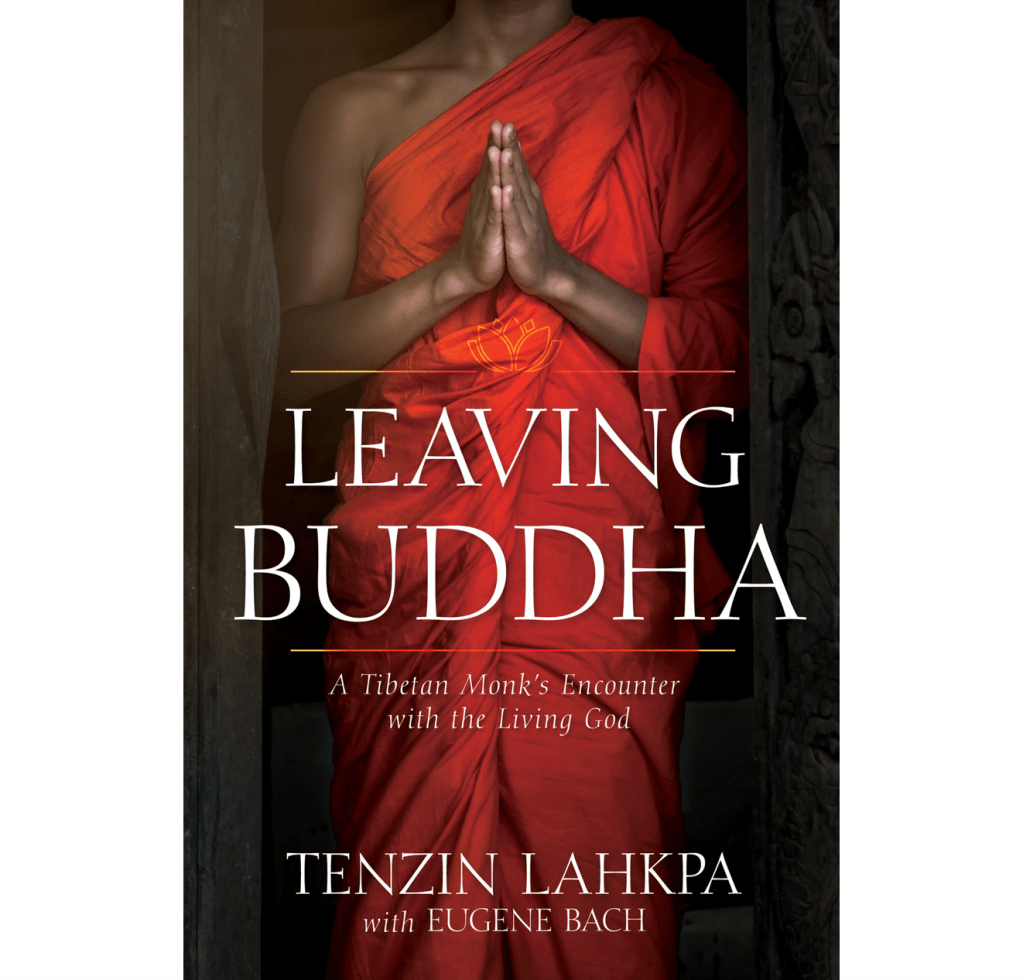

When Tenzin Lahkpa is fifteen years old, his parents give him over to a local temple in Tibet as an offering. Unable to change his fate, he wholeheartedly embraces his life as a monk and begins a quest for full enlightenment through the teachings of Buddhism. From his local monastery to the famed Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet, he learns deep mysteries of Tibetan Buddhism. Yearning to study with the current Dalai Lama, he eventually escapes from China by means of an excruciating, two-thousand-mile, secret trek over the Himalayas—barefoot, with no extra gear, changes of clothing, or money. His dream is realized when he finally sits under the Dalai Lama himself. But his desire to go deeper only grows, leading him to unexpected conclusions…. Follow the fascinating, never-before-told, true story of what causes a highly dedicated Tibetan Buddhist monk to make the radical decision to walk away from the teachings of Buddha and leave his monastery to follow Jesus Christ. Discover the reasons other monks want him dead before he can share his story with others. Leaving Buddha dares to expose the mysterious world of Tibetan Buddhism, with its layered teachings, intricate practices, and troubling secrets. Ultimately, it tells a moving story about the search for truth, the path of enlightenment, and how no one is beyond the reach of a loving God. This gripping narrative will resonate with people from all backgrounds and nations.

“I had learned about the night cries earlier that day. Several of us monks-in-training had gone down to a nearby stream to bathe and swim. One of the boys whom I knew well and who was much younger than I took off his robe. I was shocked when I noticed marks across his back that looked like scars from being whipped by a leather strap. “What happened to him?” I asked in general. Gyatso looked in the direction where I was looking to see who I was referring to. Then, he looked at me and said, “Oh, that is Gantdo Lama.” I didn’t need to ask another question. I knew exactly what had happened. Gyatso was not saying that the boy’s name was Gantdo Lama; he was saying that what had happened to him had been done by Gantdo Lama.

Gantdo Lama was one of the meanest and most violent monks in the monastery. Everyone was afraid of him. He beat his disciples on a regular basis, and he was always yelling and screaming at others. One time, he damaged part of an altar when he got into a fight with one of the worshippers who had come into the monastery, accidentally gotten in his way, and not shown him the proper respect. “Poor guy,” Gyatso said about the boy. “He tried to escape but was caught and beaten by Gantdo Lama.” “Why did he try to escape?” I asked. “Shhhhh…keep it down,” Gyatso said as he looked around to see if anyone else was listening. “You don’t know?” I shook my head no. “You really do not know?” he asked again in a lower but more incredulous voice. “Because he is Gantdo’s new dakini.”

A dakini is often the term for someone who is used for sexual pleasure by Tibetan lamas. I had heard my brothers use the word before, but I hadn’t heard many people use it since I had been living at the temple. “You know, you should count yourself lucky that you have never had to deal with Gantdo Lama. That guy turns all of his disciples into dakinis during their first year of service.” Many of the lamas at our temple had secret wives that they would sneak out to meet, while others had dakinis, but I had never imagined they would use the boy monks for this. We both looked over again at the wounds on the back of the young boy. They were hard to look at. “Man, these lamas,” Gyatso said. “They think they can do whatever they want and get away with it. They walk around like they are so holy and enlightened, but so many of them are child rapists.”

Gyatso was not wrong. The lamas are powerful individuals, and their power goes largely unchecked because they answer to no one outside of ecclesiastical authority. The Tibetan temples deal with sexual fantasies as they see fit and answer to no one on the outside about their practices. “The teachings here really blur the lines, you know? I mean, the first thing that they do is tell you that there is no such thing as good and evil. They remove the boundaries between what you think is good and what you think is bad. After a while, everything is relative. From day one, we are taught that pain is the result of desire, and enlightenment is giving yourself over to where boundaries no longer exist. Oh yeah, they love that. That way, when you feel the pain of them raping you, it is your problem—not theirs!” I couldn’t tell because of the sunlight glistening on the water, but it almost looked as if tears were welling up in Gyatso’s eyes. I stayed silent. I was listening, but I waded into the water and slowly swished it a little with my hands. I thought that by pretending not to fully notice his tears and painful words, it might lessen his pain.

“If a victim is in pain, it is the result of their lack of desire to serve,” he continued. “A monk must serve his master.” Gyatso’s words were angry. There was nothing I could say or do to help him, so I continued to pretend not to be too invested. “My parents never would have left me here if they had known that this was going on,” he said. “I should never have taken the oath of that stupid samaya!” I froze. Samaya is the most sacred bond between a disciple and teacher and can never be broken. When I entered into the agreement with Tashi Lama, it was a sacred moment in which I promised to give him my speech, mind, and body. Once you enter into the samaya, you can never leave unless you want to experience eternal torment. There are fourteen ways that the samaya can be broken and all of them are very serious. According to the teachings of Tibetan Buddhism, a few of the ways to break the samaya are disrespecting your master, disobeying the words of the Buddhas, or criticizing the teachings of the Buddhas. The worst is revealing the secrets of Buddhism to those who are unworthy. But not taking the secret oath of the samaya was blasphemous, and breaking the oath would earn a monk the most torturous part of hell. In Tibetan Buddhism, there are eighteen different levels of hell. Level eighteen is the most painful and excruciating—and it is reserved for people who break the samaya. That night, as I lay on my mat and heard the cries of the young boy, I could not help but think about Gyatso’s words. Surely his parents would never have brought him to the temple to live the life of a monk if they had known what happened to many of the young boys after dark. I am certain that my parents did not know. The last thing we thought anyone would see at the monastery was sex. It never crossed our minds. According to the teachings of Tashi Lama, I was not to engage in any sexual activities. This was one of the first teachings I received, and it was pounded into my head over and over again. Having sex of any kind was a serious monastic transgression that was ranked among theft, murder, and lying. Even masturbation was considered to be an offense that would get a monk kicked out of the monastery. The prohibition had seemed pretty clear to me at the time, but it was not so clear anymore. The very thing that I had been told was wrong was being practiced by one of the senior teachers, and there was nothing I could do about it. Tashi Lama’s teachings were not as insightful as they had been when I first arrived—they were getting more and more predictable—but at least he wasn’t abusive. Lying there in the night and listening to the cries of Gantdo’s disciple, I realized that this was one of the secrets that I would never be able to share with those outside of the temple. Sharing the secrets was a damning offense that would send me to level eighteen of hell.”

Lahkpa, Tenzin; Bach, Eugene. Leaving Buddha . Whitaker House. Kindle Edition. Available on Amazon.

Worth reading

LikeLike