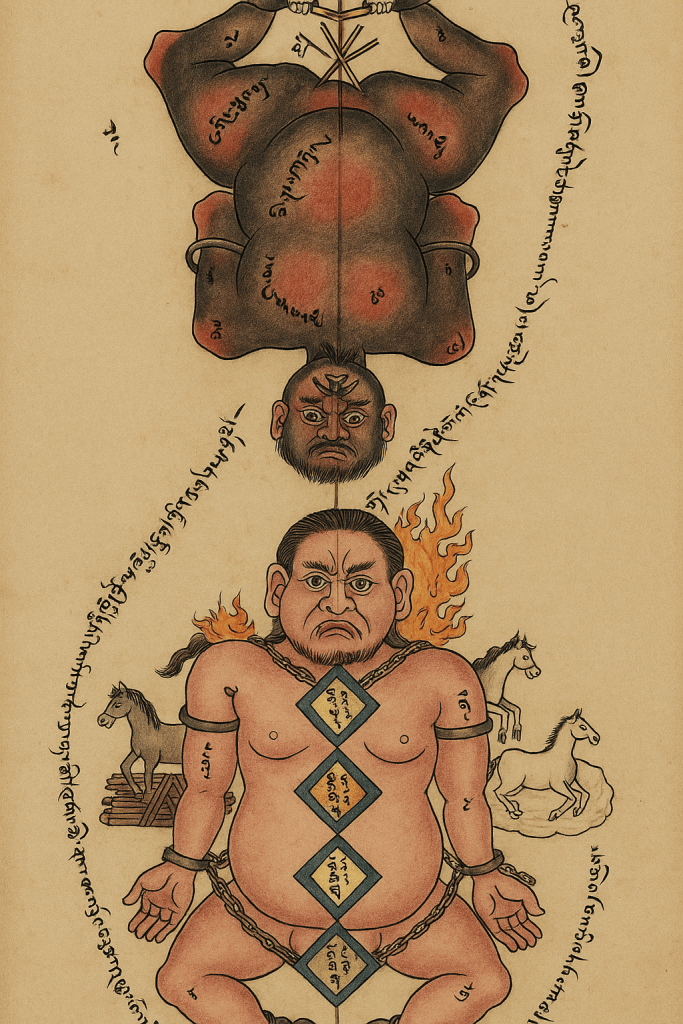

Here the Great Fifth is not apologizing for violence; he is codifying it. FitzHerbert explains that the Dalai Lama invokes a moral category known as the ten fields of liberation (sgrol ba’i zhing bcu), a rubric for identifying the kinds of people whose killing can be ritually justified in tantric Buddhism.³ These include those who “cause harm to the Buddhist religion,” “bring dishonour to the Three Jewels,” “endanger the life of the guru,” “slander the Mahāyāna,” “sow discord among the vajra community,” “prevent others from attaining siddhi,” or “pervert views concerning karma and its retribution.”⁴

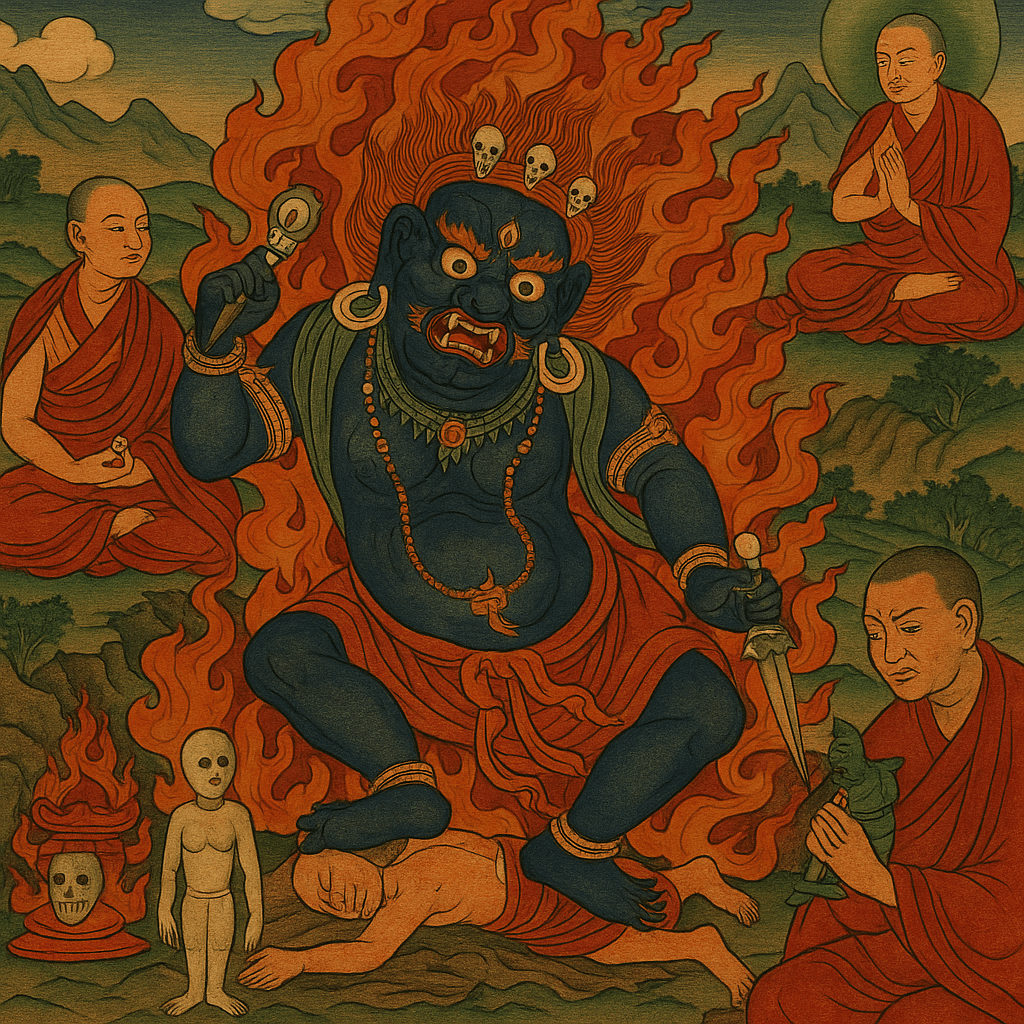

In other words, violence against the enemies of the dharma was not merely tolerated; it was systematized. The moral categories of Buddhist tantra aligned precisely with the ideological boundaries of religious loyalty. To kill an “enemy of the faith” was to enact liberation through wrathful compassion, a punitive act performed in the name of spiritual duty. In this context, the term liberation does not refer to enlightenment but serves as tantric code for killing.

The crucial question, then, is this: who decides who counts as an enemy of the dharma? It is the guru, a figure endowed with godlike authority, who makes that determination and authorizes the strike, much as a mafia boss sanctions a hit within his own organization.

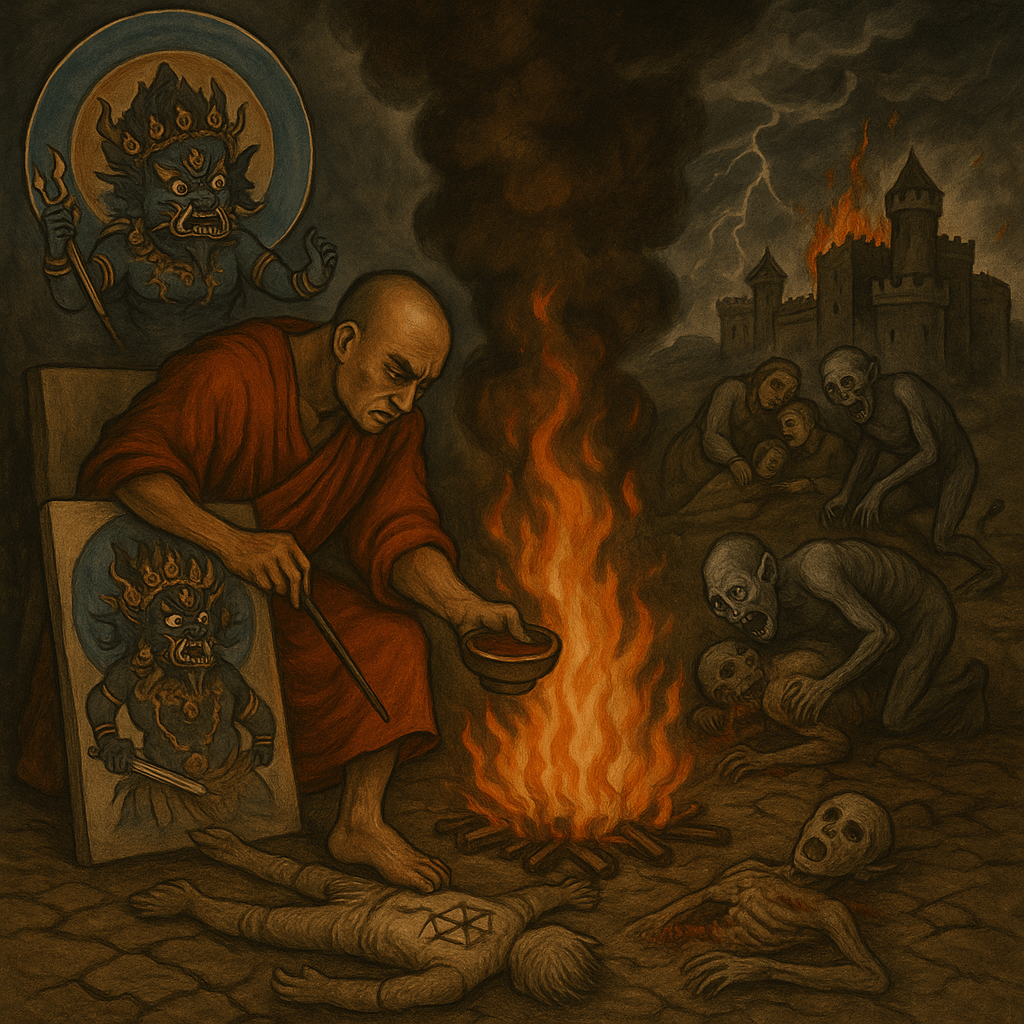

Such ideas did not remain abstract. As FitzHerbert shows elsewhere, the Dalai Lama’s government ritualized the deployment of these doctrines in warfare and political suppression.⁵ What we see in these passages is the theological backbone of that policy: a cosmological logic that made violence both righteous and karmically justified.

When the “Fields of Liberation” Become Personal

The ethical implications of this doctrine extend far beyond the seventeenth century. Its structure, dividing the world between defenders and destroyers of the dharma, still echoes in the tantric imagination today. Within closed guru/disciple networks, where authority is absolute and ritual power is personalized, this logic can turn inwards toward vulnerable disciples.

When a teacher is accused of abuse–sexual, financial, or psychological–some may interpret criticism of that teacher as slander of the Mahāyāna or harm to the guru, two of the very offenses listed in the ten fields of liberation. Under this view, the accuser becomes a threat to the vajra community itself. The rhetoric of “vajra hell,” karmic downfall, or spiritual ruin can be mobilized as a form of punishment.

Even when no public or obvious ritual of destruction is performed, the doctrinal framework legitimizing wrathful retribution remains intact and the teacher may privately extract revenge. A teacher who sees himself as an accomplished tantric adept may claim to act from “enlightened wrath.” Certainly he convinces himself that is the case. He may claim his retribution is not from malice but from a compassion that destroys obscurations and seeks to protect his community from dissenters. In this way, spiritual authority can blur into coercion, and the old metaphysics of tantric punishment can be redeployed against dissenting students.

Thus, the problem is not simply historical. It lies in a theological grammar that still allows destructive acts to be reframed as enlightened means. When criticism is recast as “slander of the dharma,” and when the guru’s person is identified with the deity itself, retaliation can be justified as upholding the sacred order.

Facing the Doctrine Honestly

When Western seekers encounter Tibetan Buddhism, we are often presented with an image of serene compassion, untainted by coercion or cruelty. Yet the Fifth Dalai Lama himself dismantles that illusion. He writes without hesitation that violent tantric rites are legitimate instruments of enlightened rule. The “theatre state” of seventeenth-century Tibet was the political expression of doctrines like the ten fields of liberation.

If the tradition is to be understood honestly, these passages should be part of an open and very public conversation. The Fifth Dalai Lama’s own words make clear that within tantric ethics, destruction is allowed, and killing can be framed as an act of perverted compassion. The challenge for modern practitioners and scholars alike is to recognize how this same moral architecture can exist whenever authority claims transcendence from accountability.

Footnotes

- Solomon G. FitzHerbert, “The Fifth Dalai Lama and the Tantric Politics of State Formation in Seventeenth-Century Tibet,” Arts Asiatiques 27 (2018): 88.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 89.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 74–83.