Shape-shifting has long been a recurring theme in mystical traditions across the world, appearing in shamanic practices, tantric rituals, and folklore. In Tibetan Buddhism, the Chakrasamvara Tantra contains instructions for shape-shifting, particularly into animals such as hawks and eagles. The presence of these spells in a sacred text raises an intriguing question: where do these siddhis (spiritual powers) truly originate from? Are they manifestations of enlightenment, or do they come at a cost, placing the practitioner in debt to unseen forces?

Shape-Shifting in the Cakrasamvara Tantra

The Cakrasamvara Tantra is one of the most esoteric and influential texts within the Anuttarayoga (highest yoga) class of Tantric Buddhism. Among its many rituals, it contains precise instructions for practitioners to take on non-human forms, including that of a bird. David Gray, in his translation and commentary on the text, notes that these shape-shifting spells are not mere metaphors but were understood as actual yogic attainments.

The text outlines multiple methods for transformation. One passage describes a ritual in which a practitioner can enchant a cord made from the sinew or hair of an animal and bind it around their neck to assume that animal’s form. This includes birds such as hawks, owls, and vultures, as well as larger quadrupeds (Cakrasamvara Tantra, Chapter XLVII, p. 363). Another section states that by consuming or even touching an enchanted substance, the yogin may take on a divine or animal form (Cakrasamvara Tantra, Chapter XLIX, p. 369). These instructions suggest that shape-shifting was considered a real and attainable siddhi for advanced practitioners.

In Vajrayana, these extraordinary abilities, known as siddhis, are divided into two categories:

- Mundane siddhis (laukika siddhis), which include powers such as flight, invisibility, and shape-shifting.

- Supreme siddhis (lokottara siddhis), which refer to enlightenment itself.

While the latter is the ultimate goal of practice, the existence of spells for mundane abilities suggests that some practitioners were actively seeking, and attaining, more earthly, supernatural powers.

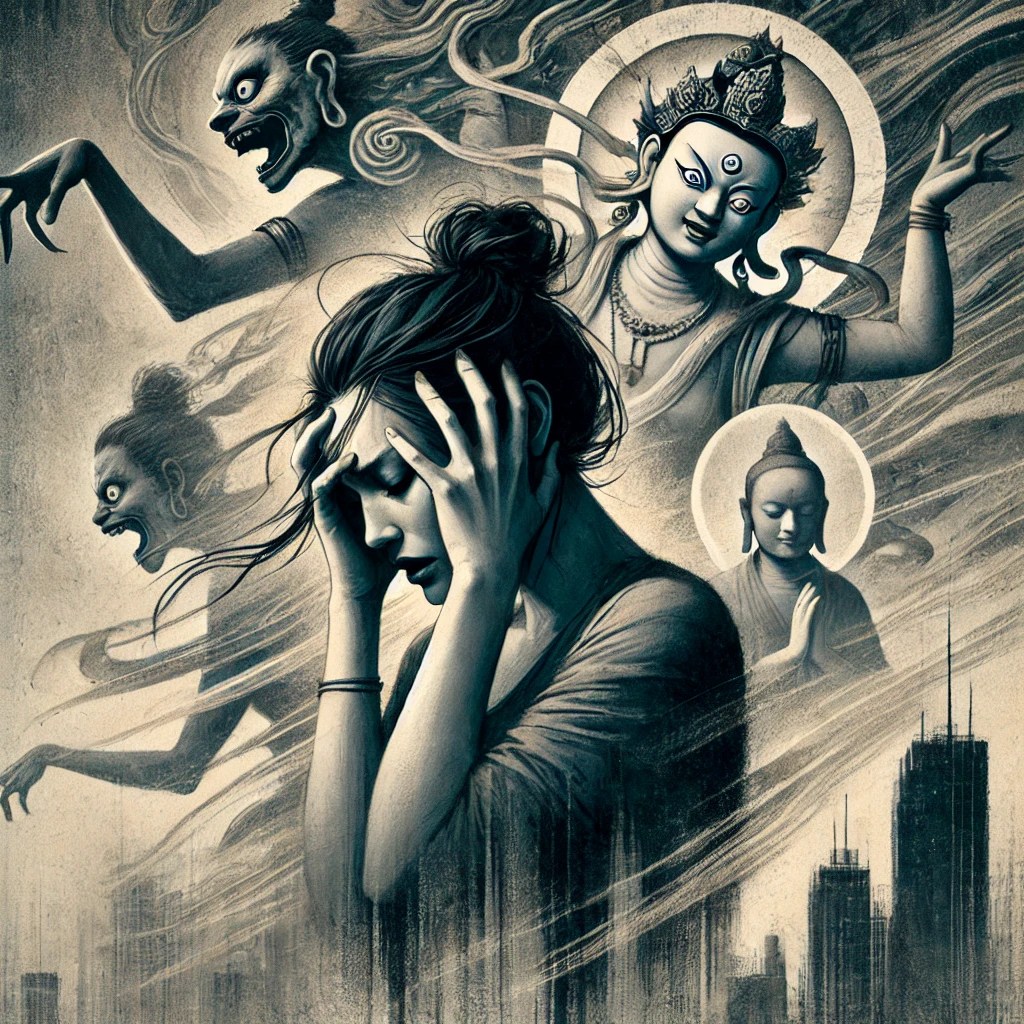

But why would a Buddhist tantra contain shape-shifting spells? The standard response is that these abilities help advanced practitioners aid sentient beings and overcome obstacles. However, if the goal were purely benevolent, why does the very same tantra contain spells for harming, controlling, and even destroying sentient beings? The presence of violent and coercive rituals alongside shape-shifting practices suggests that acquiring such siddhis was not solely about compassion or enlightenment. Instead, these abilities may have served more ambiguous or self-serving purposes, whether for power, domination, and even destruction. Moreover, history is filled with accounts of people acquiring mystical abilities at a hidden cost, often through pacts with forces beyond their ultimate control or comprehension. If a yogin can assume the form of an animal, what else might they be gaining or losing in the process?

Debt to the Unseen: Shape-Shifting and Supernatural Pacts

The idea that magical transformations require spiritual debt is not unique to Tantra. Across cultures, shape-shifting often comes with hidden agreements between the practitioner and demonic entities.

- Shamanism and Possession: In many indigenous traditions, a shaman does not shape-shift alone but must first enter a trance state, often facilitated by spirits or tutelary deities. This raises the question, when a shaman transforms into an animal, are they truly in control, or is something else working through them?

- Vampirism and the Undead Pact: The myth of the vampire is closely related to shape-shifting, with folklore describing their ability to turn into bats, wolves, or mist. Yet, vampires are universally depicted as cursed beings who exist by taking the life force of others. Their transformations are not self-generated but come as a consequence of an external force, a dark exchange that binds them to an unnatural state.

- Faustian Bargains in Occult Traditions: From medieval grimoires to modern occultism, the idea persists that those who seek supernatural abilities must often enter into a contract with demonic non-human entities. The magician gains knowledge or power but loses something in return, whether it be autonomy or a portion of their soul.

Could the siddhis described in tantric texts function similarly? If shape-shifting is possible, does it occur through the practitioner’s own spiritual mastery, or is it facilitated by a demonic force to which they become indebted?

The Cost of Siddhis: Are They Truly Benevolent?

Tantric Buddhism teaches that mundane siddhis should never be sought for their own sake. In the Hevajra Tantra, a text closely related to Chakrasamvara, the practitioner is warned that seeking supernatural abilities out of attachment can lead to ruin. Some Buddhist teachers even caution that siddhis can become obstacles on the path to liberation, enticing practitioners away from true spiritual realization.

If shape-shifting and similar siddhis are real, should they be seen as gifts of an awakened mind or as evidence of hidden transactions with demonic forces? If the latter, what do these forces ultimately seek in return?

For those who have witnessed such transformations firsthand, the question remains: What is really behind them?

[1] Gray, David B. (2007). The Cakrasamvara Tantra (The Discourse of Śrī Heruka): A Study and Annotated Translation. New York: American Institute of Buddhist Studies at Columbia University. ISBN: 978-0975373460. See Chapter XLVII, p. 363, and Chapter XLIX, p. 369 for descriptions of shape-shifting methods.