The following is based on Aleksandra Wenta’s article “Tantric Ritual and Conflict in Tibetan Buddhist Society: The Cult of Yamāntaka” (2022).

Public perception paints Buddhism as the ultimate religion of compassion. The Dalai Lama’s cheerful smile and monks chanting in maroon robes conjure images of peace in the Western imagination. But the historical record tells quite another story, one most Buddhist institutions would prefer to bury. Violent ritual has always had a place in Tibetan Buddhist practice, and the cult of the wrathful deity Yamantaka is one of the clearest examples.

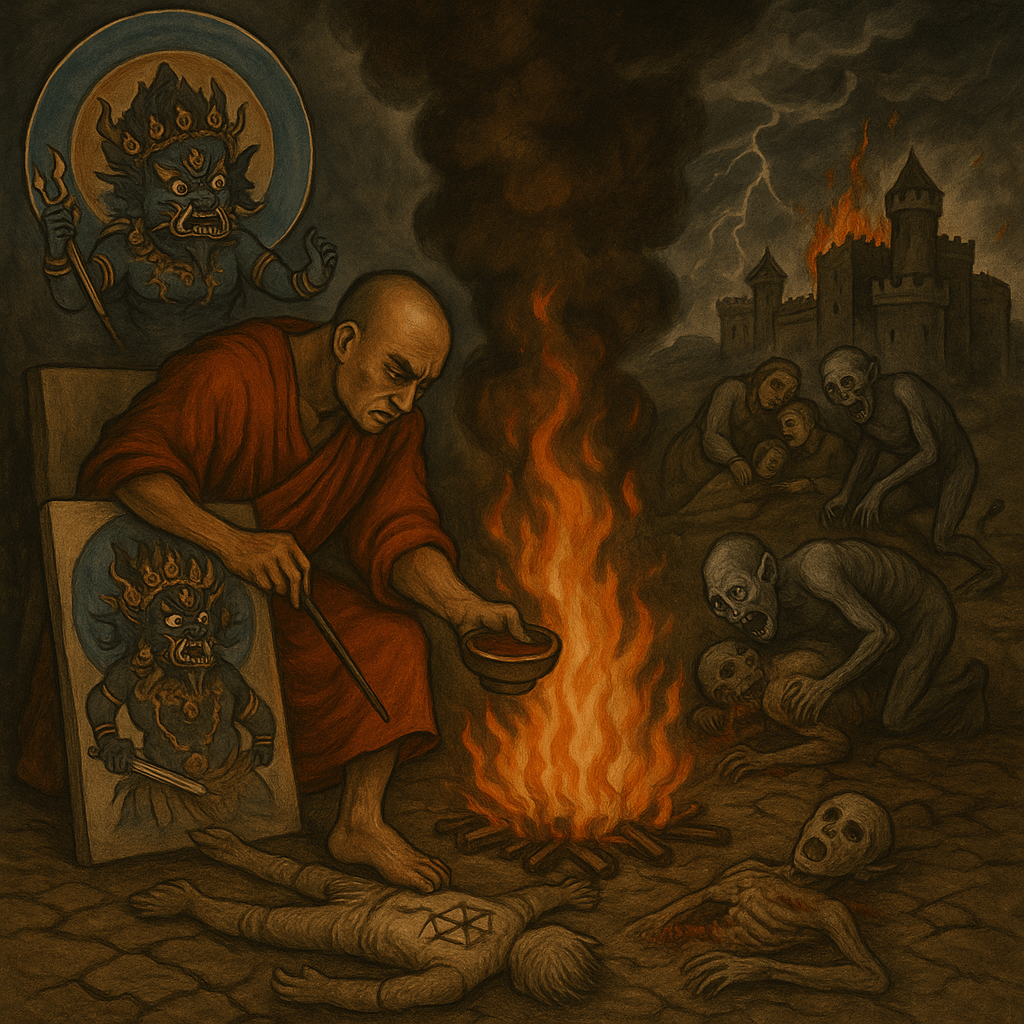

The Deity of Destruction

Yamantaka, whose name means “Ender of Death,” is no serene Buddha. In tantric lore he is a ferocious, multi-headed, weapon-wielding deity invoked to annihilate enemies. These enemies might be inner demons in metaphor, but in many cases they were very real human targets. As Wenta’s research shows, Tibetan Buddhist ritual specialists used Yamantaka rites as deliberate acts of destruction, both spiritual and physical.

Politics and Ritual Warfare

The historical examples are difficult to dismiss. In the ninth century, the Buddhist master Gnubs chen Sangs rgyas yeshes allegedly used Yamantaka magic against King Lang Darma, a ruler seen as hostile to the Dharma. Centuries later, during the political struggles of the seventeenth century, the Fifth Dalai Lama employed Yamantaka rituals to consolidate power over rival factions. These were not fringe experiments, but state-linked religious acts intended to remove opponents.

The reach of these rites went beyond Tibet. The Manchu Qianlong emperor adopted Yamantaka worship to project legitimacy over his subjects, while Mongolian and Japanese traditions incorporated similar ritual violence into their own religious-political frameworks.

Violent Compassion as Justification

Practitioners did not see these rites as morally corrupt. They justified them through the doctrine of “violent compassion,” the belief that killing or harming could liberate an enemy from a worse rebirth. Wenta notes that tantric philosophy, particularly the doctrine of emptiness, was used to argue that concepts like killer or victim do not ultimately exist. In this logic, an enlightened being could commit an act of violence without accruing negative karma.

Ritualized Destruction

From the Mañjuśriyamūlakalpa’s “Ritual Against the Wicked Kings” comes one of the most explicit and brutal examples. The text instructs the practitioner to paint Yamantaka in terrifying form, then perform fire offerings of human blood, flesh, and powdered bone mixed with poisons and toxic plants to unleash plague, famine, storms, and demonic infestations upon the target. The king’s family is to die in sequence: son on the first day, wife and ministers on the second, the king himself on the third, while his court is overrun by flesh-eating spirits and his land struck by drought, fire from the sky, rockfall, and invasion. A human effigy bearing the victim’s birth star in cremation-ground charcoal is trampled during mantric recitation so the enemy dies, goes mad, or is devoured by demons. This is ritualized destruction in its most literal, calculated form.

One section of the same text reads like a manual for calculated devastation. The practitioner is instructed to heap human blood, flesh, powdered bone, poisons, and the roots of deadly plants onto a ritual fire in front of the painted deity. After 1008 offerings, not only is the enemy destroyed, but their family, ministers, and allies are swept away as well. The text promises droughts, plagues, famine, and storms, even fire and rocks falling from the sky, while demonic forces overrun the victim’s court. In some variations, a single datura root is enough to drive the target insane, or a few spoonfuls of spiced offerings can induce fatal fevers within days.

The text also states, “If he wants to kill someone, then having made a puppet (kṛtiṃ) he should write a name: the deity name or a nakṣatra (‘asterism under which the target was born’) using a charcoal of the cremation ground, which should be placed on the ground in front of the paṭa. Standing on [the puppet’s] head with his foot, he should be in a wrathful state, and do the recitation. He (the king) will become overpowered by a major disease, or he will die on the spot. That lord of men will be seized by piercing pains for no apparent reason, or he will be killed by an animal, or he will become crippled. He will be eaten by fierce rākṣasas, and various impure beings that have arisen from non-human birth (kravyādin), pūtanas, piśācas, pretas and the mothers, or he will be killed immediately by his own attendants.” 1

Conflict Inside the Tradition

Even within Tibetan Buddhism, the legitimacy of destructive rituals such as these was contested. Some figures, such as Rwa lo tsā ba, became famous for their wrathful practices but were denounced by peers as frauds or heretics. Reformers like Yeshes ’od tried to curtail the most extreme acts, replacing “live liberation” killings with symbolic substitutes like effigy destruction. But these reforms did not erase the underlying acceptance of ritual violence; they only tamed it for public consumption.

Another Piece of the Puzzle

Wenta’s work adds yet another piece of hard evidence to the growing pile that Tibetan Buddhism has long included practices designed to harm or destroy. These rituals were not simply metaphorical, and they were not limited to obscure sects. They were woven into the political and religious fabric of Tibet and beyond.

For those willing to look past Tibetan Buddhism’s carefully crafted PR image, the cult of Yamantaka exposes a reality in which the language of compassion hid a persistent undercurrent of deliberate harm.

Footnotes

1) Aleksandra Wenta, Tantric Ritual and Conflict in Tibetan Buddhist Society: The Cult of Yamāntaka, in Esimoncini, 19 Wenta CHIUSO, available at https://tibetanbuddhistencyclopedia.com/en/images/0/0b/Esimoncini%2C%2B19_Wenta_CHIUSO.pdf. ↩